Luo Xiao: Elevating Survival into an Art of Living

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Luo Xiao: Elevating Survival into an Art of Living

Born in 1986, Luo Xiao possesses a composure beyond his years, as if the temperament of an artist flows inherently through his veins. At 16, he apprenticed under Guo Wenlian, a professor at Jingdezhen Ceramic University, embarking on a path that merged theoretical study with hands-on ceramic craftsmanship.

Three years of rigorous training laid a solid foundation for his future independent design brand, “Xiang Shang.”

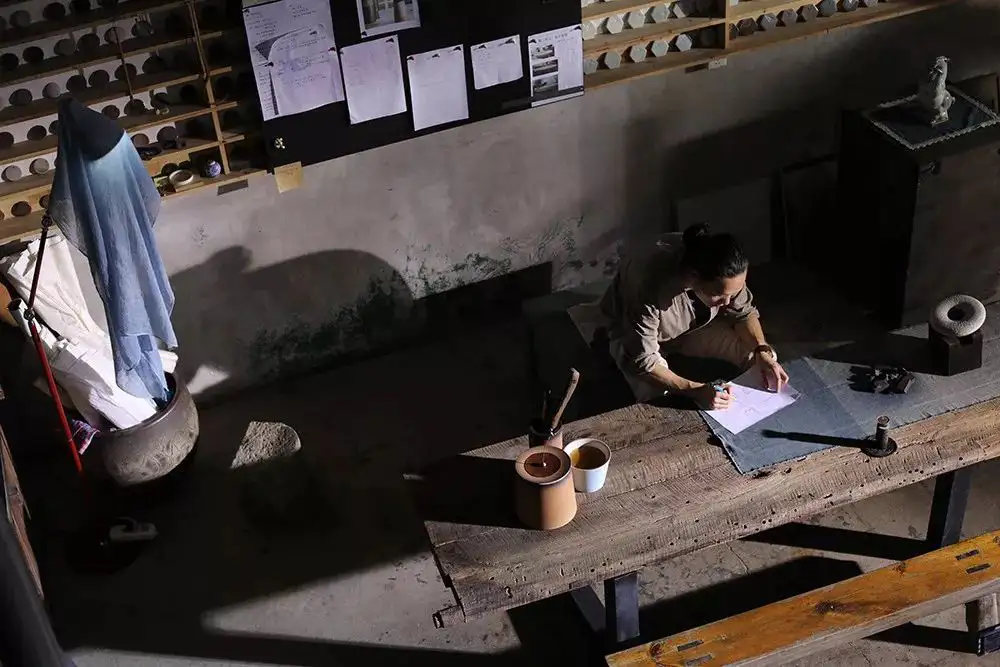

In Sanbao Village, not far from the ancient kiln sites of Hutian, a narrow, unmarked dirt path winds upward past a succulent greenhouse to Luo Xiao’s Xiang Shang Studio.

Once a derelict factory, the site was overgrown with weeds and inaccessible when Luo Xiao first arrived. He and his brother rolled up their sleeves to transform it: preserving the old windows and yellow brick walls, painting the interiors green, and repairing the wooden roof while leaving a skylight for sunlight to stream in.

The courtyard was redesigned too—the towering trees remained, but now accompanied by outdoor dining decor and a Dogo Argentino that roams the village. On the slope, Luo Xiao built a cozy guesthouse for visiting friends. Over time, the studio “filled up”: workout rings, a dramatic test-tile wall, works crowding the tables…

Here, they throw pots, glaze, play music, host weddings, and watch the World Cup under the stars.

Amid this fusion of life and nature, Luo Xiao ponders boundless ideas. His thick sketchbooks are crammed with designs—some meticulously detailed with measurements, others just fleeting sketches with scribbled notes. A few evolve through repeated refinement into rational products that return to everyday life.

For many, survival is a heavy burden. But for Luo Xiao, it’s a cycle: drawing from life, reinterpreting it through thought and design, and reintegrating it as poetry—an elevated way of living.

01 The Last Apprentice

With long hair tied back and a plain T-shirt, Luo Xiao resembles a cutting-edge design school graduate. Yet behind his sleek creations lies the discipline of Jingdezhen’s most traditional apprenticeship.

In 2002, the 16-year-old Luo Xiao boarded an overnight train from Nanchang to Jingdezhen after high school. Arriving in the pitch-dark, crumbling streets, he felt uneasy as his introducer dumped his bags at Professor Guo’s home.

“Genuine, solitary, slow to bloom”—these are the words Luo Xiao uses for himself.

His introversion sharpened his senses. He recalls waking the next morning to autumn sunlight piercing his room’s window, the anxiety melting away. The immersive craft culture, unfamiliar yet addictive, felt like stepping into a new world.

He met Professor Guo Wenlian of Jingdezhen Ceramic University.

While peers attended college, Luo Xiao chose apprenticeship—becoming what he calls “Jingdezhen’s last true disciple.” Living in his master’s home for two and a half years, he endured strict training blending traditional ceramics with academic art fundamentals, covering everything from daily chores to pottery-making.

“It felt like a young monk studying under an old Zen master.”

Starting from zero, he practiced sketching daily in the garden, reviewing his work with Guo. Among the master’s disciples, Luo Xiao wasn’t the most gifted but was the most diligent—rising earliest, sleeping latest.

Beyond study, he handled household tasks: cleaning, grocery prep, hauling goods. Acid rain from Jingdezhen’s industrial pollution meant weekly fish tank maintenance. These chores were inseparable from traditional apprenticeship.

Later, Luo Xiao assisted Guo in design research, liaising with factories and conducting glaze experiments. “My master’s rigor—in work and ceramic philosophy—shaped me profoundly. Those three years were beautiful because of his guidance. Leaving was necessary, though. I needed to test myself in the real world.”

▲ Luo Xiao’s works

Despite his master’s shelter, Luo Xiao craved broader horizons and eventually set out on his own.

02 Experimenting with Color Glazes

When Luo Xiao first moved his studio to Sanbao, there was no path up the hill—he and his brother carved one themselves. Their chosen focus, color glazes, was a high-barrier technique demanding endless trials, seldom pursued by the young.

In Jingdezhen’s lexicon, color glazes are traditional. “One glaze on 18 test tiles, fired in different kiln spots, yields 18 hues—that’s the magic. Half human effort, half heaven’s will.” Luo Xiao was hooked.

Earlier, he’d worked at factories in design and management roles, even learning glassmaking. But when design was reduced to mere drafting, he quit.

Drawing on glaze experiments with Guo and factory experience, he plunged into color glaze research, aiming to modernize tradition for contemporary aesthetics.

▲ Color glaze series

In 2008, Zheng Yi’s Pottery Workshop launched the Loft Market to nurture young ceramists. Luo Xiao calls his early independence “sprouting.” Amid the market’s chaos, he observed, participated, and gradually found his voice.

From design to glaze formulation, he did it all.

Luo Xiao chose the toughest path: high-temperature color glazes. Unlike other ceramic arts, this demands relentless testing—thousands of trial tiles. Painstaking and dull, but his apprenticeship had prepared him.

Initially, he worked intuitively, rarely repeating designs. Like artists with “clean-freak” tendencies, each piece was unique.

He reveled in the process, even the suspense of kiln openings. Failures didn’t faze him—they bred surprises, like his accidental “bubble glaze.” At first, the lumpy texture repelled him, until he cracked a bubble to reveal unexpected colors.

Thus, he salvaged the “flaws” into new creations.

Kiln transformations conjured seascapes, volcanoes, galaxies—but these were no accidents. They emerged from countless attempts. His palette shifted from grays to vibrancy as life brightened. Every piece was an honest dialogue with clay.

His studio is a meticulous archive: shelves of jars hold semi-finished or “failed” works—diaries of his journey.

03 Utility Ware as Altruism

At markets, his “imperfect” pieces sold inexplicably well. Requests poured in: replicas, bulk orders. His first commission—600 handmade cups at 8 yuan each—meant sleepless weeks of trimming, drying, and glazing.

This pushed him toward standardization, a painful pivot.

Professor Guo noted in an interview: “Many pursue fame or profit in ceramics today. Luo Xiao’s choice—anonymous utility ware—is unglamorous. For a young artist to persist, handling everything from form to glaze alone, is rare. His grasp of ceramics is holistic.”

To focus on design, Luo Xiao recruited his brother.

“I was ‘tricked’ here,” laughs Luo Hua. “I had a comfortable life in Tonglu—great scenery, good pay. But his vision for a lifestyle brand blending color glazes with functional ware convinced me to join.”

▲ Left: Luo Xiao; Right: Luo Hua

In 2013, they launched Xiang Shang, creating wares that express ceramic’s vitality through the five elements (metal, wood, water, fire, earth) and the interplay of curves and angles.

Luo Xiao chose utility ware as an act of giving. His muse, Lucie Rie, once said: “Hands impart soul; let the work speak. No sentimentality, no theory—just serene beauty. Nothing needs overstatement, neither pots nor life.”

He too seeks soulful objects.

One incense holder subverts stability—its movable structure holds 31 sticks (one month’s worth), each burning for 15 minutes, inviting users to contemplate time.

Recently, Luo Xiao has evolved for Xiang Shang’s sake. Once a workaholic oblivious to anything beyond clay, he’d famously forget his wallet. Now a brand owner, he struggled to balance family, creativity, and business, veering into obsession or escape.

He’s learning to separate art from product, shifting from solo craft to structured production. Standardization is inevitable—products demand consistency in form, function, and beauty.

A trapezoidal cup took five years of tweaks. For an incense burner’s water reflection, he engineered a mixed-material base, down to the circuitry.

“Every functional form endures many mistakes before success.”

Avoidance, he realized, didn’t buy creative time—it bred inefficiency.

So he leans in. One evening, he played music at home. His daughter proposed a dance party. In the dim light, drinks in hand, the rhythm moved him—a rare moment of letting go. The next day, their bond felt deeper.

Now, family time fuels his work. “The essence of things lies in their nature,” he reflects. “What distinguishes people is perception.”

He hopes Xiang Shang inspires lifestyles, awakening fresh ways to feel alive.