Yu Yin: Leading the ‘Aged’ Yi Lin Tang into the Future

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Yu Yin: Leading the ‘Aged’ Yi Lin Tang into the Future

This year marks his seventh since taking over Yi Lin Tang. When he first became the young master, he bore fewer responsibilities, fewer shackles, and no worries or sense of mission.

But seven years later, after meeting many people and creating countless stories with them, he began to understand what he carried on his shoulders. Yi Lin Tang grew alongside him, and every step taught him the true meaning of inheritance.

In 2012, amid a tea-drinking trend, the tea ware market boomed, with sales and prices multiplying. Many seized the opportunity to enter the industry. But twenty-year-old Yu Yin chose to turn away at this very moment. He decided to close the ceramic brand store he’d operated in Shanghai for four years.

This store had been set up with his father’s help.

In his freshman year, while studying art design in Shanghai, he wanted to drop out and start a ceramic business. His father fell silent but ultimately didn’t stop him.

Calmly, his father took Yu Yin to visit friends in the tea ware industry, negotiating deals one by one. In 2009, they secured the national distributorship for Xiaoya, a renowned Jingdezhen brand, and opened the store in Shanghai. Within three years, Yu Yin raised the price of a teapot from 300 yuan to 30,000 yuan. Continuing the business would have been a steady source of income.

But at this very moment, Yu Yin shut the store. He no longer wanted to sell others’ brands—he wanted to return to Jingdezhen and revive his family’s brand, Yi Lin Tang. His usually open-minded father wasn’t pleased; instead, he firmly opposed the idea.

01 The Yi Lin Tang Legacy Isn’t Easy to Inherit

Yi Lin Tang was founded by Yu Yin’s grandfather in 1953 and has a 64-year history. In the 1980s, Yu Yin’s father took over. Both generations devoted themselves to mastering famille-rose porcelain replication, earning high repute in the industry.

Yu Yin came to Fanjiajing—Jingdezhen’s antique porcelain hub—at the age of five. Back then, his family’s five-story building housed a display area on the first floor, living quarters on the second, and ceramic workshops on the third to fifth floors.

In his memories, the house buzzed with Southeast Asian clients who often visited. Upstairs, uncles and aunts bent over porcelain, painting diligently. He often saw his father’s back, hunched over research in solitude.

In 2003, while studying Republic-era enamel colors, his father spent days tinkering with a small scale in his room, testing samples. Even during SARS and the financial crisis, when the economy slumped, their products always sold. As he grew older, Yu Yin traveled to Taiwan with his family to meet his father’s old friends. When they brought out treasured Yi Lin Tang pieces, the conversations flowed warmly.

Though born into a ceramic family, Yu Yin wasn’t particularly fond of porcelain. He took for granted the quality of his elders’ work. His father, emotionally reserved, never explained much.

It wasn’t until he entered the ceramic business—before even turning eighteen, with his father handling the store’s装修 (renovation)—that he began to appreciate the craft. By the next year, he redesigned the store and revamped its inventory.

Dealing with ceramics meant interacting with many people. In Jingdezhen, artisans don’t care about wealth—they value your understanding of ceramics. As a dealer, Yu Yin had to offer suggestions, which required deep knowledge. The more he learned, the more he realized ceramics’ vastness. Looking back, ceramic development reflects the evolution of Chinese culture, art, and taste.

By 2010, an idea struck him: Our family’s craftsmanship is exceptional, and Yi Lin Tang has spanned three generations. If I can successfully market other Jingdezhen brands, why not our own?

But his father refused. For two years, Yu Yin pleaded, but his father remained unmoved.

His father had spent a lifetime mastering famille-rose porcelain. Like many Jingdezhen artisans, he didn’t want his descendants in the trade. Creating original famille-rose porcelain is agonizing—it involves technical communication, management, design, and R&D. It’s no easy task for a young person.

But twenty-year-old Yu Yin, bold and defiant, ignored these unseen hardships. He simply wanted to do what he believed was right.

After two years of futile struggle, he closed the store without further discussion and returned to Jingdezhen.

02 Becoming the Young Master: Two Years Living in the Shop

With no other choice, his father relented, letting Yu Yin take over Yi Lin Tang.

Starting in 2012, Yu Yin solemnly stamped “Yi Lin Tang” on the base of each piece, determined to create the world’s most beautiful famille-rose porcelain. But as his father predicted, hardship followed.

Yi Lin Tang’s two generations had focused on famille-rose research.

Famille-rose porcelain isn’t ancient.

In the late Kangxi era of the Qing Dynasty, artisans, inspired by enamel painting techniques, developed famille-rose (or “soft colors”)—a low-fired overglaze painting method. It peaked during the Yongzheng and Qianlong reigns.

The technique involves adding “glass white,” an opaque pigment that creates a soft, powdery effect, hence the name “famille-rose.”

His father assigned Yu Yin three master painters—specialists in flowers/birds, landscapes, and figures.

But Yu Yin was young. Though his father supported him, he couldn’t always guide him. Early on, communication issues arose with the masters.

“The setbacks were endless.”

At first, the masters dismissed him as a clueless kid. For instance, when a piece’s base yellowed due to smoke absorption, they claimed it was a desirable “Republic-era characteristic.”

Painters, paid per piece, resisted criticism. Skilled but proud, they only respected those who understood the craft. If Yu Yin gave uninformed advice, they’d humor him while privately dismissing him.

“My father’s reputation opened doors, but in conversations, he couldn’t speak for me. I had to learn everything myself—body shaping, glaze formulas, color development, painting techniques for landscapes, flora/fauna, and filling methods. Only then could I contribute meaningfully.”

He interacted with over a dozen specialized roles, but mastering them took time.

From 2012 to 2014, Yu Yin practically lived in the Tao Yi Street shop. Nights were spent reading ceramics books and cultural histories, since each piece reflects multifaceted influences. Beyond Jingdezhen techniques, he studied kilns nationwide.

The shop lacked a bed, so he slept on the floor.

He also scoured the “ghost market” every Monday for antique porcelain to study.

He read, verified through dialogue, practiced, and reread. After two years, he could systematically categorize ceramics and discern quality.

03 Establishing a Meticulous Handmade Assembly Line, Following Imperial Kiln Standards

With growing expertise, Yu Yin began managing the craftsmen.

Precision porcelain demands a rigorous handmade assembly line and strict systems. Despite his casual attire, Yu Yin ran Yi Lin Tang with imperial kiln-like discipline. He grouped artisans by skill and assigned specific requirements.

Each team had a leader, and everyone underwent individual evaluations.

The process began with plain bodies entering the design studio, where outlines were drafted and compositions planned. Sketches were then transferred onto the porcelain. Separate teams handled figures, landscapes, and flora/fauna.

Next, the coloring team took over, with strict quality checks at each step. Flawed pieces were returned. Finally, the factory head conducted a final inspection.

Yu Yin visited the production teams daily.

To him, precision porcelain requires precision management. Human involvement necessitates control to minimize errors. Only flawless coordination yields impeccable products.

To maintain enthusiasm, each design was limited. Yu Yin noticed that artisans peaked around their tenth to twentieth piece—early works were experimental, mid-phase adjustments refined their approach, but beyond forty or fifty, passion waned. Thus, monthly quotas were enforced.

Management, handled with the factory head and team leaders, honed Yu Yin’s emotional intelligence. This period accelerated his maturity—unusual for someone born in 1992.

But the hardest challenge was anticipating market trends—deciding what to make and how to define Yi Lin Tang’s style.

04 Devoting One Series Yearly to Pure Self-Expression

“Had I not been born into a ceramic family, would I, as a 90s kid, appreciate porcelain?” Yu Yin often pondered this.

The answer was likely 99% no. It’s neither cool nor flashy. Ancient porcelain was elegant, a vital part of lifestyle trends, reflecting taste, status, and aesthetics. Today, it’s non-essential, disconnected from modern life.

Since ceramics captivated him, Yu Yin saw Yi Lin Tang as a platform to revive their relevance.

But Yi Lin Tang’s growth mirrored his own.

Initially, he sought to reinterpret tradition, so Yi Lin Tang produced conventional patterns. By 2014, he believed tradition belonged to the past—buyers should know history but not dwell there.

He established a rule: annually, 10%-20% of his time would be spent on a purely self-driven series.

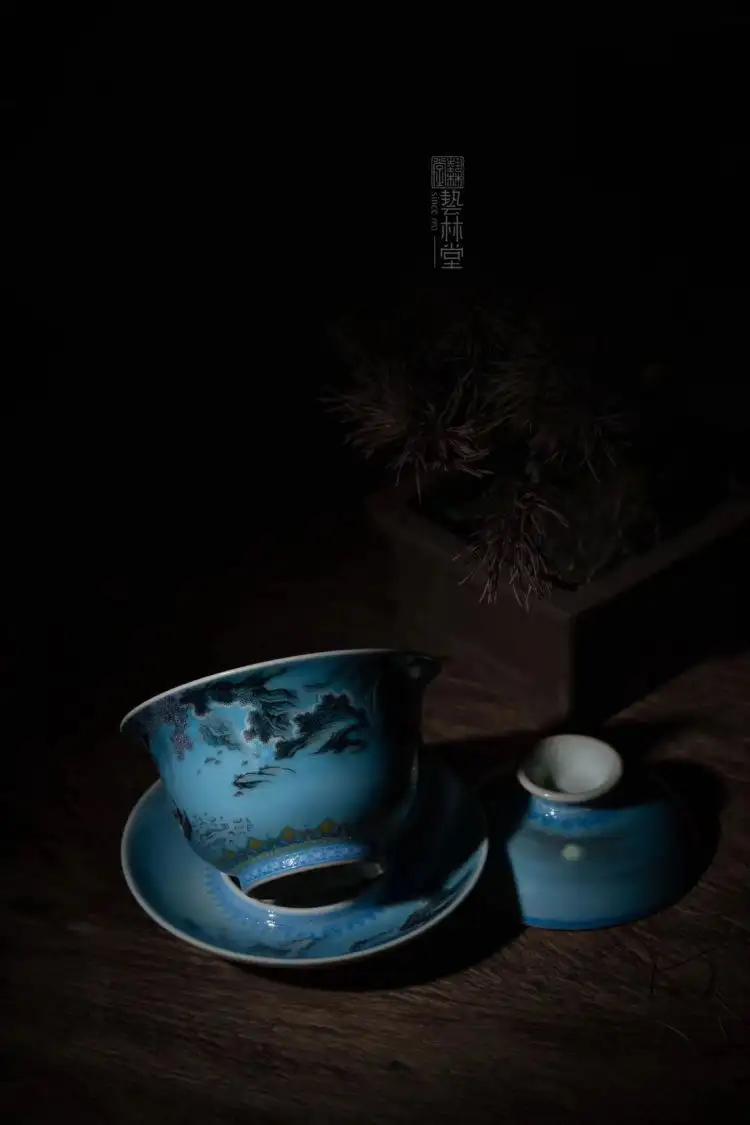

In 2015, he created the “Dream Series,” including an Alexander McQueen tribute. Using premium overglaze techniques—gold-on-gold, famille-rose, ink colors, and carnelian red—his design team spent months selecting shapes, mostly traditional: large plaques, small tea caddies, cups, and saucers.

He combined classical scrollwork with skull motifs on traditional forms. The visual contrast was striking.

At that year’s Jingdezhen Ceramic Expo, the series caused an uproar. Traditionalists recoiled—Chinese art emphasizes auspicious symbolism. “This is insane! Skulls on porcelain? Who’d buy this?”

Even distributors doubted its marketability. Yet it found an audience among bold, death-defying 80s and 90s buyers.

The McQueen series merged death with eternal vines, symbolizing rebirth—neither life nor death is absolute.

Yu Yin admired McQueen’s work. To him, designers and artists must retain childlike wonder and authenticity for their work to resonate. Though their fields differed, McQueen’s flamboyance paired with impeccable tailoring mirrored Yu Yin’s innovative aspirations.

The McQueen series marked Yu Yin’s foray into ceramic futurism. In 2016, he launched “Dream Butterfly,” followed by a Doraemon series in 2017.

When asked, “Why not Peppa Pig?” he retorted, “Doraemon honors my childhood. What does Peppa Pig mean to me?”

Criticism once riled him, but over time, he grew indifferent. He realized he wasn’t performing for anyone.

These experimental works were just a start. Now leading a 40-50 person team, his decisions hinge on market and operational realities. He innovates under constraints, often prioritizing data over personal taste.

To refine Yi Lin Tang’s identity, he categorized products into three lines:

-

Yi Lin Tang Collection: Practical ware (tea sets, incense burners, tableware) blending design and functionality.

-

Yi Lin Cang Zhen: Complex, time-intensive pieces (one per month) showcasing advanced craftsmanship.

-

Yi Lin Huai Gu: Faithful recreations of classical works, including materials. Initially averse to antiques, Yu Yin now appreciates their cultural depth—their spirit surpasses modern pieces.

He invests great effort to showcase true antique excellence, beyond superficial replicas devoid of工艺 (craftsmanship) and soul.

“Born into a famille-rose porcelain family, I stand between past and present. Our heritage grants us masterful techniques, but I sense a new era for famille-rose. I feel a duty to bridge historical artistry with contemporary aesthetics, sparking fresh dialogues.”

As the young master, Yu Yin no longer indulges in leisure or travel. His joy lies in creation and problem-solving. Beyond auctions and antique markets, he has no hobbies. Like his father, who burned midnight oil perfecting famille-rose, Yu Yin became a night owl, studying into the wee hours. Sometimes, they’d discuss ideas late at night.

The family rarely dined together. Only such dedication could fulfill Yu Yin’s initial vow: to lead Yi Lin Tang into the future, making famille-rose porcelain both artistic and accessible.