Author Archives: Admin

Chinese Agarwood

- 26 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Chinese Agarwood: The “Diamond of Woods,” A Millennia-Old Fragrant Treasure

Agarwood, revered as the “Diamond of Woods,” stands atop China’s “Four Great Incenses” (Agarwood, Sandalwood, Aloeswood, and Musk), embodying medicinal, collectible, religious, and artistic values. Its rarity, ethereal fragrance, and cultural eminence make it the ultimate pursuit for global collectors and incense connoisseurs.

Botanical Profile:

Agarwood forms in the resinous heartwood of Aquilaria trees (Thymelaeaceae) when infected by fungi or injured, developing dense, aromatic resin over decades or even centuries. Sinking in water (density >1.0 g/cm³), it’s also called “Sinking Fragrance.” Primarily found in China (Hainan, Guangdong) and Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia), top-grade “Kynam” agarwood is vanishingly rare, with wild sources nearing extinction.

I. Rarity & Formation

-

Nature’s Alchemy

-

Formation: <1% of Aquilaria trees yield resin under stress; takes 10–100+ years.

-

Global Sources: China (Hainan), Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia (“Sinensis” variety).

-

-

Grading & Market Value (2024)

| Grade | Characteristics | Price (per gram) |

|---|---|---|

| Kynam | Top-tier “soft” agarwood, numbing-cool taste | ¥10,000–50,000 |

| Sinking Grade | Density >1.0 g/cm³ (sinks) | ¥3,000–10,000 |

| Stack Fragrance | Semi-sinking, resin-rich | ¥500–3,000 |

| Yellow Ripe | Floats, mild aroma | ¥100–500 |

II. Core Selling Points (Marketing Gold Standards)

-

Medicinal Prowess

-

Compendium of Materia Medica: Relieves pain, warms the stomach.

-

Modern Science:

-

Agarol: Anti-anxiety, sleep aid (University of Tokyo).

-

90% antibacterial efficacy (vs. Staphylococcus aureus).

-

-

-

Sacred & Feng Shui Status

-

Buddhism: Supreme offering (“Agarwood connects three realms”).

-

Daoism: Key ingredient in alchemy.

-

Feng Shui: Wards off evil, attracts prosperity.

-

-

Luxury Collaborations

-

Hermès “Agarwood” perfume (¥5,000+/bottle).

-

Patek Philippe agarwood watch boxes (auctioned >¥1M).

-

-

Investment Appreciation

-

Annual ROI: 20–30% (Kynam surged 10x in a decade).

-

Auction record: Hainan Kynam sculpture (¥23M, 2023 Poly Auction).

-

III. Product Development & Market Positioning

-

High-End Line

| Product | Target Audience | Unique Selling Point |

|---|---|---|

| Kynam Prayer Beads | Monks/wealthy devotees | Single-log carving |

| Sinking-Grade Carvings | Wall Street elites | Master artisan + NFT certification |

| Agarwood Essential Oil | Middle Eastern royalty | Ancient distillation (1 ton → 20ml) |

-

Lifestyle Collections

-

Car diffusers (agarwood + magnetic tech).

-

Starter kits (with electric incense burner).

-

IV. Medicinal & Cultural Legacy

Traditional Uses:

-

Treats lung/kidney/liver disorders, ulcers, and cancer (key in Japan’s “Kyushin” heart medicine).

-

Classical Texts:

-

Ben Cao Gang Mu: “Regulates qi, warms the kidneys.”

-

Rihuazi Bencao: “Strengthens organs, soothes nerves.”

-

Modern Pharma:

-

Critical in TCM formulas like “Agarwood Qi-Regulating Pills” and “Shixiang Revival Pills.”

Epilogue:

“Where diamonds dazzle, agarwood breathes—a scent etched in time.”

“The rarest alchemy: where tree wounds transmute into sacred gold.”

Chinese Rosewood

- 26 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Chinese Rosewood: The Eastern Treasure, A Legacy in Timber

Rosewood represents the pinnacle of traditional Chinese furniture and carving arts, encompassing 5 genera, 8 categories, and 33 precious species—with Pterocarpus santalinus (red sandalwood), Dalbergia odorifera (Hainan huanghuali), and Dalbergia cochinchinensis (Siamese rosewood) as crown jewels. Its cultural significance, rarity, and investment potential make it a global darling among collectors and luxury home markets.

Definition:

Rosewood refers to tropical hardwoods prized for their rich hues and density. Standardized under China’s GB/T 18107-2017, it includes species like Pterocarpus (e.g., Burmese rosewood), Dalbergia (e.g., Vietnamese rosewood), and Diospyros (e.g., ebony). Native to Southeast Asia and Africa, with cultivated varieties in Guangdong and Yunnan, these slow-growing trees (centuries to mature) yield exquisite grains and unparalleled durability for high-end furnishings.

I. Classification & Elite Species

-

National Standard (GB/T 18107-2017)

-

5 genera, 8 categories, 33 species of dense hardwoods.

-

-

The “Big Three” (2024 Market Prices)

| Species | Characteristics | Price Range (per ton) |

|---|---|---|

| Indian Sandalwood | “King of Woods,” 800-year maturity | ¥2-5 million |

| Hainan Huanghuali | “Gold of Woods,” painterly grains | ¥10-30 million |

| Siamese Rosewood | Imperial-grade, high oil content | ¥0.5-1 million |

II. Five Core Values

-

Rarity & Investment

-

Growth: Huanghuali requires 500+ years; wild Hainan stocks near extinction.

-

Auction Records:

-

Ming huanghuali armchair (¥115M, 2021).

-

Qing sandalwood throne (¥239M, 2017).

-

-

-

Health & Eco-Advantages

-

Phytoncides: Air-purifying (scientifically proven).

-

Zero Formaldehyde: Mortise-tenon joints, no adhesives.

-

-

Cultural Status

-

Ming-Qing royalty exclusive (unauthorized use punishable by death).

-

Scholar’s aesthetic: Huanghuali desks, sandalwood brush pots epitomize refinement.

-

-

Physical Superiority

-

Density: Sinks in water (sandalwood: 1.3 g/cm³).

-

Durability: Resists decay/insects, lasts millennia.

-

-

Luxury Collaborations

-

Hermès: Rosewood clasps.

-

Patek Philippe: Sandalwood watch boxes.

-

Rolls-Royce: Interior marquetry.

-

III. Signature Products

-

Classic Furniture

-

Ming Style: Minimalist (e.g., horseshoe-arm chairs).

-

Qing Style: Ornate (e.g., dragon thrones, curio cabinets).

-

-

Artisanal Crafts

-

Scholar’s objects: Sandalwood brush holders, huanghuali paperweights.

-

Religious art: Sandalwood Buddhas, agarwood prayer beads.

-

-

Modern Fusion

-

Tea tables: Rosewood + acrylic hybrids.

-

Neo-Chinese lamps: Rosewood frames + handmade rice paper.

-

IV. Symbolic Meaning

Traditional rosewood carvings and furniture feature auspicious motifs—myths, idioms, or nature scenes—conveying blessings through:

-

Homophones (e.g., bats = “fortune”).

-

Metaphors (e.g., peonies = “prosperity”).

Epilogue:

“Where Western luxury chases trends, Chinese rosewood guards eternity.”

“Each growth ring whispers a dynasty’s legacy.”

Chinese Red Sandalwood

- 26 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Chinese Red Sandalwood: The Imperial Timber, An Eternal Treasure

As the foremost of China’s “Four Noble Woods,” Pterocarpus santalinus (Red Sandalwood) reigns supreme with its imperial grandeur, unparalleled rarity, and millennia-old craftsmanship, making it the most coveted Eastern treasure among global collectors.

Botanical Profile:

A 15-25m tall leguminous tree with 40cm diameter trunks. Features grayish bark, pinnate leaves with 3-5 pairs of ovate leaflets, and yellow flowers. Its heartwood—dense, crimson, and medicinal—is prized for architecture, instruments, and furniture. Listed as Endangered on IUCN Red List with critically small wild populations.

I. The Royal Pedigree of Red Sandalwood

-

Nature’s Luxury

-

Growth: Requires 800+ years to mature; only 15% of trunks yield usable heartwood due to hollow cores (“10 logs, 9 empty”).

-

Habitat: Wild forests survive sparsely in South India, Yunnan, and Southeast Asia.

-

Properties:

-

Density: 1.05-1.3 g/cm³ (sinks in water).

-

Oil content: Natural resins create a “glass-like” patina.

-

Color: Orange-red when fresh → deep purple upon oxidation (photosensitive).

-

-

-

Cultural Iconography

-

Forbidden City Exclusive: Ming-Qing law reserved it for royalty (unauthorized use punishable by death).

-

Feng Shui: Symbolizes imperial authority and wards off evil (“Purple Air from the East“).

-

II. The Apex of Red Sandalwood Carving

-

Regional Schools & Mastery

| School | Masterpiece | Signature Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing Style | Throne of Qianlong | Mortise-tenon joints with <0.1mm precision |

| Guangdong Style | 13 Hongs Trade Treasures | Localized Western motifs |

| Suzhou Style | Miniature Landscapes | 0.2mm openwork (“ant-leg” detailing) |

-

Modern Innovations

-

Laser scanning + hand-finishing: 98% accuracy in replicating Palace Museum artifacts.

-

Ancient dyeing: Sappanwood juice mimics oxidation, shortening aging cycles.

-

III. Six Commercial Hallmarks

-

Investment-Grade Asset

-

Auction records:

-

Qing Dragon Cabinet (HK$239M, Christie’s 2017).

-

Contemporary pieces appreciate 15-20% annually.

-

-

-

Health Benefits

-

Scientifically proven to:

-

Soothe nerves (sleep aid).

-

Inhibit 90% bacteria (respiratory protection).

-

-

-

Status Symbol

-

Bespoke services:

-

Family crest inlays.

-

DNA-based timber certification.

-

-

-

Eco-Compliance

-

CITES-certified old stock (with customs clearance).

-

Ethical alternative: African Pterocarpus tinctorius.

-

-

Cross-Industry Appeal

-

Luxury collaborations:

-

Patek Philippe rosewood watch boxes.

-

Rolls-Royce interior marquetry.

-

-

-

Digital Ownership

-

Blockchain-authenticated NFTs (one log, one token).

-

IV. Medicinal Virtues

Applications:

-

Heartwood: Treats kidney stones, rheumatism, and cancer (anti-mold properties).

-

Kino resin (from bark): Stops bleeding, heals ulcers/skin conditions (clinically validated in 1970s).

V. The Legacy of Red Sandalwood

“Rarer than gold, more eternal than diamonds—rosewood’s millennial covenant.”

“While the West still used oak, Chinese emperors legislated for rosewood.”

“Every ‘ox-hair’ grain is time’s bestowed medal.”

Chinese Boxwood

- 26 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Chinese Boxwood: The “Ivory of Wood,” A Millennia-Old Eastern Treasure

Chinese boxwood (Buxus sinica), revered as the “ivory of wood,” stands as the pinnacle material for traditional carving. Celebrated for its fine grain, golden hue, and cultural significance, it is the preferred choice for intangible cultural heritage woodcarving.

I. Natural Characteristics of Boxwood

-

Rarity & Growth Cycle

-

“A millennium barely grows boxwood”: A 10cm-diameter trunk requires over 200 years to mature, with an extremely low yield.

-

Limited habitats: Primarily found in Yunnan, Sichuan, and select mountainous regions of Southeast Asia.

-

-

Physical Properties

| Parameter | Data | Commercial Value |

|---|---|---|

| Density | 0.85–0.95 g/cm³ | Ivory-like, ideal for intricate carving |

| Color | Pale gold → Oxidized honey | Appreciates over time; no varnish needed |

| Stability | Minimal cracking | Suitable for global transport |

-

Cultural Symbolism

-

The scholar’s wood: Used in Ming-Qing literati items (brush pots, seals).

-

Auspicious meaning: Homophone for “prosperity” (旺阳), symbolizing resilience and longevity.

-

II. Artistic Features of Boxwood Carving

-

Regional Schools & Masterpieces

-

Zhejiang Yueqing Boxwood Carving (National Intangible Heritage):

-

Style: Lifelike figures (e.g., Jigong, Su Wu Herding Sheep).

-

Technique: Combines circular/openwork carving; details like 0.3mm hair strands.

-

-

Fujian Putian Boxwood Carving:

-

Style: Religious statues (Guanyin, Arhats) with natural patina finishes.

-

-

-

Technical Mastery

-

“Hair-thin carving”: Beards, drapery folds surpass machine precision.

-

“Glue-free joinery”: Traditional mortise-tenon structures, zero synthetic adhesives.

-

III. Core Advantages of Boxwood

-

Luxury Material Benchmark

-

“Eastern ivory”: Eco-friendly alternative, CITES-compliant.

-

“Hermès of woods”: Natural luster rivals rosewood at 1/3 the price.

-

-

Collector’s Appreciation

-

Oxidation: Evolves from pale → gold → honey (includes Wood Care Guide).

-

Heritage value: Qing Dynasty boxwood carvings in the Palace Museum now exceed ¥5 million.

-

-

Health & Eco Benefits

-

Natural antibacterial: Contains buxine, inhibits mold.

-

Zero formaldehyde: Meets infant-toy safety standards.

-

IV. Medicinal Properties

Parts Used: Roots, leaves (harvested year-round, sun-dried).

Functions: Dispels wind-damp, promotes qi-blood circulation.

Applications: Rheumatism, dysentery, toothache, trauma, abscesses.

Notable Qualities:

-

Its slow growth yields a grain so fine it’s often mistaken for ivory in carvings.

-

Delicate fragrance repels mosquitoes; traditional use as a hemostatic agent.

V. The Essence of Boxwood’s Value

“More eternal than ivory, warmer than gold—this is Chinese boxwood.”

“Every grain whispers the language of time.”

Introduction to Chinese Carving Arts

- 26 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Chinese Carving Arts: The Ultimate Guide to Round, Relief, Openwork & Flat Carving

China’s 5,000-year carving tradition has perfected four iconic techniques, each offering unique artistic and commercial value for global buyers. Here’s how they compare:

1. Round Carving (圆雕) – 360° Mastery

Click to learn more: Chinese Wood Carving Technology: Circular Engravure

Core Features:

✔️ Fully 3D sculptures – Viewable from all angles like Michelangelo’s David

✔️ Material versatility – Jade, wood, ivory, stone

✔️ Dynamic storytelling – Captures motion (e.g., galloping horses)

Best For:

-

High-end collectors (Museum-grade Buddhist statues)

-

Luxury interiors (Rosewood zodiac sculptures)

One sentence summary:

“When you demand perfection from every perspective – this is Chinese round carving.”

2. Relief Carving (浮雕) – Depth with Drama

Click to learn more: Chinese Wood Carving Technology: Relief Carving

Core Features:

✔️ Dimensional storytelling – Combines 2D backgrounds with 3D foregrounds

✔️ Two subtypes:

-

Bas-relief (<50% projection) – Perfect for wall decor

-

High-relief (>50% projection) – Creates shadow play

Best For:

-

Architectural ornamentation (Temple doors, palace panels)

-

Narrative art (Historical battle scenes)

One sentence summary:

“Flat surfaces come alive with 2,000 years of Chinese shadow mastery.”

3. Openwork Carving (透雕) – Light as Lace

Click to learn more: Chinese Wood Carving Technology: Openwork Carving

Core Features:

✔️ Negative space artistry – Delicate pierced patterns

✔️ Functional beauty – Ventilation + decoration (window screens)

✔️ Light interaction – Projects intricate shadows

Best For:

-

Luxury partitions (CEO office screens)

-

High-margin decor (Backlit sandalwood panels)

One sentence summary:

“Where solid wood breathes – the magic of Chinese openwork carving.”

4. Flat Carving (平雕) – Precision in 2D

Click to learn more: Chinese Wood Carving Technology: Flat Carving

Core Features:

✔️ Cost-effective elegance – Faster production than 3D carvings

✔️ Laser-ready designs – Seamlessly adapts to modern tech

✔️ Cultural coding – Calligraphy, auspicious symbols

Best For:

-

Bulk customization (Branded corporate gifts)

-

Fashion collaborations (Engraved leather goods)

One sentence summary:

“Tradition meets scalability – Chinese flat carving for the global market.”

Chinese Premium Woods: The Ultimate Guide to Boxwood, Red Sandalwood, Rosewood & Agarwood

China’s millennia-old woodcraft tradition has perfected the use of four legendary materials, each offering unique aesthetics, cultural depth, and investment value. Here’s how they compare for global collectors and designers:

1. Boxwood (黄杨木) – The “Ivory of Woods”

Click to learn more: Chinese Boxwood

Key Features:

✔ Density & Texture – 0.85g/cm³, fine-grained like ivory, perfect for microscopic carving

✔ Color Evolution – Natural pale gold → honey patina (oxidizes over time)

✔ Eco-Alternative – CITES-compliant replacement for elephant ivory

Cultural Value:

-

Scholar’s Choice: Used for Ming/Qing dynasty seals and brush pots

-

Symbolism: Represents resilience (grows 1cm/year)

Commercial Edge:

-

*”Michelangelo-level details at 1/10 ivory cost”*

-

Top use: Religious statues, luxury jewelry boxes

2. Red Sandalwood (紫檀) – The “Imperial Wood”

Click to learn more:Chinese Red Sandalwood

Key Features:

✔ Rarity – 800+ years to mature, “10 trees, 9 hollow”

✔ Physics-defying – Density 1.3g/cm³ (sinks in water), self-oiling “glass finish”

✔ Color Magic – Fresh-cut orange → royal purple (light-sensitive)

Historical Status:

-

Forbidden to civilians during Ming/Qing dynasties (punishable by death)

-

Palace Museum’s throne material

Luxury Appeal:

-

*”Priced like Tiffany blue boxes in 18th-century China”*

-

Auction record: $30M for Qing dynasty zitan cabinet (Christie’s)

3. Rosewood (红木) – The “Collector’s Benchmark”

Click to learn more: Chinese Rosewood

Key Features:

✔ Umbrella term – Covers 33 species (e.g., Huanghuali, Dalbergia)

✔ Health Benefits – Natural phytoncides (air-purifying)

✔ Timeless Designs – Ming-style furniture appreciated by MOMA

Investment Performance:

-

Hainan Huanghuali: ▲1,200% in 15 years

-

Zitan: $8,000/kg (old-growth stock only)

Marketing Hook:

-

“The Rothschilds of woods – appreciates through wars and recessions”

4. Agarwood (沉香) – The “Diamond of Fragrance”

Click to learn more: Chinese Agarwood

Key Features:

✔ Formation Miracle – 1% infection rate in Aquilaria trees, 20-100 years to resinize

✔ Sacred Scent – 3-phase aroma: cool → sweet → milky (unreplicable synthetically)

✔ Medicinal – Clinically proven to reduce anxiety (Tokyo Univ. study)

Elite Demand:

-

Kyara-grade (奇楠): $50,000/g, chewed by Japanese tea masters

-

Middle East: Used in royal palaces as “heaven’s perfume”

Positioning:

-

“Nature’s most expensive tear – wept by wounded trees”

Comparative Summary

| Wood | Best For | Price Range | Unique Edge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boxwood | Micro-carving | $50-500/kg | Machine-like precision by hand |

| Red Sandal | Heirloom furniture | $8,000-30,000/kg | The original “blood diamond” |

| Rosewood | Status decor | $500-10,000/kg | Anti-bacterial supermaterial |

| Agarwood | Olfactory art | $100-50,000/g | 1g = 1 tree’s lifetime |

Why Global Buyers Care?

-

Boxwood: Ethical ivory alternative

-

Red Sandalwood: Ultimate flex in Asian high society

-

Rosewood: Blue-chip asset with utility

-

Agarwood: Spiritual experience in solid form

Chinese Wood Carving Technology: Flat Carving

- 26 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Chinese Flat Carving: The Art of Two-Dimensional Mastery

Chinese flat carving (Flat Carving) is a traditional craft focused on surface engraving, creating exquisite two-dimensional decorative patterns through intaglio, relief, or line-carving techniques. Distinct from circular or relief carving, flat carving emphasizes the rhythm of lines and compositional aesthetics rather than three-dimensionality. It is widely used in seals, stone inscriptions, furniture decoration, and more. Below is a systematic exploration of its historical evolution, technical features, core strengths, and modern applications.

I. Historical Evolution of Flat Carving

-

Neolithic to Shang-Zhou Dynasties: Primitive Engravings

-

Petroglyphs and Oracle Bones: Early flat carvings appear in Yin Mountains rock art and the knife-carved scripts of Yinxu oracle bones.

-

Bronze Ware Patterns: Cloud-thunder and taotie motifs on Shang-Zhou bronzes, executed with shallow planar techniques.

-

-

Qin-Han to Sui-Tang Dynasties: Standardization

-

Stone Inscriptions: Han Dynasty’s Stone Gate Inscriptions and Northern Wei’s Longmen Twenty Pinnacles showcase calligraphic flat carving.

-

Jade Line Carving: Tang Dynasty jade belt plaques feature flowing “iron-wire” lines depicting foreign musicians and dancers.

-

-

Song to Ming-Qing Dynasties: Regional Maturation

-

Inkstone Carving: Landscapes and literati paintings on Duan and She inkstones.

-

Woodblock Prints: Raised-carved plates for Zhuxianzhen New Year paintings.

-

II. Core Technical Classifications

| Type | Characteristics | Representative Works |

|---|---|---|

| Intaglio | Designs recessed below the surface | Seals, stone steles |

| Relief | Designs raised above the surface | Woodblock prints, paper-cutting templates |

| Line Carving | Pure outlines (no volumetric variation) | Jade motifs, bronze inscriptions |

| Painted Carving | Colored/gilded after engraving | Lacquerware, architectural paintings |

III. Four Artistic Hallmarks

-

“Knife as Brush” Linear Aesthetics

-

Incorporates Chinese painting’s “Eighteen Strokes” techniques (e.g., “ancient silk thread,” “nail-head rat-tail”).

-

Example: Han Dynasty jade bi discs with grain patterns requiring 12-15 cuts per square centimeter.

-

-

“Treating White as Black” Composition

-

Negative space and carved motifs harmonize (e.g., seal script’s balanced density).

-

-

Material Versatility

-

Adaptable to hard (jade, stone, metal) and soft (wood, lacquer, ceramic) surfaces.

-

-

Cultural Symbolism

-

Common themes:

-

Textual: Calligraphic steles, seal engraving.

-

Patterns: Meander, ice-crack, or Twelve Symbols motifs.

-

-

IV. Competitive Advantages

-

Efficiency & Cost-Effectiveness

-

50-70% faster than circular/relief carving (ideal for mass customization).

-

Modern laser carving replicates traditional knife techniques (e.g., Suzhou nut-carved calligraphy).

-

-

Cultural Dissemination

-

Movable-type printing: Song Dynasty Bi Sheng’s clay type based on flat carving.

-

Rubbing techniques: Reproduce cultural texts via carved steles.

-

-

Modern Design Adaptability

-

Applications:

-

Luxury branding (LV’s Chinese-character engraving series).

-

Architectural cladding (stone patterns at Beijing Daxing Airport).

-

-

-

Intangible Heritage Preservation

-

Living traditions:

-

Qingtian stone carving (landscape engraving).

-

Quyang stone carving (stele line art).

-

-

V. Modern Innovations

-

Technical Crossovers

-

Digital carving: 3D scanning + CNC replication of ancient steles.

-

New materials: Laser-carved acrylic replacing ivory.

-

-

Commercial Applications

-

High-end collaborations:

-

Cartier’s “Dragon Seal” watch series.

-

Forbidden City文创 flat-carved smartphone cases.

-

-

Conclusion: The Contemporary Value of Flat Carving

Chinese flat carving distills profound culture into minimalist forms. Its enduring strengths lie in:

-

Cost-effective cultural symbolism

-

Seamless industrial integration

-

A rich database of motifs for modern design

Chinese Wood Carving Technology: Openwork Carving

- 26 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Chinese Openwork Carving: A Timeless Art of Pierced Elegance

Chinese openwork carving (Openwork Carving) is an intricate sculptural art that partially or completely pierces through materials, creating mesmerizing interplay of void and solid, light and shadow. As an advanced form of relief carving, it is celebrated for its “delicate transparency” and widely applied in architecture, furniture, and decorative arts. Below is a systematic exploration of its historical evolution, technical features, core strengths, and modern innovations.

I. Historical Evolution of Openwork Carving

-

Shang-Zhou to Han-Wei Dynasties: The Dawn of Pierced Artistry

-

Bronze Ritual Vessels: Pierced motifs (e.g., kui-dragon patterns) on Shang-Zhou zun and dou vessels marked the earliest forms.

-

Warring States Period: The lacquered wooden screen from the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng showcased early wood openwork techniques.

-

-

Tang-Song Dynasties: Buddhist Influence and Technical Refinement

-

Tang Gold & Silverware: The gilded revolving incense ball from Famen Temple, featuring double-layered openwork.

-

Song Architecture: Yingzao Fashi documented standardized wood openwork techniques like “latticed qiuwen doors.”

-

-

Ming-Qing Golden Age: Regional Mastery

-

Chaozhou Wood Carving: Multi-layered gilt openwork (up to 5 layers), e.g., Shrimp and Crab Basket.

-

Huizhou Brick Carving: Ornate window screens like those in Hongcun’s Chengzhi Hall.

-

Suzhou Nut Carving: Miniature scenes like Night Banquet at Red Cliff on olive pits.

-

II. Core Technical Classifications

| Type | Features | Masterpieces |

|---|---|---|

| Full Openwork | Complete material penetration, 3D frameworks | Chaozhou Dragon-Phoenix hanging screen |

| Semi-Openwork | Partial backing for contrast | Dongyang Hundred Birds window panels |

| Multi-Layer | 3-5 layered depth | Guangdong gilt-wood shrines |

| Inlaid Openwork | Mixed materials (wood + jade/shell) | Qing dynasty zitan treasure-inlaid boxes |

III. Five Artistic Hallmarks

-

“Penetrative” Spatial Aesthetics

-

Achieves “seen-through yet unfathomable” effects, e.g., Suzhou garden lattice windows offering “scenery that shifts with every step.”

-

-

“Thousand-Layer” Craftsmanship

-

Chaozhou’s unique process: rough carving → fine piercing → polishing → gilding. Complex works may require 360 days.

-

-

Mastery of Light & Shadow

-

Sunlight animates brick carvings; candlelight softens palace lantern patterns.

-

-

Material Versatility

-

From jade (Liangzhu cong piercings) to fragile eggshell carvings.

-

-

Cultural Storytelling

-

Themes: longevity symbols (cranes/pines), historical epics (Romance of Three Kingdoms), Buddhist scenes (flying apsaras).

-

IV. Competitive Advantages

-

Structural Innovation

-

Huizhou windows combine ventilation, light control, and security (grid density <5cm).

-

-

Irreplaceable Craft

-

Machine carving cannot replicate hand-tooled textures (“mao-diao” marks).

-

-

Cultural Premium

-

Auction records:

-

Qing zitan openwork screen (HK$210M, Christie’s 2015).

-

Contemporary Chaozhou works: $50-80K/sq.m.

-

-

-

Cross-Disciplinary Potential

-

Modern adaptations: Hermès “Chinese Lattice” scarves; Beijing Daxing Airport’s digitalized ceiling motifs.

-

V. Modern Revival & Breakthroughs

-

Living Heritage Initiatives

-

Digital archives: 3D-scanned Chaozwood patterns (108 designs).

-

New materials: LED-lit acrylic openwork installations.

-

-

Global Showcases

-

British Museum’s 2023 exhibition featured Ming ivory concentric balls (17 layers).

-

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy

Chinese openwork carving epitomizes Eastern aesthetics through its spatial deconstruction and cultural narratives. Its enduring value lies in:

-

The harmony of handcrafted warmth and precision

-

The fusion of utility and artistry

-

Traditional DNA inspiring modern design

Chinese Wood Carving Technology: Relief Carving

- 26 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Chinese Relief Carving: A Timeless Art of Precision and Beauty

Chinese relief carving is an ancient and exquisitely crafted sculptural art, widely applied in grottoes, architecture, ceramics, wood carving, and more. Below is a comprehensive introduction to its historical evolution, technical classifications, artistic features, and core strengths.

I. Historical Development of Chinese Relief Carving

Primitive Societies to Qin-Han Dynasties (Emergence and Foundation)

Early relief carvings appeared in rock paintings and pottery motifs, such as the jade pig-dragon of the Hongshan culture and the jade cong of the Liangzhu culture, reflecting primitive religious and totemic worship.

During the Qin-Han period, the Terracotta Army of Emperor Qin Shi Huang employed segmented relief assembly techniques, while Han Dynasty stone reliefs (e.g., the Wu Family Shrines in Shandong) pioneered a style combining line engraving and low relief.

Wei-Jin to Sui-Tang Dynasties (Flourishing Under Buddhist Influence)

The introduction of Buddhism propelled relief art to new heights, exemplified by the niche reliefs of the Yungang Grottoes (Northern Wei) and the Imperial Procession at Longmen Grottoes (a high-relief masterpiece later looted and scattered overseas).

The Six Steeds of Zhao Mausoleum (Tang Dynasty) blended realism and symbolism, capturing the grandeur of the High Tang era.

Song to Ming-Qing Dynasties (Secularization and Refinement)

Song Dynasty wooden architectural reliefs (e.g., the Hall of the Holy Mother at Jinci) emphasized intricate details, while Yuan Dynasty ceramic appliqué (e.g., Jingdezhen’s underglaze red ware) developed three-dimensional decorative techniques.

By the Ming-Qing period, Dongyang wood carving (multi-layer openwork) and Huizhou brick carving (architectural ornamentation) reached unparalleled technical sophistication.

II. Technical Classifications of Chinese Relief Carving

-

By Depth of Carving

-

Bas-relief (Low Relief):

Depth < 1/2, e.g., Han Dynasty stone reliefs and Shoushan stone banyi carvings. -

High Relief:

Depth > 1/2, with pronounced three-dimensionality, e.g., the guardian figures at Longmen Grottoes and divine kings at Lingquan Temple.

-

-

By Technique

-

Openwork Carving:

Partial hollowing for enhanced light and shadow effects, e.g., Chaozhou wood carving’s gilt multi-layer openwork. -

Engraving:

Intaglio line patterns, commonly seen in steles and jade carvings.

-

-

By Material

-

Stone Relief: Longmen Grottoes, Dazu Rock Carvings.

-

Wood Relief: Dongyang wood carving, Fuzhou softwood carving.

-

Ceramic Relief: Tang Dynasty sancai appliqué, Jingdezhen embossed designs.

-

III. Artistic Features of Chinese Relief Carving

-

Line-Based Aesthetics:

Unlike Western relief’s emphasis on volumetric mass, Chinese relief prioritizes rhythmic lines, as seen in the flowing drapery styles reminiscent of Gu Kaizhi’s “silkworm-spitting-silk” technique. -

Material-Adapted Craftsmanship:

Leveraging natural textures and hues, e.g., Shoushan stone qiaose relief, where the outer layer is carved into landscapes and the inner layer serves as a backdrop. -

Philosophy of “Void and Solid”:

Using negative space and openwork (e.g., Huizhou brick carving) to evoke the artistic ideal of “treating white as black.” -

Sacred and Secular Themes:

Buddhist motifs (apsaras, bodhisattvas) coexist with folk narratives (Eight Immortals, pastoral scenes).

IV. Core Strengths of Chinese Relief Carving

-

Ancient Heritage:

Spanning from Neolithic times (e.g., Liangzhu’s divine masks, 5000 years old) to modern innovations like Li Renqing’s high-relief rubbing techniques. -

Diverse Techniques:

Encompassing low/high relief, openwork, gilding (e.g., Chaozhou wood carving), and more. -

Iconic Cultural Symbols:

Dragons, phoenixes, and auspicious clouds epitomize Eastern aesthetics, as seen in the imperial grandeur of Forbidden City reliefs. -

Global Influence:

The Imperial Procession is housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, while Hui’an stone carving shapes Southeast Asian architecture.

V. Modern Innovations and Preservation

-

Digital Restoration:

Longmen Grottoes employs 3D printing to reconstruct dispersed reliefs. -

Cultural Revitalization:

Li Renqing’s relief-rubbing techniques inspire blind-box文创, bridging tradition and contemporary life.

Conclusion

Chinese relief carving stands tall in the global art landscape for its historical depth, technical mastery, and cultural richness. It is both a testament to ancient artisans’ ingenuity and a wellspring for modern creativity. For deeper exploration of specific schools (e.g., wood/stone carving) or techniques (e.g., openwork), further discussion is welcomed!

Chinese Wood Carving Technology: Circular Engravure

- 26 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Circular Carving, Also Known as “Free-standing Carving”

Circular carving is a sculptural technique that involves creating three-dimensional artworks detached from any background, allowing them to be appreciated from all angles. In ancient China, circular carving was an art form with a long history and exquisite craftsmanship, widely applied in jade artifacts, wood carvings, stone carvings, and other fields. Below is a comprehensive introduction to the circular carving techniques of ancient China, covering its historical development, characteristics, advantages, as well as in-depth analyses and video resources available online.

I. Historical Development of Circular Carving Techniques in Ancient China

-

Neolithic Age: The Origins of Circular Carving

The earliest circular carvings date back to the late Neolithic period, exemplified by the jade pig-dragon of the Hongshan culture and the jade cong of the Liangzhu culture, showcasing the primitive exploration of three-dimensional carving by ancient peoples.These works feature simple, rugged designs and were primarily used for religious rituals or tribal totem worship.

-

Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Maturation of Circular Carving

Circular jade carvings from the Shang and Zhou periods, such as the jade figures and birds unearthed from the Tomb of Fu Hao, display remarkable craftsmanship. Often made from Hetian jade, these pieces combine vivid realism with symbolic meaning. -

By this era, circular carving techniques could depict complex movements, as seen in the high-relief dragon motifs on jade archer’s rings (jade she).

-

Han Dynasty: The Pinnacle of Circular Carving Art

Han Dynasty circular carvings, such as jade mythical beasts (bixie) and celestial horses, are characterized by fluid lines and dynamic postures. The “hair-thin carving” technique was employed to achieve intricate details.These jade carvings were often used in aristocratic burials, symbolizing power and wealth.

-

Tang to Ming-Qing Dynasties: Diversified Development

-

Tang Dynasty: Buddhist statues flourished, such as the Vairocana Buddha in the Longmen Grottoes, which combined circular and relief carving to create a majestic presence.

-

Ming-Qing Dynasties: Wood and stone circular carving techniques reached their zenith, as seen in Dongyang wood carvings and Shoushan stone carvings, with themes ranging from figures and animals to mythological stories.

-

Shang Dynasty Circular Engravure

II. Characteristics of Ancient Chinese Circular Carving Techniques

-

Strong Three-Dimensionality, 360° Viewing

Unlike relief carvings, circular carvings can be admired from any angle. For example, the boxwood carving of the immortal Li Tieguai (housed in the Forbidden City) meticulously captures the figure’s expression and drapery. -

Material-Adapted Artistry, Clever Use of Natural Colors

Artisans tailored their designs to the material’s texture and color. For instance, Qingtian stone carvings utilize the stone’s natural hues to depict flowers and figures. -

Complex Process, Multiple Steps

Traditional circular carving involves stages such as roughing, chiseling, and polishing, as seen in the production of Shoushan stone carvings. -

Profound Cultural Symbolism

Circular carvings often carry auspicious meanings, such as statues of the God of Wealth symbolizing prosperity and dragon pillars representing authority.

III. Advantages of Ancient Chinese Circular Carving Techniques

-

Longstanding Heritage

From the Hongshan culture to the Ming-Qing dynasties, circular carving evolved continuously, forming distinct schools like Fuzhou wood carving and Hui’an stone carving. -

Strong Artistic Expression

Capable of vividly portraying human expressions (e.g., the compassionate gaze of the Yuan Dynasty Li Tieguai statue) and dynamic postures (e.g., the galloping stance of Han Dynasty jade horses). -

Wide Material Adaptability

Suitable for jade, wood, ivory, bronze, and other materials, each showcasing unique artistic styles. -

Global Influence

During the Ming-Qing periods, Chinese circular carving techniques (e.g., Hui’an stone carvings) spread to Southeast Asia, influencing the sculptural arts of Japan, the Philippines, and beyond.

The ancient Chinese Circular Engravure technique is a treasure of traditional Chinese craftsmanship, and its three-dimensional expression, cultural connotation, and exquisite craftsmanship still influence modern carving art to this day.

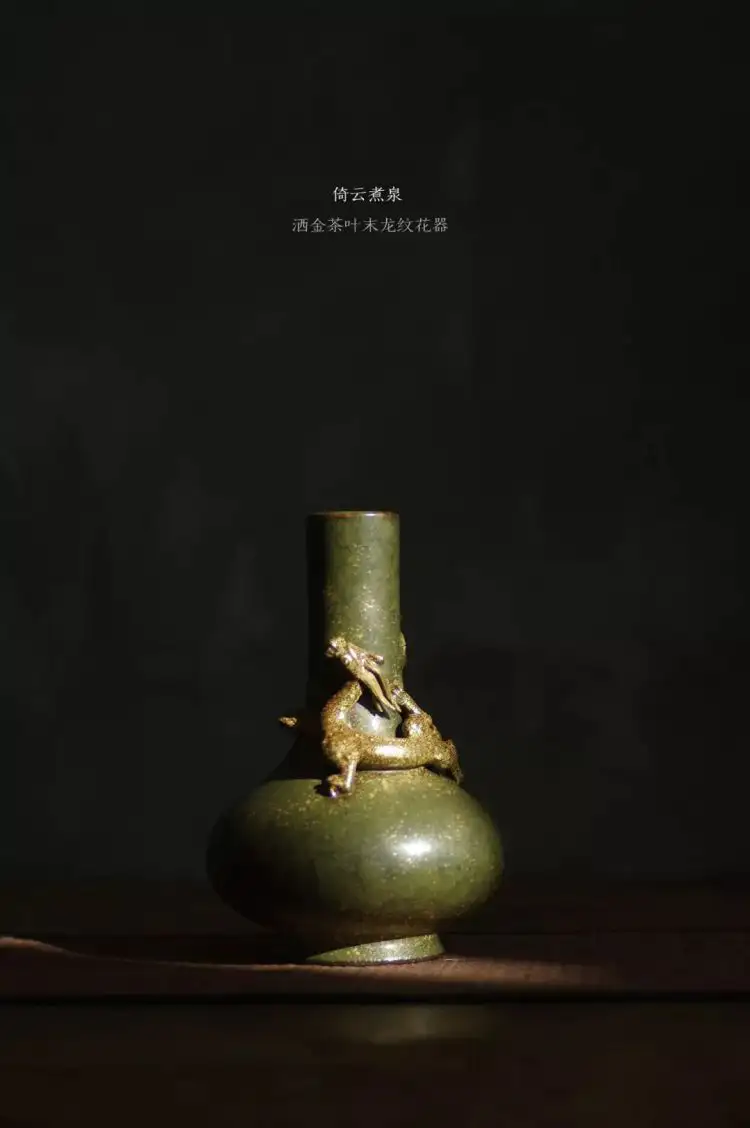

Yu Yin: Leading the ‘Aged’ Yi Lin Tang into the Future

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Yu Yin: Leading the ‘Aged’ Yi Lin Tang into the Future

This year marks his seventh since taking over Yi Lin Tang. When he first became the young master, he bore fewer responsibilities, fewer shackles, and no worries or sense of mission.

But seven years later, after meeting many people and creating countless stories with them, he began to understand what he carried on his shoulders. Yi Lin Tang grew alongside him, and every step taught him the true meaning of inheritance.

In 2012, amid a tea-drinking trend, the tea ware market boomed, with sales and prices multiplying. Many seized the opportunity to enter the industry. But twenty-year-old Yu Yin chose to turn away at this very moment. He decided to close the ceramic brand store he’d operated in Shanghai for four years.

This store had been set up with his father’s help.

In his freshman year, while studying art design in Shanghai, he wanted to drop out and start a ceramic business. His father fell silent but ultimately didn’t stop him.

Calmly, his father took Yu Yin to visit friends in the tea ware industry, negotiating deals one by one. In 2009, they secured the national distributorship for Xiaoya, a renowned Jingdezhen brand, and opened the store in Shanghai. Within three years, Yu Yin raised the price of a teapot from 300 yuan to 30,000 yuan. Continuing the business would have been a steady source of income.

But at this very moment, Yu Yin shut the store. He no longer wanted to sell others’ brands—he wanted to return to Jingdezhen and revive his family’s brand, Yi Lin Tang. His usually open-minded father wasn’t pleased; instead, he firmly opposed the idea.

01 The Yi Lin Tang Legacy Isn’t Easy to Inherit

Yi Lin Tang was founded by Yu Yin’s grandfather in 1953 and has a 64-year history. In the 1980s, Yu Yin’s father took over. Both generations devoted themselves to mastering famille-rose porcelain replication, earning high repute in the industry.

Yu Yin came to Fanjiajing—Jingdezhen’s antique porcelain hub—at the age of five. Back then, his family’s five-story building housed a display area on the first floor, living quarters on the second, and ceramic workshops on the third to fifth floors.

In his memories, the house buzzed with Southeast Asian clients who often visited. Upstairs, uncles and aunts bent over porcelain, painting diligently. He often saw his father’s back, hunched over research in solitude.

In 2003, while studying Republic-era enamel colors, his father spent days tinkering with a small scale in his room, testing samples. Even during SARS and the financial crisis, when the economy slumped, their products always sold. As he grew older, Yu Yin traveled to Taiwan with his family to meet his father’s old friends. When they brought out treasured Yi Lin Tang pieces, the conversations flowed warmly.

Though born into a ceramic family, Yu Yin wasn’t particularly fond of porcelain. He took for granted the quality of his elders’ work. His father, emotionally reserved, never explained much.

It wasn’t until he entered the ceramic business—before even turning eighteen, with his father handling the store’s装修 (renovation)—that he began to appreciate the craft. By the next year, he redesigned the store and revamped its inventory.

Dealing with ceramics meant interacting with many people. In Jingdezhen, artisans don’t care about wealth—they value your understanding of ceramics. As a dealer, Yu Yin had to offer suggestions, which required deep knowledge. The more he learned, the more he realized ceramics’ vastness. Looking back, ceramic development reflects the evolution of Chinese culture, art, and taste.

By 2010, an idea struck him: Our family’s craftsmanship is exceptional, and Yi Lin Tang has spanned three generations. If I can successfully market other Jingdezhen brands, why not our own?

But his father refused. For two years, Yu Yin pleaded, but his father remained unmoved.

His father had spent a lifetime mastering famille-rose porcelain. Like many Jingdezhen artisans, he didn’t want his descendants in the trade. Creating original famille-rose porcelain is agonizing—it involves technical communication, management, design, and R&D. It’s no easy task for a young person.

But twenty-year-old Yu Yin, bold and defiant, ignored these unseen hardships. He simply wanted to do what he believed was right.

After two years of futile struggle, he closed the store without further discussion and returned to Jingdezhen.

02 Becoming the Young Master: Two Years Living in the Shop

With no other choice, his father relented, letting Yu Yin take over Yi Lin Tang.

Starting in 2012, Yu Yin solemnly stamped “Yi Lin Tang” on the base of each piece, determined to create the world’s most beautiful famille-rose porcelain. But as his father predicted, hardship followed.

Yi Lin Tang’s two generations had focused on famille-rose research.

Famille-rose porcelain isn’t ancient.

In the late Kangxi era of the Qing Dynasty, artisans, inspired by enamel painting techniques, developed famille-rose (or “soft colors”)—a low-fired overglaze painting method. It peaked during the Yongzheng and Qianlong reigns.

The technique involves adding “glass white,” an opaque pigment that creates a soft, powdery effect, hence the name “famille-rose.”

His father assigned Yu Yin three master painters—specialists in flowers/birds, landscapes, and figures.

But Yu Yin was young. Though his father supported him, he couldn’t always guide him. Early on, communication issues arose with the masters.

“The setbacks were endless.”

At first, the masters dismissed him as a clueless kid. For instance, when a piece’s base yellowed due to smoke absorption, they claimed it was a desirable “Republic-era characteristic.”

Painters, paid per piece, resisted criticism. Skilled but proud, they only respected those who understood the craft. If Yu Yin gave uninformed advice, they’d humor him while privately dismissing him.

“My father’s reputation opened doors, but in conversations, he couldn’t speak for me. I had to learn everything myself—body shaping, glaze formulas, color development, painting techniques for landscapes, flora/fauna, and filling methods. Only then could I contribute meaningfully.”

He interacted with over a dozen specialized roles, but mastering them took time.

From 2012 to 2014, Yu Yin practically lived in the Tao Yi Street shop. Nights were spent reading ceramics books and cultural histories, since each piece reflects multifaceted influences. Beyond Jingdezhen techniques, he studied kilns nationwide.

The shop lacked a bed, so he slept on the floor.

He also scoured the “ghost market” every Monday for antique porcelain to study.

He read, verified through dialogue, practiced, and reread. After two years, he could systematically categorize ceramics and discern quality.

03 Establishing a Meticulous Handmade Assembly Line, Following Imperial Kiln Standards

With growing expertise, Yu Yin began managing the craftsmen.

Precision porcelain demands a rigorous handmade assembly line and strict systems. Despite his casual attire, Yu Yin ran Yi Lin Tang with imperial kiln-like discipline. He grouped artisans by skill and assigned specific requirements.

Each team had a leader, and everyone underwent individual evaluations.

The process began with plain bodies entering the design studio, where outlines were drafted and compositions planned. Sketches were then transferred onto the porcelain. Separate teams handled figures, landscapes, and flora/fauna.

Next, the coloring team took over, with strict quality checks at each step. Flawed pieces were returned. Finally, the factory head conducted a final inspection.

Yu Yin visited the production teams daily.

To him, precision porcelain requires precision management. Human involvement necessitates control to minimize errors. Only flawless coordination yields impeccable products.

To maintain enthusiasm, each design was limited. Yu Yin noticed that artisans peaked around their tenth to twentieth piece—early works were experimental, mid-phase adjustments refined their approach, but beyond forty or fifty, passion waned. Thus, monthly quotas were enforced.

Management, handled with the factory head and team leaders, honed Yu Yin’s emotional intelligence. This period accelerated his maturity—unusual for someone born in 1992.

But the hardest challenge was anticipating market trends—deciding what to make and how to define Yi Lin Tang’s style.

04 Devoting One Series Yearly to Pure Self-Expression

“Had I not been born into a ceramic family, would I, as a 90s kid, appreciate porcelain?” Yu Yin often pondered this.

The answer was likely 99% no. It’s neither cool nor flashy. Ancient porcelain was elegant, a vital part of lifestyle trends, reflecting taste, status, and aesthetics. Today, it’s non-essential, disconnected from modern life.

Since ceramics captivated him, Yu Yin saw Yi Lin Tang as a platform to revive their relevance.

But Yi Lin Tang’s growth mirrored his own.

Initially, he sought to reinterpret tradition, so Yi Lin Tang produced conventional patterns. By 2014, he believed tradition belonged to the past—buyers should know history but not dwell there.

He established a rule: annually, 10%-20% of his time would be spent on a purely self-driven series.

In 2015, he created the “Dream Series,” including an Alexander McQueen tribute. Using premium overglaze techniques—gold-on-gold, famille-rose, ink colors, and carnelian red—his design team spent months selecting shapes, mostly traditional: large plaques, small tea caddies, cups, and saucers.

He combined classical scrollwork with skull motifs on traditional forms. The visual contrast was striking.

At that year’s Jingdezhen Ceramic Expo, the series caused an uproar. Traditionalists recoiled—Chinese art emphasizes auspicious symbolism. “This is insane! Skulls on porcelain? Who’d buy this?”

Even distributors doubted its marketability. Yet it found an audience among bold, death-defying 80s and 90s buyers.

The McQueen series merged death with eternal vines, symbolizing rebirth—neither life nor death is absolute.

Yu Yin admired McQueen’s work. To him, designers and artists must retain childlike wonder and authenticity for their work to resonate. Though their fields differed, McQueen’s flamboyance paired with impeccable tailoring mirrored Yu Yin’s innovative aspirations.

The McQueen series marked Yu Yin’s foray into ceramic futurism. In 2016, he launched “Dream Butterfly,” followed by a Doraemon series in 2017.

When asked, “Why not Peppa Pig?” he retorted, “Doraemon honors my childhood. What does Peppa Pig mean to me?”

Criticism once riled him, but over time, he grew indifferent. He realized he wasn’t performing for anyone.

These experimental works were just a start. Now leading a 40-50 person team, his decisions hinge on market and operational realities. He innovates under constraints, often prioritizing data over personal taste.

To refine Yi Lin Tang’s identity, he categorized products into three lines:

-

Yi Lin Tang Collection: Practical ware (tea sets, incense burners, tableware) blending design and functionality.

-

Yi Lin Cang Zhen: Complex, time-intensive pieces (one per month) showcasing advanced craftsmanship.

-

Yi Lin Huai Gu: Faithful recreations of classical works, including materials. Initially averse to antiques, Yu Yin now appreciates their cultural depth—their spirit surpasses modern pieces.

He invests great effort to showcase true antique excellence, beyond superficial replicas devoid of工艺 (craftsmanship) and soul.

“Born into a famille-rose porcelain family, I stand between past and present. Our heritage grants us masterful techniques, but I sense a new era for famille-rose. I feel a duty to bridge historical artistry with contemporary aesthetics, sparking fresh dialogues.”

As the young master, Yu Yin no longer indulges in leisure or travel. His joy lies in creation and problem-solving. Beyond auctions and antique markets, he has no hobbies. Like his father, who burned midnight oil perfecting famille-rose, Yu Yin became a night owl, studying into the wee hours. Sometimes, they’d discuss ideas late at night.

The family rarely dined together. Only such dedication could fulfill Yu Yin’s initial vow: to lead Yi Lin Tang into the future, making famille-rose porcelain both artistic and accessible.

Li Yun: Mastering Antique Porcelain is Like Cultivating Martial Arts in the Jianghu

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Li Yun: Mastering Antique Porcelain is Like Cultivating Martial Arts in the Jianghu

Li Yun was born in Jingdezhen and has loved painting since childhood. After graduating from high school, he joined the Folk Special Art Research Institute under the Science and Technology Commission, where he learned ceramic painting from veteran artisans. In the late 1980s, he established his own studio, focusing on ceramic sculpture. In the early 1990s, he shifted to the production and replication of antique porcelain glazes. Over the past thirty years, he has restored many lost techniques and varieties, presenting the pinnacle of Jingdezhen’s ceramic craftsmanship through his antique porcelain works.

To outsiders, Jingdezhen’s antique porcelain circle seems somewhat mysterious. Fanjiajing is the sales hub for antique porcelain in Jingdezhen, but ordinary visitors usually only encounter mid-to-low-end replicas. The true masters are elusive, scattered in hidden corners of the city. They don’t hang signs or openly operate businesses—without a guide, it’s impossible to find them.

Yet, once you enter the circle, you realize it’s not large. Reputation and skill are everything here. The craft of replicating ancient artifacts is highly technical, and the true masters are also experts in ancient ceramics.

As for reputation, the antique porcelain circle has its own rules. Historically, Chinese ceramics have always involved later generations replicating earlier works. The ancestors set the standard: antique replication is about pursuing perfection in craftsmanship. These artisans don’t engage in forgery—they openly state that their works are replicas. What happens afterward is none of their concern. Because their works are high-value art, buyers prefer discretion, so they produce limited quantities and avoid public attention.

Li Yun is highly respected in the circle for both his skill and reputation. Low-key and amiable, he often wears a black T-shirt. His expertise lies in Qing Dynasty ceramics, particularly exquisite carved porcelain and monochrome glazes, with tea-dust glaze being his specialty.

Regardless of age, everyone in the circle calls him “Second Brother.” Wherever he goes, people offer him drinks or insist on paying for meals. He responds politely but avoids excessive socializing. At the dinner table, he steers clear of technical discussions or comparisons—he’s simply a food enthusiast who becomes talkative when the topic turns to cuisine.

In Li Yun’s eyes, antique porcelain replication isn’t as mystical as people think. It’s like cultivating martial arts in the Jianghu—progressing step by step, studying extensively, experimenting tirelessly, relying on insight and diligence. When he finally restores a lost technique, the excitement is unparalleled.

It’s this very excitement that has sustained him through the long years.

01 Outside the Family, Everything Depends on Yourself

Li Yun loved painting in his youth. In 1984, after graduating from high school, he worked at his father’s plastics factory. But the sight of the massive machines frustrated him. Fortunately, his uncle was involved in ceramics, so he left the factory and joined the Folk Special Art Research Institute on his uncle’s recommendation.

At the time, the institute housed fifty or sixty retired ceramic artisans with nowhere else to go, each possessing unique skills. Li Yun apprenticed under them, learning blue-and-white and famille-rose painting. But he found famille-rose painting too monotonous—copying the same traditional patterns day after day didn’t satisfy him.

The artisans at the institute specialized in different areas—some in shaping, others in carving. So while painting, Li Yun also learned other ceramic techniques from them. Since there were no conflicts of interest, the learning environment was excellent. The artisans shared everything they knew, and he quickly mastered carving and other skills.

After two years of training, he left in 1989.

In Jingdezhen, many make a living from ceramics. “Who doesn’t use porcelain bowls?” Back then, he entered the industry with this mindset, seeing it as a viable livelihood. Early on, he painted porcelain and carved plain ware—tasks he could do alone behind closed doors, with ready buyers for his work.

But while carving, he noticed that intricate details could be lost if the glaze wasn’t applied correctly. In those days, Jingdezhen wasn’t as open as it is now, and colored glazes were hard to come by. The formulas were closely guarded by a few technicians and families, inaccessible without connections.

He tried buying pre-made glazes but found that even with the technician’s formula, his pieces still failed. He didn’t know the right glaze thickness, firing temperature, kiln atmosphere, or whether to maintain heat during the process.

Li Yun dislikes relying on others. Faced with these challenges, he delved into glaze research. At the time, the field was largely unexplored. Starting with transparent glaze, he gradually studied red, green, and blue glazes. The more he learned, the more he marveled at the depth of traditional colored glazes.

“At first, I had grand ambitions—like mastering the best sacrificial red glaze.”

The process of experimentation, verification, and refinement was grueling yet thrilling. Gradually, his mindset shifted from seeing it as a livelihood to a genuine passion.

By chance, he met Chen Yelin, a pivotal figure in his life. Chen had resigned from the Ceramic Institute to start a private ceramic company, becoming one of the earliest entrepreneurs in the field. Impressed by Li Yun’s talent, Chen offered him a workshop in Fanjiajing—originally a warehouse—to produce antique porcelain.

They agreed to split any profits; if there were none, so be it. This opportunity brought Li Yun to Fanjiajing, where he hung a sign for an “Ancient Ceramics Research Institute” and began his studies.

From 1989 to 1999, Li Yun experienced rapid growth, coinciding with Fanjiajing’s transformation. When he first arrived, Fanjiajing was known for vegetable farming and tofu production. In the 1990s, a wave of “antique fever” swept regions like Southeast Asia, attracting buyers from Hong Kong and Singapore.

The wave of reforms and market demand dramatically changed life in Fanjiajing. Crowds flocked to open ceramic workshops, and antique porcelain was sold in the People’s Square, about a kilometer north.

Some buyers sought Li Yun out, bringing damaged pieces and asking him to recreate them. This pushed him to keep learning. Li Yun has a researcher’s spirit—he’s willing to invest time and has his own methods.

“Over the years, I’ve learned to do everything myself. When I asked others to prepare glazes, the results weren’t what I wanted. So I took matters into my own hands. I’ve been on my own for a long time—I don’t like relying on external help. Since leaving home, I’ve been self-made.”

02 Antique Replication is a Profound Technical Craft

What exactly does antique porcelain replication entail? Some in the industry compare it to the dedication of scientists developing the atomic bomb.

The inheritance of each glaze color has faced multiple catastrophic interruptions.

For example, during the Yongle and Xuande periods of the Ming Dynasty, techniques reached unprecedented heights. The “fresh red” glaze, also called “drunken red” or “gemstone red,” was renowned for its rich hue and became a rare treasure. However, due to the difficulty of high-temperature copper-red glaze firing and strict material requirements, production ceased by the mid-Ming Dynasty.

By the Kangxi era of the Qing Dynasty, Jingdezhen’s kilns flourished again. After painstaking efforts, high-temperature red-glazed porcelain was successfully revived, with “bean-red” porcelain standing out as the finest.

Each historical period had its own peak glaze colors. Antique replicators aim to reproduce these pinnacle glazes and forms. But many original formulas are lost, and during repeated trials, factors like raw material ratios, firing atmosphere, temperature, and kiln positioning all affect the glaze’s final color.

Even if the process is documented, the real path must be walked again. Li Yun’s work involves retracing history’s most challenging paths.

Back then, unmarried and unafraid of hard work, he immersed himself completely.

Li Yun never acts unprepared. To excel in antique replication, one must thoroughly understand ancient works—studying their glazes, shapes, textures, and possible firing methods. Whenever possible, he examines originals in museums.

During preliminary research, he gathers as much material as possible. Historical literature was easier to find back then—he frequented Xinhua Bookstore for papers and books on ancient ceramics. For instance, when researching copper-red glaze, he collected dozens of related domestic and foreign texts, including studies on German copper-red glass.

At the time, there were two schools of thought on copper-red glaze: one advocated colloidal coloring, the other ionic coloring. Some even suggested adding carbon. He used these references to conduct tests.

Colored glazes are essentially explorations of material technology. By mixing metal oxides and natural minerals into the glaze and firing the porcelain at high temperatures, different colors emerge.

The ancients relied on experiential knowledge; today’s artisans depend on thought and rigorous science.

Much of this exploration requires long-term accumulation. For example, Li Yun once traveled to all the mining sites around Jingdezhen, marking and recording the ores. With transportation being inconvenient, he rented a taxi for days at a time, visiting historical mines to collect samples for analysis and comparison with ancient texts.

For nearby sites like Sanbao Village, he rode a bicycle, covering thirty kilometers a day to gather stones from each pit.

His mineral records helped him understand raw material conditions. For antique replicators, firsthand information is essential.

Even with all the data, replicating an identical glaze color requires overcoming many hurdles. Li Yun says he rarely takes detours, but some paths take days, others years, and some span entire lifetimes.

For instance, when he first tried replicating the “Ru Jun” glaze—a low-temperature glaze from the Yongzheng era that mimics Jun ware, with its flowing blue-purple hues—he failed repeatedly. He set it aside, only to have a breakthrough over a decade later.

“I want to restore lost ancient techniques, hoping others will carry them forward. Many talk about innovation, but there’s a boundary between old and new. Without the old, there can be no new.”

03 Gazing at the Vast Starry Sky of the Ancients

Jingdezhen’s antique porcelain industry is no monster—it represents the highest level of traditional ceramic craftsmanship. Each era’s masterpieces boast unparalleled glaze beauty and form. Replicating them one-to-one is incredibly difficult.

For example, the two tea-dust glaze washers on Li Yun’s tea table look similar to laymen but differ by two dynasties in the eyes of experts. The “eel-yellow” hue belongs to the Yongzheng period, while the greenish tint is characteristic of the Qianlong era.

Replicating only roughly and calling it innovation invites disdain in the industry. Antique replication demands perfection.

Li Yun holds deep respect for those bygone works. “They were made by the best craftsmen and teams, sparing no cost or effort. Today, thinking a small kiln can surpass that era is impossible.”

But antique porcelain once circulated only among the wealthy. Li Yun hopes to revive lost techniques in his lifetime, bringing them back into public view and daily life.

Thus, Li Yun transitioned from an antique porcelain artisan to a brand founder. He established his own brand, “Yi Yun Zhu Quan,” to develop ancient-inspired products. He tweaks glazes and corrects flaws, whereas traditional replication insists on copying even the imperfections.

Opening another door in his studio, Li Yun leads us to the production workshop. Along the walls stand seven kilns—electric, gas, dual-use, and even ones that can burn charcoal. These kilns were custom-designed by Li Yun to suit his needs.

As he walks, he inspects freshly fired pieces—some too soft in body, others in glaze. A glance reveals subtle flaws or imperfections that escape most eyes.

The craftsmen work in specialized roles, each handling a specific step. The carving, in particular, is astonishingly detailed, with steady hands at work. Li Yun moves among them, offering succinct guidance.

At his desk, piled high with books on ancient ceramics, he remains hands-on, just as in his youth, still tackling unsolved challenges.

“Extremely serious, extremely focused.” These are the words used by the Yu family of Yi Lin Tang, another antique porcelain studio, to describe “Second Brother.”

The vast starry sky left by the ancients is worth a lifetime of pursuit.

Smog: The Path to Finding Personal Style is Slow and Endless

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Zhu Zhiyuan’s studio is located in a village near the Ceramic Institute. Walking along the roadside path, it takes only a few minutes to reach this “rural villa.” Pushing open the door to the second-floor studio, slow music fills the room, and the first to greet visitors is not him but his cat.

Apart from his ceramic sculptures, the most visible things in the room are bottles of alcohol. He’s not a heavy drinker, but creativity requires inspiration, and sustaining creativity demands infusing more energy into life.

“My works are the best interpretation of myself—they are the materialization of my life, a microcosm of my thoughts.”

Utensils are part of life, and life is the source of inspiration.

Flowing water, leaping flames, drifting smoke—all exist within the vessels, materializations of my thoughts and expressions of my inner self. Self-awareness is nothing more than a process from vagueness to gradual clarity. So these expressions are no longer just about venting emotions; they can be much more.

But this isn’t important.

One cannot go from ignorance to enlightenment in just a tenth of their life—this is something that will never be fully achieved. So, I’m happy to spend time on these things, and I dislike the idea that everything must have value or meaning.

They are just fragments of my wasted life.

If wind and water erode the land to form canyons and mountains, then “Smog” can be understood as the erosion of thought upon material—slow, winding, but steadfast.

—Smog

“Smog” is not just an artistic name; it’s also the name of Zhu Zhiyuan’s studio. But beyond the studio, fans of One Piece will recognize Smog as a character from the series. He is a former Navy captain with silver short hair, wearing a large coat with the word “Justice” on the back, a pair of goggles around his neck, and the ability to turn his entire body into smoke.

In 2009, Zhu Zhiyuan arrived in Jingdezhen with a backpack to study ceramic art and design, but neither the school nor the city matched his expectations.

“When I came to Jingdezhen, the city was shrouded in a conservative atmosphere—it felt oppressive. Everywhere I looked, there were ‘masterpieces’ of porcelain, but innovation was rare.”

01 If There’s No Opportunity to Learn, Go Find It

Although his initial impression of Jingdezhen wasn’t great, he quickly found his direction. In his freshman year, he rented a studio in Xianghu with three ceramic art majors and two sculpture majors.

The cost of starting a business in Jingdezhen was incredibly low—a 300-square-meter studio cost only 6,000 yuan a year in rent.

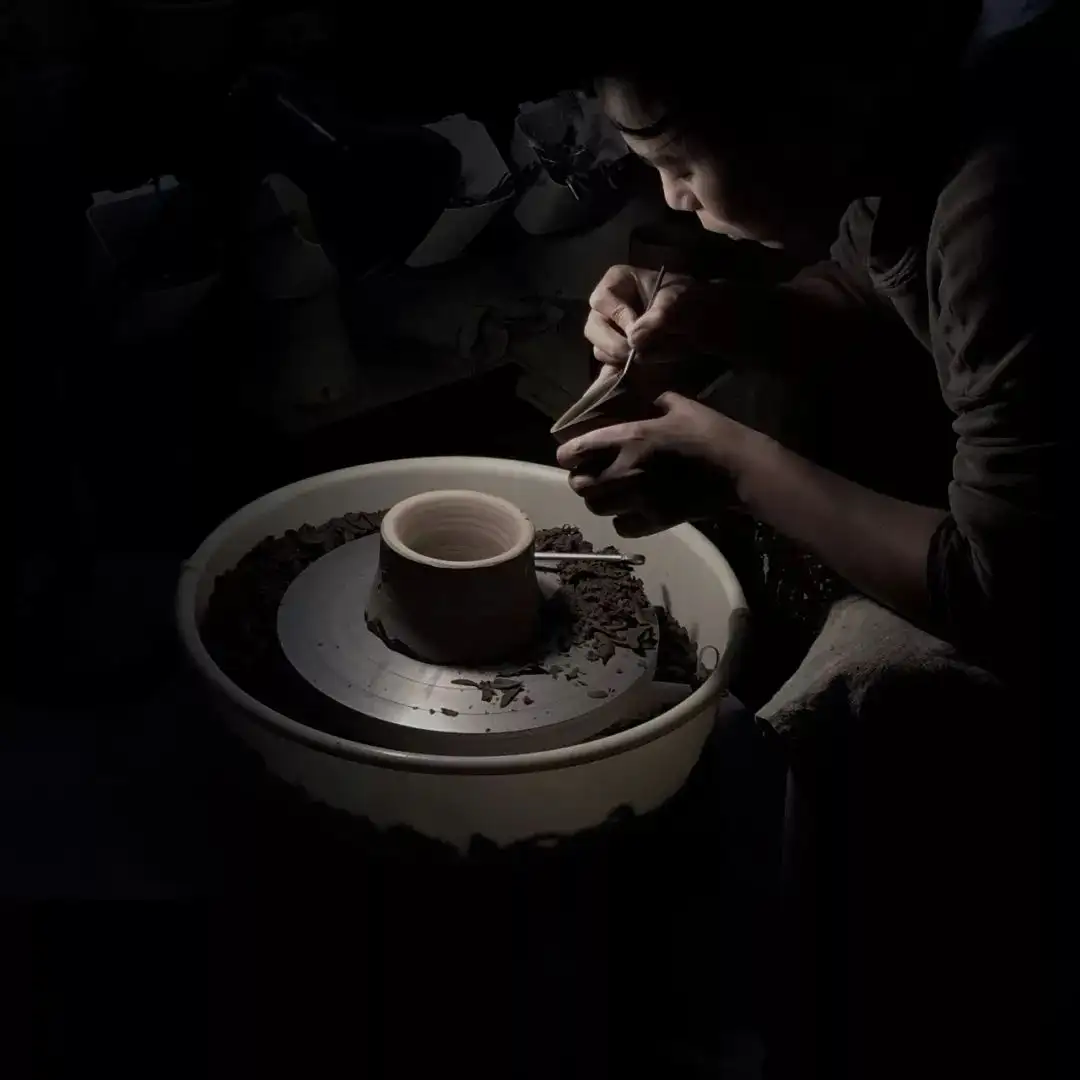

With their own studio, the group pooled money to buy pottery wheels, electric kilns, and other ceramic equipment. But even with the tools ready, the school hadn’t started practical ceramics classes yet. Learning, however, is a personal responsibility, so he began experimenting on his own. At the same time, he started learning sculpture with friends.

There was an unused pottery wheel in the studio, so they bought a ton of clay, but none of them knew how to throw pottery.

During the summer vacation of his sophomore year, with little interest in going home, he decided to stay and learn pottery throwing. He went to Laochang, where many Jingdezhen workshops were located—these were the living essence of Jingdezhen and the best teachers, showcasing the pinnacle of local craftsmanship.

The craftsmen there threw pottery with a “wild” style, their skills honed through years of experience. Zhu Zhiyuan watched them closely, observing their techniques, the rhythm of their movements. He would watch, return to the studio to practice, and if something felt off, he’d go back to observe again. He repeated this process relentlessly throughout the summer.

By the time his classmates returned from vacation, he had already mastered pottery throwing.

In his junior year, when the teacher started pottery-throwing classes, Zhu Zhiyuan jokingly asked if he could skip them since he already knew how. The teacher challenged him to throw a 20-centimeter straight cylinder, so Zhu Zhiyuan stepped up and threw a 30-centimeter one. Fortunately, the teacher was open-minded and didn’t restrict him further.

So during college, he spent most of his time in the studio, teaching himself and conducting his own research.

At the time, the Ceramic Institute didn’t have a public kiln for firing works, so he hired an unlicensed taxi to take his pieces to a public kiln at the Sculpture Imperial Kiln. Half of them broke on the way because the roads were terrible—just a little shaking was enough to shatter them.

Zhu Zhiyuan said there wasn’t a great environment for practice back then, but if you truly wanted to learn and master something, the school couldn’t provide it—you had to explore and research on your own.

02 Anxiety and Growth: The Birth of a Personal Style

Gradually, the ceramic art scene in Jingdezhen began to change. The arrival of Lety brought international resident ceramic artists, and the Lety Market, after several years of germination, began to mature, giving young people hope.

The improving environment made more young people realize that staying in Jingdezhen after graduation was feasible.

Under the leadership of Zheng Yi, founder of Lety Ceramics, more interesting young people gathered in Jingdezhen, forming a shared community. They often exchanged ideas, becoming a new force injecting vitality into the city.

After graduation, the pressures of life forced Zhu Zhiyuan to consider his livelihood. Although his ceramic skills were solid, he felt conflicted.

“I didn’t want to compromise by making functional ware.”

At the time, he was more eager to express his thoughts and emotions through sculpture, but the market for large pieces was tiny. The meager income couldn’t sustain a decent life, so he reluctantly left Jingdezhen for a while. He went to a sculpture factory to work on large-scale sculpture projects. These projects were grueling, often completed in just ten days, but the pay was good.

From early 2014 to 2015, the market began to improve, and he started to change his perspective. Making functional ware wasn’t as limiting as he’d thought—the medium was just a vehicle. As long as he infused his own way of thinking into the work and took it seriously, the results would naturally be outstanding.

He experimented with making many oddly shaped teapots—some large, some small, each one unique. Even though the works weren’t yet mature, the market gave him a boost of confidence at this critical moment.

At the time, his teapots sold for over 200 yuan each, and every time he set up a stall at the Lety Market, they sold out. His monthly sales reached over 40,000 yuan, which excited him. He realized that people didn’t reject his style—at least some could accept it. The early affirmation of his teaware strengthened his resolve to stay true to himself.

As his style began to emerge, it garnered both praise and criticism. Some felt his teapots were impractical, and his ideas were still too superficial.

With newfound confidence, he began refining his style further.

Starting from the essence of ceramics, he studied clay, glaze, and firing temperatures. He bought different types of clay, experimented with adjustments, and tested strong versus weak reduction firing. At the same time, on his teacher’s recommendation, he went to Yixing to learn techniques for making tea ware, gradually considering the user’s experience.

“When you want to express certain ideas, you must rely on yourself to deeply understand and master the material. I’ve never believed in leaving the results to fate—who are you kidding? If a work isn’t complete, it’s because you haven’t mastered it enough.”

By 2016, friends remarked that Zhu Zhiyuan’s growth was visibly rapid, and his style began to stabilize. Everything seemed to be moving in a positive direction.

Elements of sci-fi, metallic textures, and dynamic expressions gradually appeared in his works.

03 The Lonely Life Enthusiast

Walking into Zhu Zhiyuan’s studio, it’s immediately clear that he’s a life enthusiast. He enjoys listening to post-rock while working, cooks lavish dinners for himself paired with his collection of wines, keeps two cats, and sports a distinctive bohemian wave perm.

But he’s always been a bit lonely—not because he’s single, but because he cherishes his independence.

The end of 2016 marked a special turning point in Zhu Zhiyuan’s life. By then, he had finally solved his financial problems. His tea ware was in high demand, his income was stable, and he could discuss professional and conceptual ideas with close friends.

But one day, he suddenly felt that if he continued like this, he’d be ruined.

In his friends’ eyes, he saw a successful version of himself—it seemed like he could just keep going down this path.

But, “Am I still myself? Am I being dragged along by the market? The superficiality of my thoughts made me seek out like-minded people for security. Is this good?”

After repeatedly questioning himself, he fell into a period of self-isolation. Finally, unable to find an outlet for his emotions, he chose to leave this environment—from Jingdezhen to Beijing, and then to Mohe.

Mohe was freezing. He’d decided to go on a whim and only bought a down jacket, completely unprepared. “I felt like I was going to freeze to death—all I wanted was to go home and sit by the stove.” Yet in this extreme environment, he realized what he truly wanted: to return to himself. “I just like black. I like metallic textures, matte finishes. I only care about myself.”

He had to hold onto these personal expressions because only then would his works truly reflect him.

To him, black is the richest form of expression—it’s not just the color it appears to be. He began formulating black glazes, from deep brown to large-grained black, matte black, fine-grained black, fluorescent black, and finally pure black.

His patterns became more stylized—comics, architecture, ethnic minority cultures, sci-fi—all elements he loved. Compared to flat lines, spirals had more tension, capturing attention. He began finding a more precise way to express this in his forms.

He often went to the river to observe small whirlpools and watched leaping flames in bonfires.

“I hope that when you see my work, it feels like a knife pressed against your forehead—that kind of feeling of oppression. It’s impactful, something you can feel immediately.”

For the next two years, he continued working on his black series, exploring more forms and styles—tea ware, incense burners, wine vessels, and highly personal sculptures.

But he was also ambitious. He didn’t want to be defined solely by black or spiral patterns. He wanted to create works with tension and weight—as heavy as mountains, as lively as flames.

He remained in a state of self-contradiction.

On one hand, he faced life’s pressures—he’d bought a house and had monthly mortgage payments. On the other, he desired change and wanted to keep pushing his boundaries. Many artists bravely abandon the styles that made them famous to pioneer new ones. But he felt he wasn’t yet capable of that. His expressions could still be more complete, and he hadn’t yet gained widespread recognition. Everything was just beginning.

▲ Solaris Series—Memories of Fire

The path to finding one’s style is an adventure in another dimension—a journey of dreams and passion.

Perhaps, as he wrote at the beginning, none of this has any real meaning. It’s just a beautiful waste of time, belonging entirely to him.