Deng Xiping: Walking a Long Path No One Has Taken Before

Born in the 1940s, she was a university student cultivated by the nation, and thus, she resolved to use her knowledge to serve her country. Once she embarked on the path of learning ceramics in Jingdezhen, she never looked back. Devoting her life’s knowledge and skills to the production of color glazes was a decision she never regretted.

Her scientific achievements showed people of that era that education was valuable and that women, too, could make industry-shaping contributions in the field of scientific research.

01 The Door to a New World

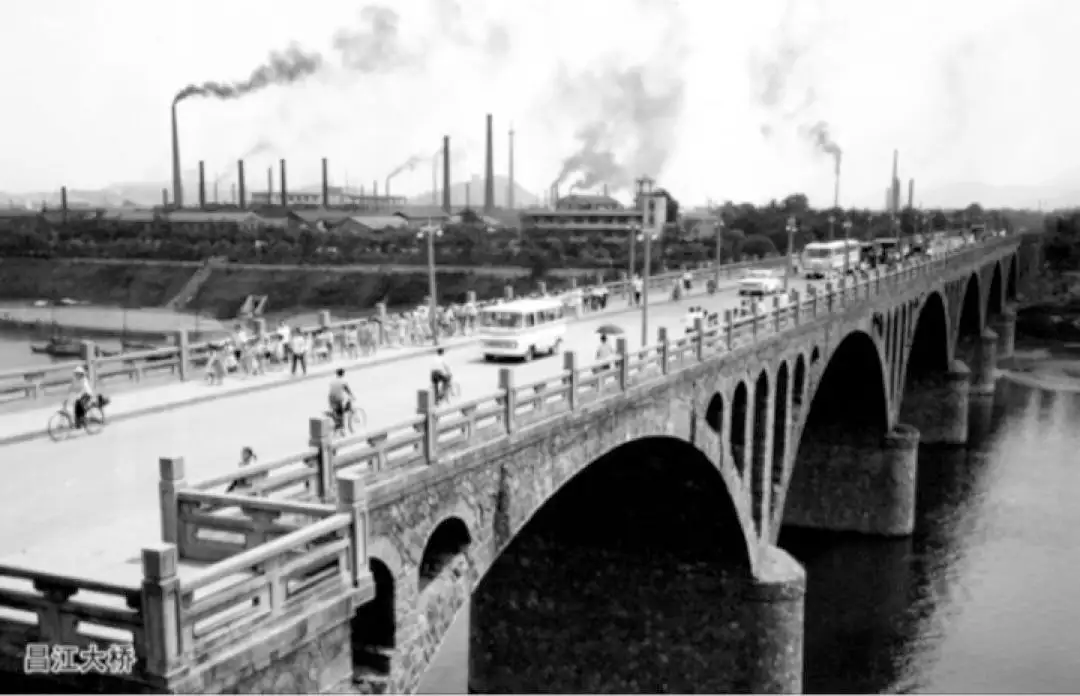

In the summer of 1965, Deng Xiping boarded a long-distance bus from Nanchang to Jingdezhen. The vehicle rattled endlessly along a muddy road covered in gravel, and the scenery outside grew increasingly desolate. In the sweltering heat of August, the bus had no air conditioning, and her white shirt was soaked with sweat. The closer she got to her destination, the more anxious she felt, as if she were being taken to some remote mountain valley she knew nothing about.

That year, she was 23 years old, freshly graduated from the Chemistry Department of Wuhan University, and assigned to work at the Jingdezhen Ceramics Research Institute under the Ministry of Light Industry. On the map, Jingdezhen didn’t seem far from Wuhan. The student affairs office at Wuhan University had planned her journey: take a boat from Hankou to Jiujiang, then a train from Jiujiang to Nanchang, and finally a bus from Nanchang to Jingdezhen.

The entire trip took three days. To save on the two-yuan daily accommodation fee, she spent one night at Jiujiang Railway Station and another at Nanchang Bus Station. By the time she finally boarded the bus to Jingdezhen, she was utterly exhausted.

Aside from her, there was another boy on the bus who had been assigned to work at a Jingdezhen porcelain factory. When they asked about directions to their respective workplaces, a doctor from the Industrial and Mining Hospital on the bus mentioned that a car was coming to pick him up and offered to take the two students along. When the bus arrived, a vehicle did indeed show up—but unexpectedly, it was an ambulance.

Deng Xiping recalled her first day in Jingdezhen: covered in dust like a clay statue, with her luggage yet to arrive, she rode an ambulance to the Ceramics Research Institute. A personnel officer led her to the girls’ dormitory, arranged for her to take a shower, gave her a change of clothes, and she went straight to bed.

The next morning, she walked around the institute and found the environment surprisingly pleasant—lush trees, flowers, and neatly arranged buildings, nothing like the remote mountain valley she had imagined. Her anxious heart gradually settled. This was her first time away from home and the first stop in her life after leaving campus.

That first year in Jingdezhen remains the happiest in Deng Xiping’s memory.

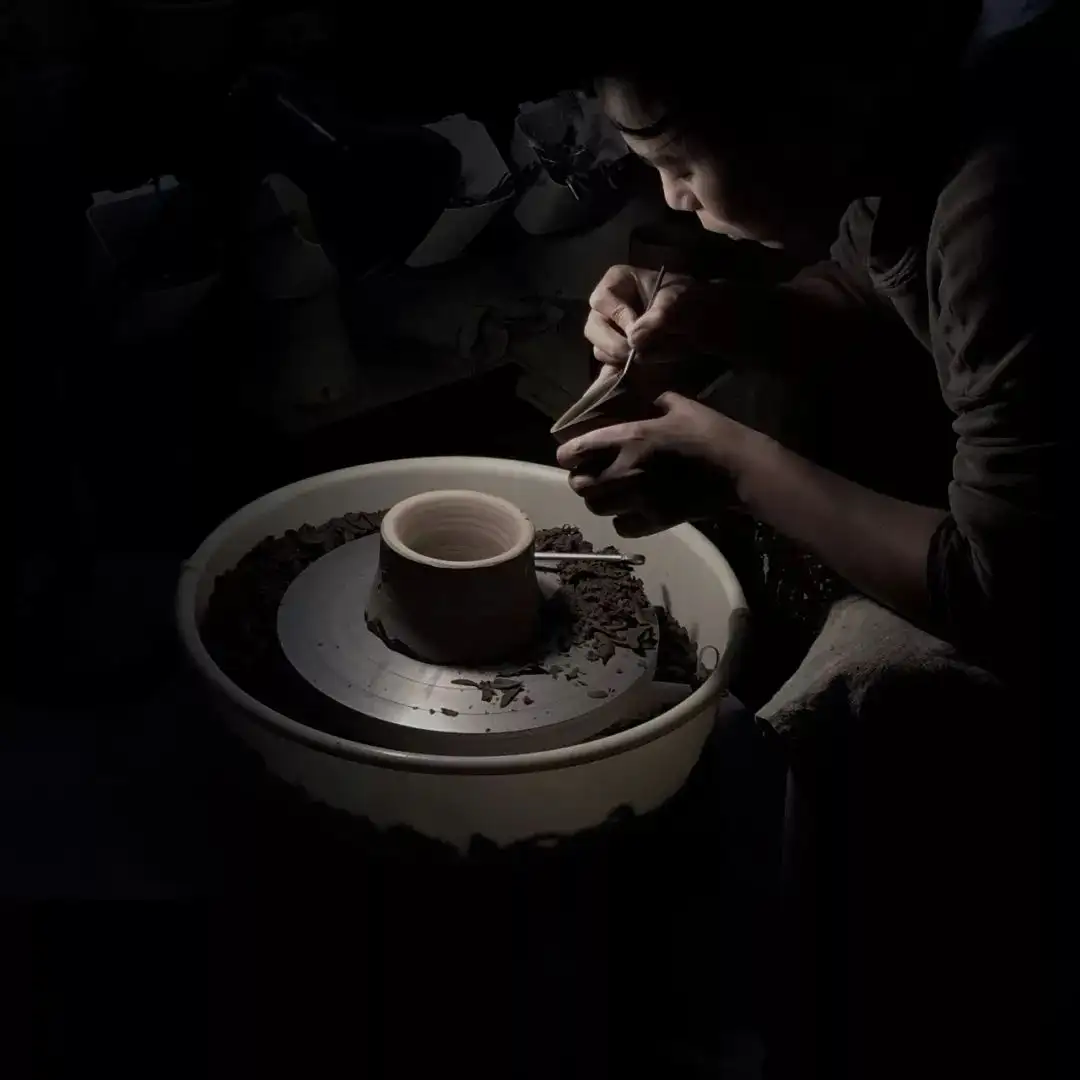

Five college graduates had been assigned there that year. At the time, the Socialist Education Movement was underway, and many new graduates were sent to rural areas to participate. However, the institute allowed these five students to stay and undergo labor training in its experimental factory. Engineers were arranged to teach them ceramic craftsmanship, and they were assigned to train in every step of ceramic production, completing an entire course in ceramic technology within a year.

As the group leader, she and the others not only worked but also handled the institute’s cultural and propaganda activities. The two female students broadcast daily news at the institute’s radio station, while the male students were responsible for the daily bulletin boards.

Deng Xiping was a highly capable learner. Born into an intellectual family, she had shown remarkable academic talent from the moment she fell in love with studying. She excelled in every subject, especially physics and chemistry.

At Wuhan University, she majored in analytical chemistry, a discipline that emphasized both theoretical and practical skills. During experiments, students were required to design their own procedures, with teachers only verifying feasibility. Success depended entirely on execution. After each experiment, a debriefing session was held where the fastest and best performers shared their methods, while the slowest analyzed their challenges, fostering improved thinking and hands-on skills.

This experimental training enabled her to quickly adapt to new tasks. Though she had no formal education in ceramics, she gained a preliminary understanding of ceramic craftsmanship after just a year of training.

02 From Researcher to Color Glaze Apprentice

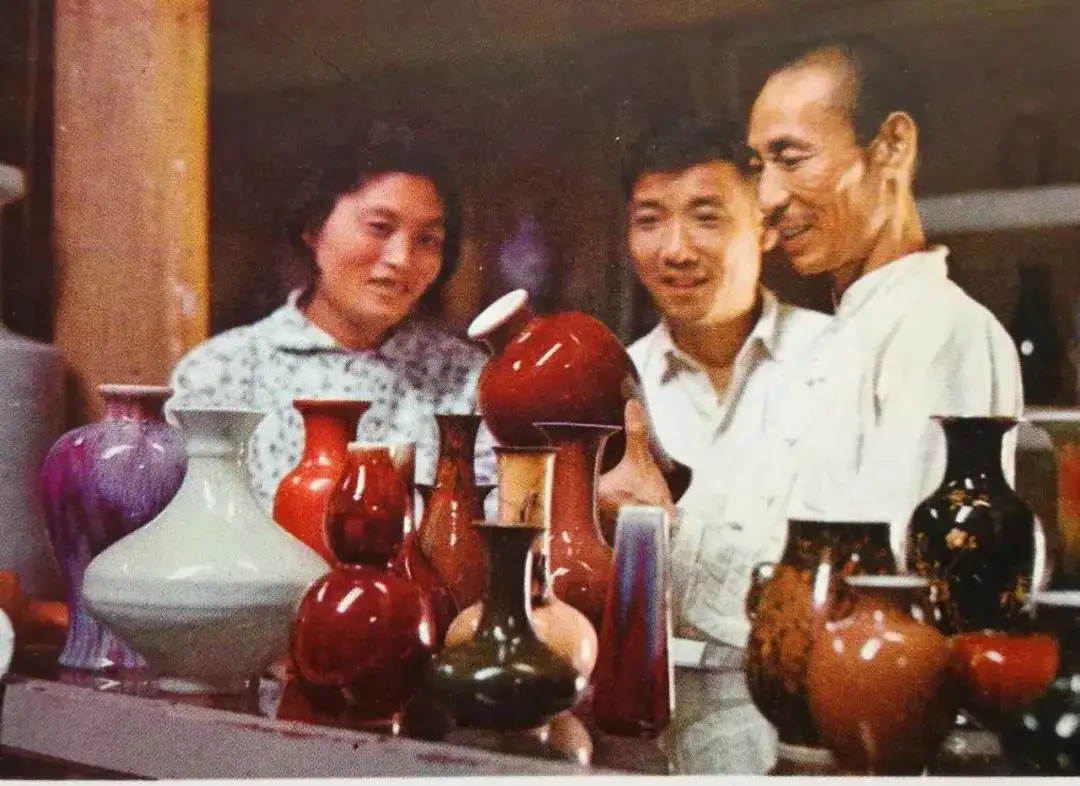

In 1966, the five graduates were assigned to different departments. The three boys were sent to research labs as technicians, and the art student was assigned to the art research department. But Deng Xiping was placed in the color glaze group as an apprentice.

▲ Deng Xiping in her early years, learning color glazes from her masters

She couldn’t understand this decision. “Why were the others assigned as technicians, while I had to be an apprentice?” Later, the political director shared a story that finally clarified her doubts.

In 1954, China urgently needed precision instrument manufacturing technology from East Germany, but the latter demanded an exchange for Jingdezhen’s color glaze technology. At the time, precious high-temperature color glazes in Jingdezhen were family secrets, passed down only from father to son, with many on the verge of being lost. The Ceramics Research Institute had gathered some inheritors of these techniques, offering them government jobs to collectively restore the craft.

However, these masters had little formal education. They knew how to prepare glazes but not the underlying principles, making it impossible to compile technical documentation. Thus, the state brought in ceramic experts and engineers from the Shanghai Silicate Research Institute, along with a group of recent graduates and young technicians, assigning each master two students to document the color glaze porcelain production process.

The masters followed ancestral methods, while the students recorded the raw materials used, sent samples to the Shanghai Silicate Research Institute for testing, and documented the entire process—from glaze preparation to application and firing. After six months, a complete set of technical data was compiled.

This document, known as the “Sino-German Technical Cooperation Data,” was exchanged for “East Germany’s Precision Instrument Manufacturing Technology,” contributing significantly to China’s early industrial development. It was the first scientific documentation of Jingdezhen’s traditional color glaze porcelain production, revealing many secrets and paving the way for future learners.

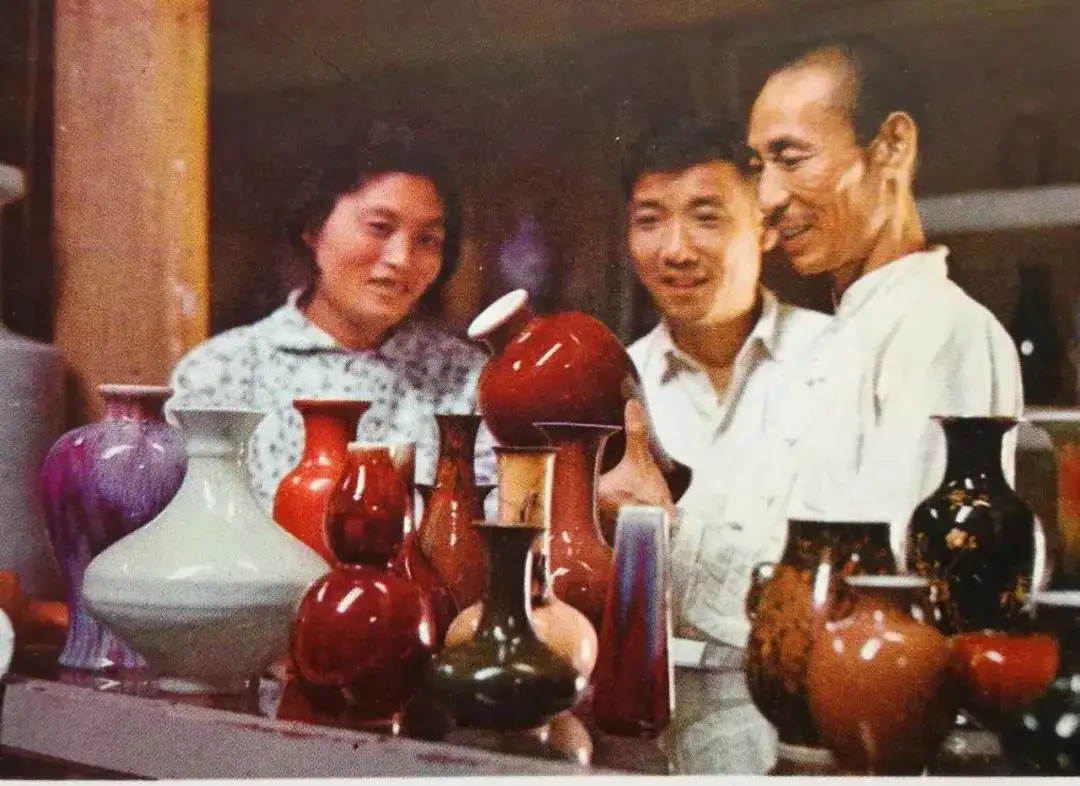

From the 1950s onward, the Ceramics Research Institute selected a few outstanding graduates or young technicians each year to apprentice in the color glaze group. Deng Xiping joined in 1966, becoming part of the last group to learn directly from the masters. At the institute, she studied under masters Nie Wuhua and Chen Honggao.

Her masters taught her to identify raw materials by touch, sight, and even taste. When she didn’t understand something, she would consult library materials. To test firing conditions (temperature, pressure, and atmosphere curves), she had to overcome old superstitions—such as the belief that women entering kilns would cause them to collapse—to install test pipes.

Traditional Jingdezhen porcelain-making involves 72 steps, each affecting the final outcome. She followed her masters to mines around Jingdezhen, recording mineral compositions. They also sourced ingredients from traditional medicine shops, such as pearls, agate, and germanium. Historically, artisans even used gold, silver, and precious stones to create color glazes.

Perhaps it was the unpredictable nature of color glazes that fascinated her. Her relentless pursuit of knowledge helped her endure the hardships of learning.

Deng Xiping was thrust into this niche field of research, unaware that she would spend her entire life immersed in it. This world was boundless, filled with endless questions waiting to be answered.

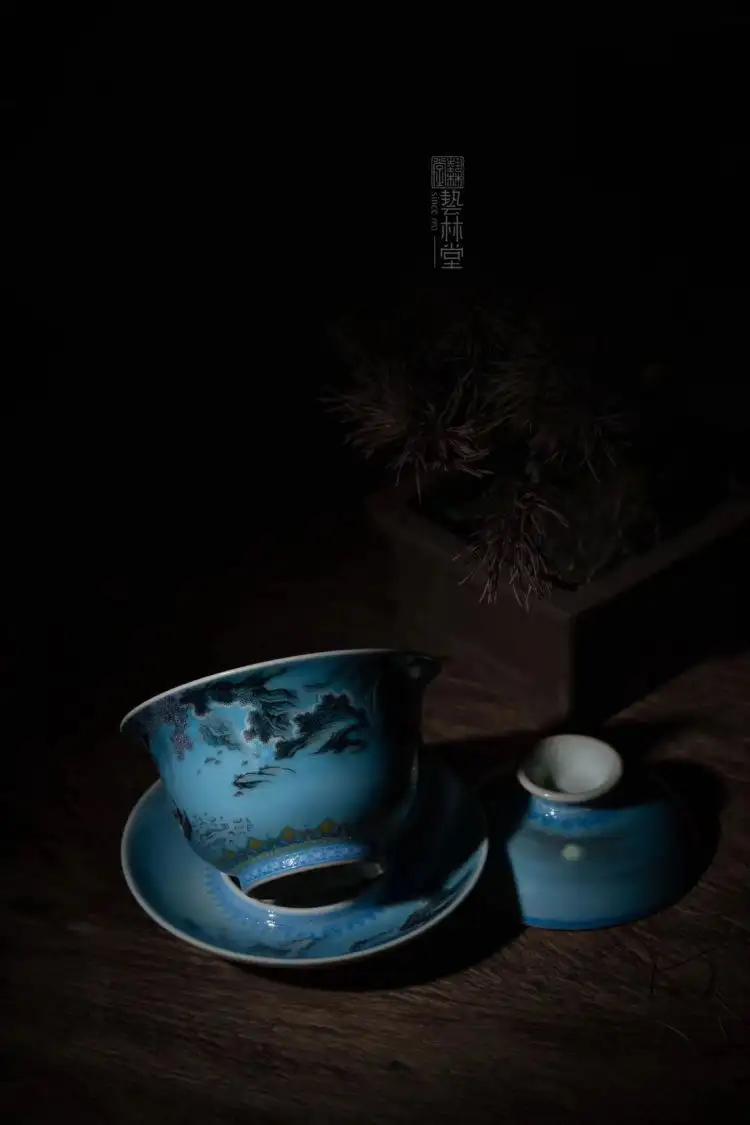

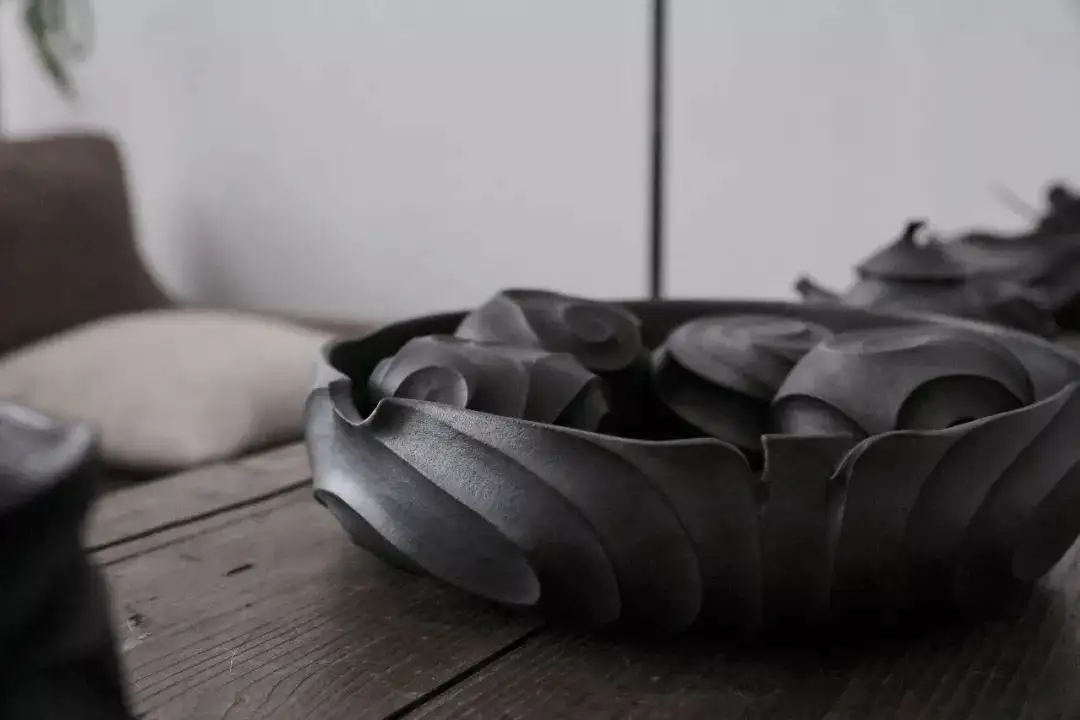

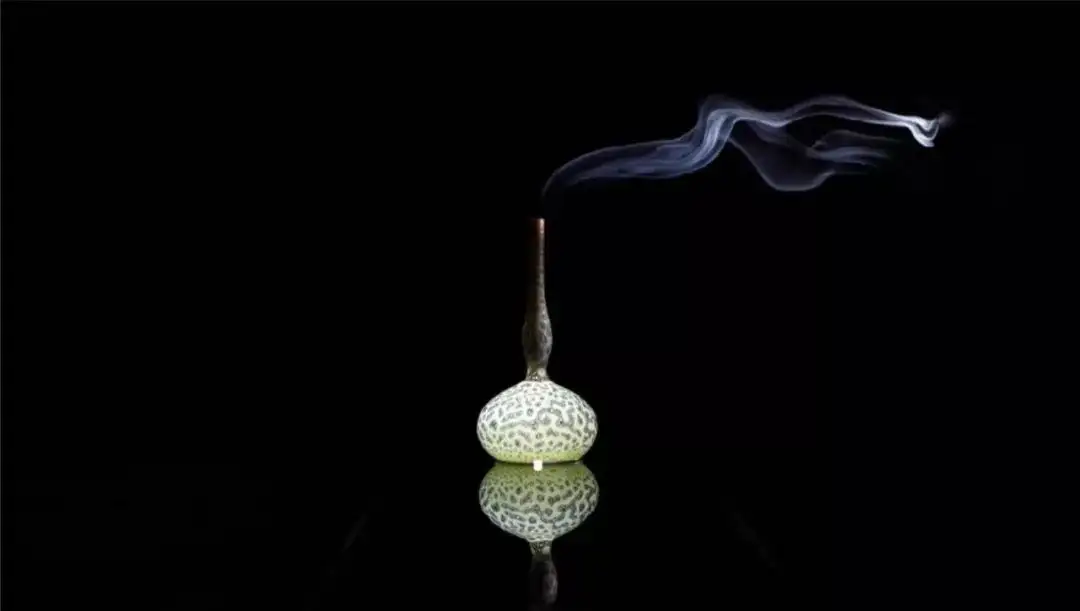

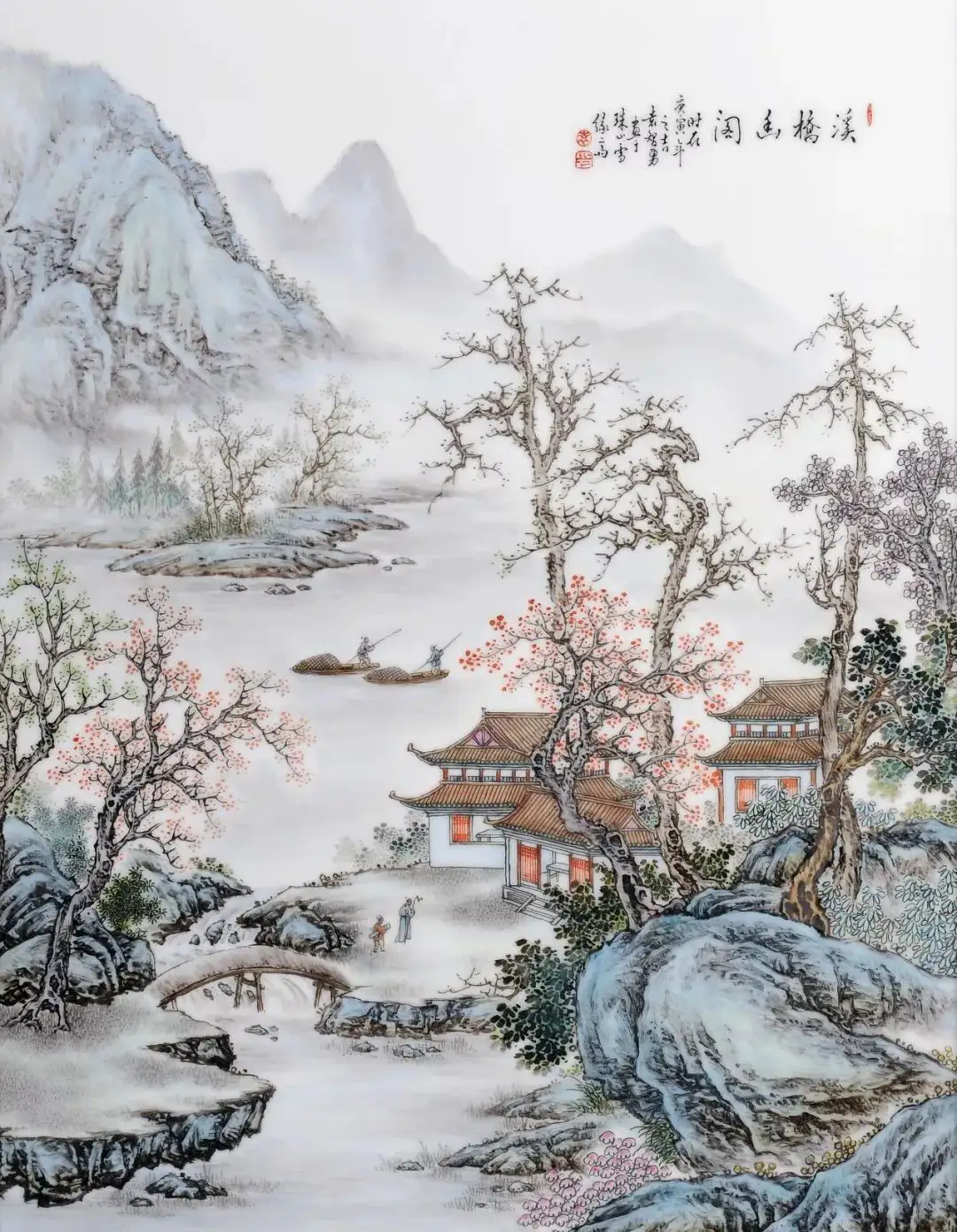

Glaze is the “clothing” of ceramics. Ancient artisans used white as the starting point and black as the endpoint, expressing their spiritual world through color. Variations in raw material ratios, firing conditions, temperature, and kiln positioning all influence the final hues, creating a dazzling array of colors.

High-temperature color glazes, as an independent form of ceramic decoration, represent one of the earliest methods in history. They focus on the craft itself and the exploration of materials, using natural minerals to create glazes that, after high-temperature firing, form gem-like structures. Known as “man-made gemstones,” they are one of Jingdezhen’s four traditional porcelain treasures.

Due to the uncertainty of kiln changes, the yield of colored glazed ceramics is very low, and the difficulty of firing is very high. In the early Qing Dynasty, during the reigns of Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong, Jingdezhen’s porcelain industry reached its historical peak, and the color glaze also entered its heyday. But at the same time, the royal family imposed strict regulations on the production and use of colored glazed ceramics.

The colored glazed porcelain produced by official kilns during the Ming and Qing dynasties was not allowed to be produced by civilian kilns. If this rule is violated, those who commit serious crimes will be beheaded. According to Volume 161 of the Annals of Emperor Yingzong of the Ming Dynasty, in the eleventh year of the Zhengtong reign (1446), an order was issued to prohibit the private production of yellow, purple, red, green, blue, blue, and white blue and white porcelain by the Raozhou Prefecture in Jiangxi Province. The first offender, Ling Chi, was executed, and Ding Nan served as a border guard from his family’s wealth. Those who knew but did not report it were punished by the imperial court. With strict laws, it ensured the royal monopoly on colored glazed porcelain.

And precisely because of this monopoly, its inheritance has also undergone multiple destructive generational changes. Just like the once prominent sacrificial red glazed porcelain that disappeared in the mid Ming Dynasty, it was not until the Kangxi Dynasty of the Qing Dynasty, under the hard research and exploration of porcelain workers, that the lost copper red glaze firing technology, which had been lost for more than a hundred years, was restored to create Langyao red glaze.

The birth of each glaze color involves dozens of complex minerals, which contain many variable trace elements. It is alive and constantly changing.

You have no way to control it, you can only adapt to it, “Deng Xiping described this special technology as follows. Nowadays, many minerals no longer exist, and finding alternative methods requires a lot of empirical exploration. In addition to studying glaze formulas, there are also many top secret operating techniques involved, which are the inheritance of experience.

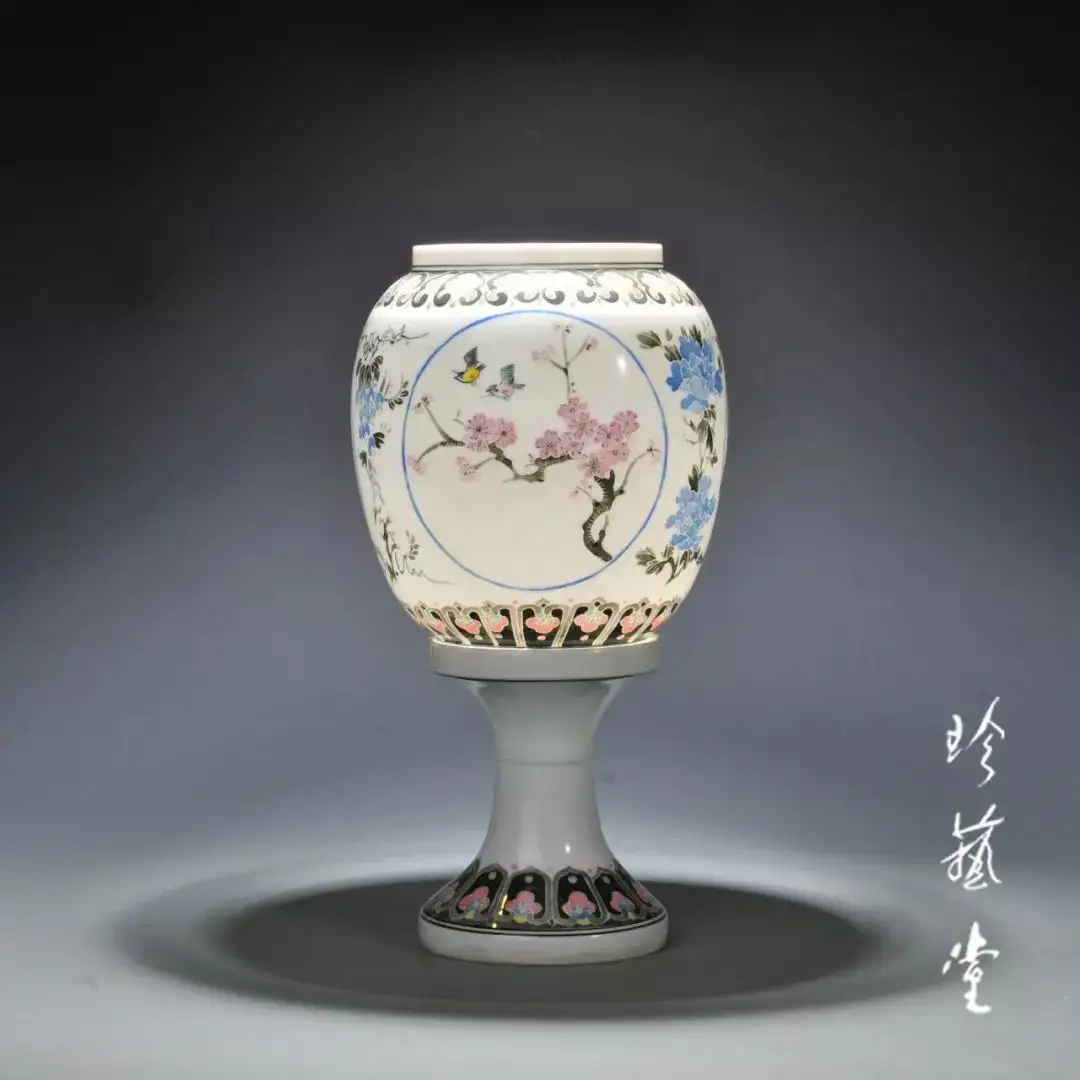

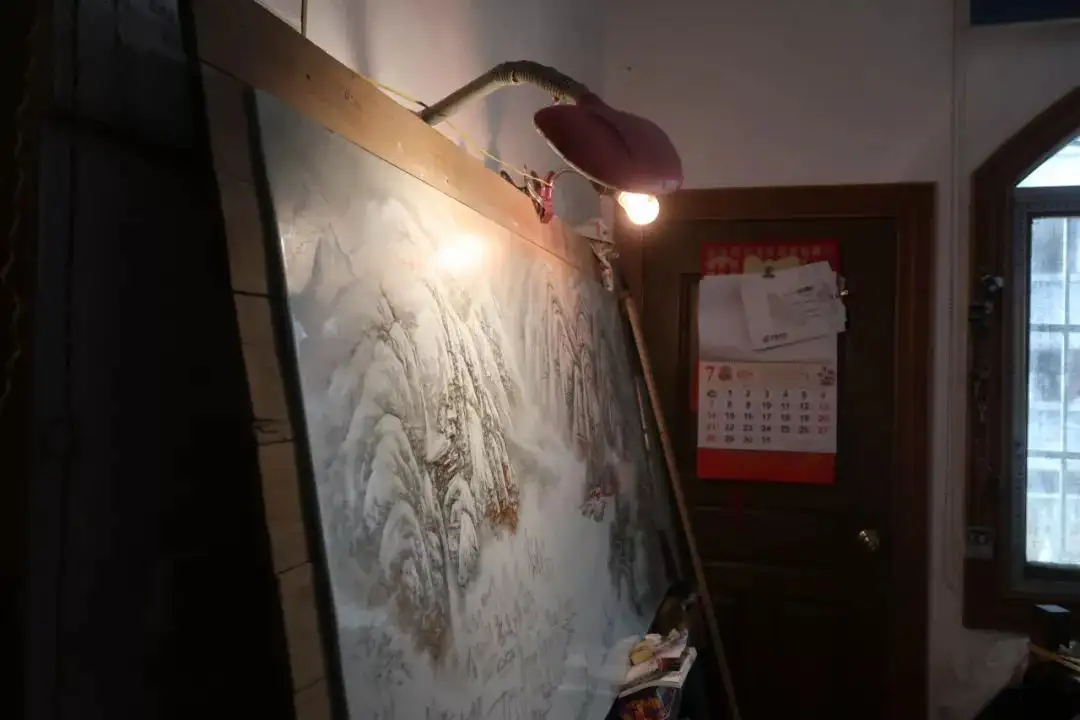

She recalled that in 2013, she restored the kiln transformation techniques of the Tang Dynasty’s “secret porcelain” that had been lost for thousands of years and the Ming Dynasty’s “flowing Xia porcelain” that had been lost for 600 years, and successfully developed the “secret glaze flowing Xia cup” on a piece of work through innovative fusion. This success lasted for 23 years, and the hardships involved can be imagined.

▲ Large Bowl of Flowing Clouds

When she was at her wit’s end in the experiment, she would temporarily pause for rest. However, since entering this research, these experiments have been constantly in her mind. As soon as inspiration arises, she immediately starts experimenting. It is this relentless persistence that has enabled her to achieve breakthroughs in both thinking and technology, and to reach the pinnacle of the field of color glazed ceramics.

03 Burn out the “Jun Hong” glaze,

On the day of being commended

If it weren’t for the tempering of the times, Deng Xiping might have quietly worked on his research projects at the Ceramic Research Institute of the Ministry of Light Industry, and then lived a plain life.

But after the founding of New China, it went through many changes. The period of the Cultural Revolution was undoubtedly a dark and bleak time for intellectuals. ‘Stinky Old Nine’ was synonymous with Chinese intellectuals in the 1960s and 1970s, ranking them among ‘local, wealthy, anti, bad, and right-wing’.

In 1968, the research institute was dissolved.

Deng Xiping was demoted to Jiangcun Commune in Jingdezhen. The pain in her heart is that she couldn’t do scientific research during the best time of her life.

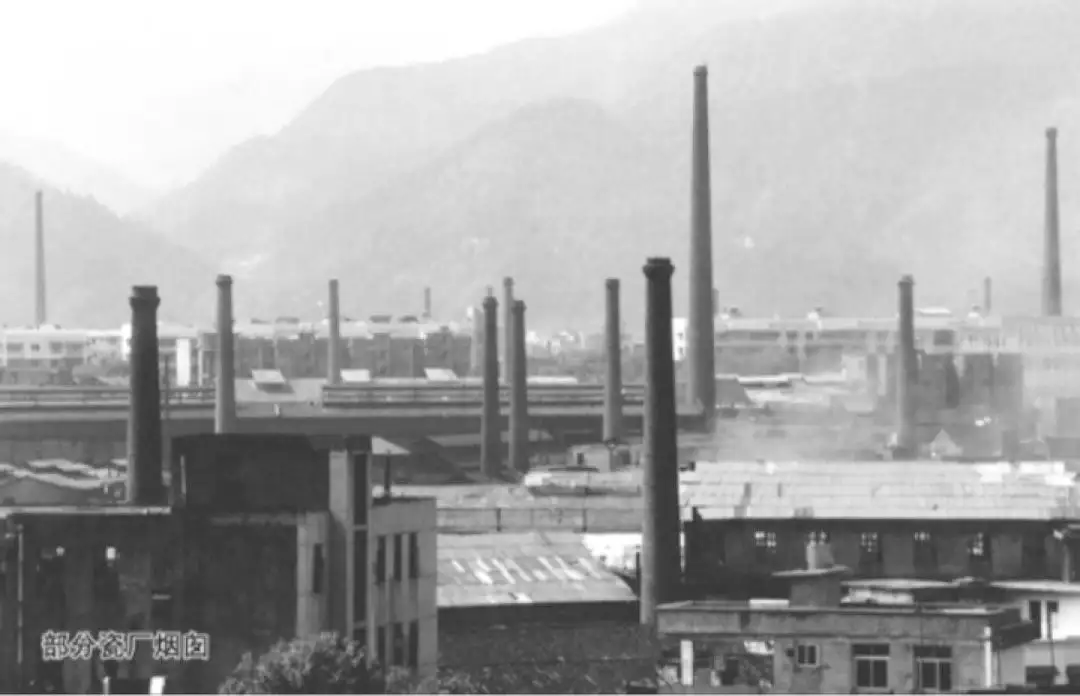

In 1972, the demoted cadres were reassigned to their original positions, and Deng Xiping voluntarily went to Jianguo Porcelain Factory. The reason for making such a decision is that she is well aware that the research institute at this time still needs time to recover, but the research cannot wait for a moment. Only Jianguo Porcelain Factory is a nationally designated porcelain factory that produces traditional colored glazed porcelain.

Among them, precious colored glazed porcelain is also a national gift porcelain given by national leaders during their visits and foreign heads of state during their visits to China. The products are sold to more than 120 countries and regions around the world, and the economic benefits are very good.

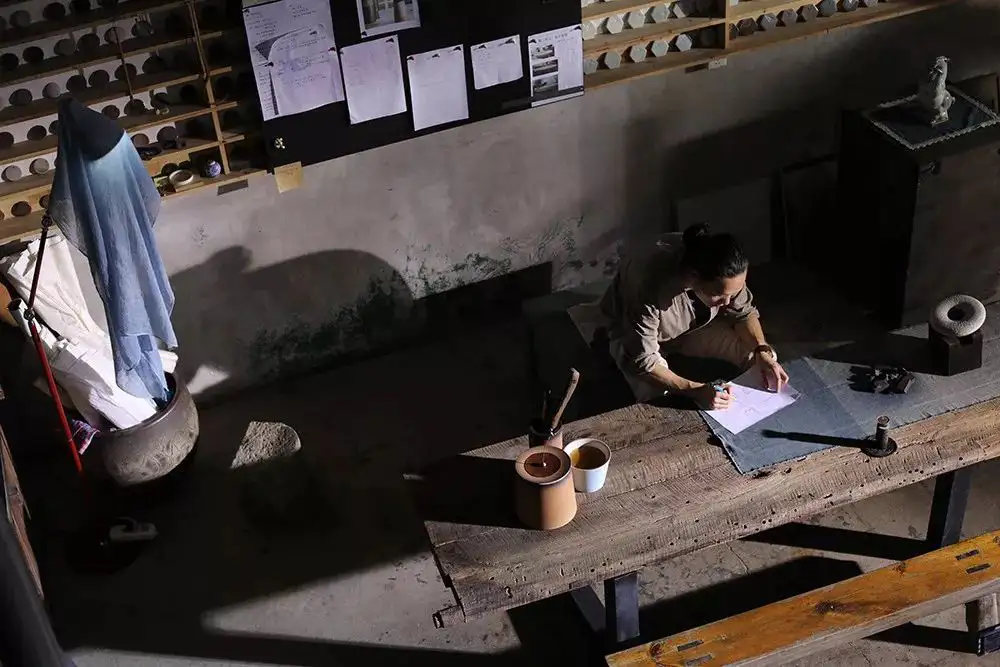

There was sufficient funding in the factory to support her research. After arriving at Jianguo Porcelain Factory, the technical director requested her to form a color glaze experimental group with two color glaze masters.

They went to collect three tables and started building a new research laboratory in a mud house that was less than ten square meters and had no windows. The factory said that if there is no experimental equipment available, please place an order and have the supply department purchase it.

But many small experimental and laboratory equipment cannot be purchased and require the cooperation of the factory’s metalworking and electrical teams for production. Making equipment is a difficult process that requires the cooperation of electricians, metalworkers, carpenters, and so on. She is the first one to arrive at the factory every day, and if an electrician is needed, she will go to the office of the electrician team and wait for the allocation of workers’ work. Half a year later, the simple laboratory was finally built.

But the challenges had only just begun. The factory respected the veteran craftsmen but was skeptical of college graduates like Deng Xiping. Conducting color glaze experiments required test pieces and clay bodies for trials.

At the time, production line workers were paid by the piece, and they didn’t believe Deng Xiping could succeed in creating color glazes. They often gave her damaged clay bodies for her experiments. Realizing this wouldn’t work, she approached the leader of the molding team and said, “If you give me flawed clay bodies, even if the glaze turns out well, the finished porcelain will still be defective, wasting state resources. If you give me good clay bodies, a successful firing will count toward your production quota, and if it fails, the technical department will issue a note to ensure your team suffers no losses.”

The molding team leader was convinced. He turned around, rummaged through a pile of finished clay bodies, and finally handed her two of the smallest ones. She thought these two clay bodies were hard-won and decided to create a color glaze that the Jianguo Porcelain Factory had never seen before—one she was confident in. In the end, she chose to recreate an orange-yellow crackle glaze she had worked on before.

Her experience in the factory had taught her that she had to handle everything personally. Once, she had placed test pieces in a specific spot in the wood-fired kiln, but when the kiln was opened, the pieces had been moved, greatly affecting the results. This time, she watched as the kiln worker placed the clay bodies in their designated spots before leaving. When the kiln was finally opened, both pieces were intact, covered in a vibrant mango-yellow glaze with large crackle patterns.

The molding team leader was overjoyed. He took the two bottles to the production department, where the leaders were astonished and praised him, saying, “The molding team can even produce new products now!” When asked who had made them, the leader replied, “Deng Xiping from the color glaze team.” From then on, the craftsmen began to cooperate with her, believing in her ability to excel in color glaze research.

In 1973, the Jianguo Porcelain Factory’s flagship product, the “Jun Red Vase,” shifted from hand-molding to slip-casting, which improved production efficiency. However, the Jun red-glazed porcelain that came out of the kiln was all cracked, forcing the entire color glaze workshop to halt production.

The “Jun Red Vase” was the Jianguo Porcelain Factory’s most profitable product. To solve this technical issue, the factory held daily meetings to brainstorm solutions.

The root of the problem lay in the fact that after the molding process was changed, the weight of the clay body was halved, making it too thin to withstand the stress caused by the Jun red glaze’s crackling. This caused the clay body to crack and the vases to break. However, the factory insisted that switching from hand-molded to slip-cast bodies was a technological advancement that couldn’t be reversed. The solution had to come from modifying the glaze, so the responsibility fell on the craftsmen in charge of the Jun red glaze. But after two months of testing, no breakthrough was made.

As the first state-owned porcelain factory in Jingdezhen and the mother factory of the “Ten Great Porcelain Factories,” the Jianguo Porcelain Factory faced severe production losses that couldn’t be justified to the state. The factory began seeking help from experienced craftsmen across society to solve the problem.

At the time, Deng Xiping’s task was to assist these craftsmen with their experiments. People came forward with suggestions in droves, keeping her extremely busy. Most of them approached the problem by trying to reduce the crackling in the Jun red glaze, but the modified glaze either continued to crack or failed to produce the red color, leaving the issue unresolved.

Deng Xiping remembered one bearded craftsman who said, “I have a family heirloom called ‘calming powder.’ If you apply it to the clay body before applying the Jun red glaze, it won’t crack.” She thought that if this powder worked, it could solve the problem, so she insisted on conducting multiple tests.

In the end, the calming powder failed, but the old craftsman gave Deng Xiping an inspiration: she needed to approach the problem differently and think outside the box.

She suddenly thought of a balloon. If you poke a balloon with a needle, it pops. But if you try to squeeze it with both hands, it’s much harder to burst. The reason is that the force is distributed evenly. In other words, if they couldn’t stop the Jun red glaze from cracking, perhaps they could make it crack more—but in a fine, dense pattern that would distribute the stress evenly, preventing the vase from breaking. This was the power of reverse thinking.

With this idea in mind, she discarded the original test formula and developed a new one based on her new approach. The test pieces soon exhibited a spiderweb-like crackle pattern. The production supervisor overseeing the tests immediately took the samples to higher-ups, and the technical director affirmed the new direction. He asked Deng Xiping what support she needed for larger-scale trials. She requested a week to produce five test vases.

To meet the deadline, she worked day and night, personally completing every step of the process and placing the pieces in three different wood-fired kilns for testing. A week later, all five vases emerged from the kiln intact. She was overjoyed, and everyone felt hopeful that the production crisis could finally be resolved.

Given the urgency, the factory skipped the pilot production phase and assigned the color glaze research team to oversee full-scale production. Production was no joke, however. The team leader, Master Zuo, was cautious and reminded Deng Xiping that this involved significant manpower, resources, and multiple steps requiring worker participation. With over 80 workers involved in the workshop, any misstep could lead to serious consequences.

To ensure smooth operations, they formed a Jun red production leadership team. The existing Jun red glaze materials in the workshop were sealed and labeled by both the technical and security departments. New materials for the revised formula were sourced directly from the supply warehouse.

Forty-eight hours later, a small portion of the prepared glaze was divided into three sealed containers and distributed to the experimental team (marked for identification), the technical department, and the security department for record-keeping. The rest was handed over to the workshop for production. As the kiln-opening day approached, Deng Xiping grew increasingly anxious, losing sleep over fears that something might go wrong.

On the day of the kiln opening, all the factory’s leaders gathered on-site. When the saggars were opened, the entire room held its breath. As each piece was revealed, not a single vase was cracked. The room erupted in prolonged applause that seemed to never end.

The success became a sensation in Jingdezhen. The factory convened a technical debriefing session for mid-level and above cadres, a day Deng Xiping would never forget. During the summary, Technical Director Yu Changsong remarked, “Education is still useful.” These words moved Deng Xiping to tears, as the stigma of intellectuals being labeled the “stinking ninth category” had not yet faded.

The statement held profound meaning for her—it was a moment when the value of intellectuals was acknowledged. From that day on, the factory’s leaders and workers changed their perception of her. No longer would she be excluded from color glaze research due to being an outsider, a woman, young, or lacking a family legacy. From then on, she could focus wholeheartedly on her work at the Jianguo Porcelain Factory.

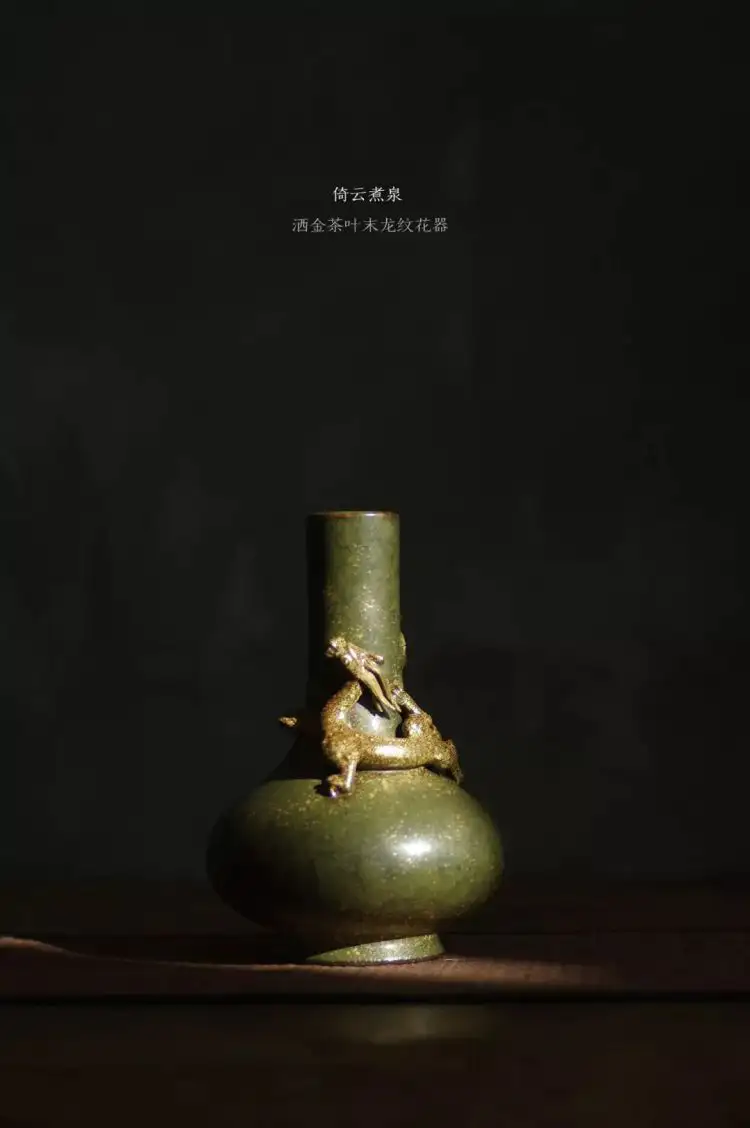

Kiln transformed flower glaze seven spiral bottle

In 1978, the National Science Conference was held, affirming the social status of intellectuals. Jingdezhen resumed its professional technical title evaluations, which had been suspended for over a decade. Deng Xiping became one of the first 40 engineers promoted in the city—the youngest and the only woman among them.

04 guarded the dismantled research institute

Carrying weight forward

In the spring of science, Deng Xiping’s mind was completely liberated. After years of research and practice, she realized that researchers must tightly integrate science and technology with production. Intellectuals and workers had to collaborate, and research outcomes required workers’ assistance to be applied in production and achieve significant impact.

She overcame numerous technical challenges. In 1978, her project “Using No. 0 Diesel to Fire Jun Red Glaze” won the Jiangxi Provincial Major Scientific and Technological Achievement Award. Through this project, she developed the No. 62 lead-free Jun red glaze, breaking the historical rule that copper-red glazes couldn’t achieve their color without lead. This innovation pointed the way toward eliminating lead from all color glaze formulas, freeing workers in the field from the threat of lead poisoning and creating immense social benefits.

In 1985, her “New Formula for Large-Scale Lang Red Glaze” won the National Award for Scientific and Technological Progress. In 1989, her “Ceramic Rainbow Glaze” project earned the National Invention Award, and in 1990, her “Rainbow Glaze Artistic Porcelain Plates” won the Gold Medal at the Brussels Eureka World Invention Expo.

After 1984, Deng Xiping served as deputy director and chief engineer of the Jianguo Porcelain Factory. Building on the experimental team, the factory officially established the Color Glaze Research Institute. New products and processes emerged continuously, driving rapid advancements in the development and production of color-glazed ceramics.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the “Three Suns” glaze alone was presented as a national gift to foreign leaders and dignitaries over 40 times. These were the Jianguo Porcelain Factory’s most glorious years. However, as reform and opening-up deepened and the market economy developed, the state-owned factory system revealed many flaws, such as inefficiency, lax management, low productivity, and severe waste.

At its peak, the Jianguo Porcelain Factory employed over 3,700 people, but only about 1,000 were frontline production workers. The factory faced mounting losses, and in the months before restructuring, it couldn’t even pay salaries. Reform of state-owned enterprises was imperative.

In October 1995, the Jianguo Porcelain Factory underwent restructuring, transforming from a single state-owned entity into over 40 independent economic units. These units were contracted by responsible individuals who used the factory’s existing facilities and equipment to organize production. The workers in each unit had to support themselves. Contractors were required to have a sense of social responsibility—they couldn’t lay off employees or reduce wages.

The first batch of contractors consisted of morally upright individuals with leadership capabilities, mostly workshop directors and Party branch secretaries, along with some well-respected team leaders. As a factory leader, Deng Xiping had to implement national policies. By the time of the restructuring, she was already 53 years old.

Her heart was filled with reluctance and helplessness, but what pained her most was the thought of abandoning the research institute she had built with her own hands.

At the time, neither the institute’s Party secretary nor its director dared to take on the contract. The researchers were mostly older, with higher salaries, and had been away from frontline production for years. The institute had no production workshops or equipment of its own. Taking on the contract meant producing goods to sustain themselves, which posed significant challenges. However, everyone was passionate about color glaze research and unwilling to leave the institute.

As the supervising director of the research institute, Deng Xiping couldn’t eat or sleep over the contracting issue.

At her age, she could have chosen early retirement, and many private companies had offered her jobs. But she knew that if the research team disbanded, Jingdezhen’s only color glaze research base would be lost. Ongoing projects would halt, the development of traditional color glazes would be delayed, and rebuilding the institute in the future would be extremely difficult.

She couldn’t abandon these research achievements and walk away alone, so she had no choice but to lead the institute forward.

Thus, under exceptionally difficult circumstances, she embarked on a second entrepreneurial journey in her life. She and her husband had worked in state-owned units their entire lives and had little savings, with two children in university. She and the research team had to rely on pooled wages and loans based on her reputation to raise operating funds and weather the difficult startup period.

Without equipment, Deng Xiping leveraged her good reputation and connections to borrow materials and machinery from other units in the factory, repaying the debts in installments.

Without a workshop, the factory allocated a 200-square-meter abandoned oil storage space as their production site. A 50-ton oil tank still sat atop the space, and removing it required a crane rental costing 1,000 yuan—a sum the factory couldn’t afford. Deng Xiping persuaded a friend to purchase some of the factory’s stockpiled porcelain to raise the money for the crane.

The new entity set up a makeshift workshop in just eight days. Deng Xiping recalled racing against time, competing with the market.

Without a kiln, Deng Xiping arranged to fire their porcelain at the Nanguang Ceramics Company. During this period, a group of former researchers pushed carts loaded with clay bodies from Shengli Road to Shuguang Road in Jingdezhen.

At the time, the “Three Suns” product was the best-selling on the market, with first-grade pieces fetching 420 yuan each and high demand. For the research team, producing “Three Suns” wasn’t technically difficult, but many researchers hadn’t personally worked on color-glazed porcelain in years, having mostly supervised workers. There was a big difference between guiding others and doing the work oneself.

As a result, they encountered numerous issues in the production process. Additionally, since they relied on borrowed kilns, they couldn’t control the firing quality. In the beginning, almost none of their “Three Suns” pieces met first- or second-grade standards, and even third-grade pieces were rare. Most were unsellable fourth-grade or worse.

San Yang Kai Tai Flat Belly Bottle

“When it rains, it pours.” While waiting for funds to purchase materials and pay salaries, their porcelain kept turning out poorly. Yet instead of blaming each other, they sat down together to analyze the problems, encouraging one another to overcome the challenges.

For the first three years of the contract, the entire team worked without a single weekend or holiday off. Any profits went immediately toward repaying debts, followed by ensuring employees’ livelihoods—their wages had to match societal standards to keep them motivated to continue developing new products and researching.

Other companies came to poach their workers, but not a single person left Deng Xiping’s team before retirement. Reflecting on those days, Deng Xiping recalled the hardship, the setbacks, and the struggles, but she also saw it as a rare and valuable life experience. After three years, the debts were cleared, and the situation began to improve. Once solely focused on research, she was now forced to learn marketing, face the market, set prices, and promote products.

She realized how difficult it was to conduct research in an open market environment—it required human, material, and financial support to go far. She was grateful she had persevered. Without this base and this team, color glaze research would have undoubtedly been delayed.

In 2010, with the support of the Jingdezhen municipal government, Deng Xiping established the Deng Xiping Ceramic Art Gallery and the Jingdezhen Color Glaze Ceramic Art Research Institute. In 2013, she founded the Jingdezhen Mingfangyuan Deng Xiping Ceramics Co., Ltd., which features a 2,400-square-meter exhibition hall displaying over 1,000 types of color-glazed porcelain she developed or innovated over 50 years. This created a new platform for cultural exchange and display of color-glazed porcelain art, now attracting over 10,000 visitors annually for tours and study.

Thinking about heritage, she called her daughter, a graduate of Southeast University, back to her side to personally teach her the craft of color glazes. Her daughter now shoulders the task of sharing color glaze knowledge with the outside world, encouraging more young people to join the ranks of research and inherit.

That day, when we met her, the originally scheduled two-hour interview stretched into five hours. She spoke so passionately that she even forgot to eat, only stopping after repeated reminders from her staff.

She reminded me of a line from the movie Forever Young: “What this era lacks is not perfect people, but those who act with sincerity, justice, fearlessness, and compassion from the heart.”

Born in the 1940s, she repeatedly emphasized that she was a college student cultivated by the nation and thus must use her knowledge to repay the country. Applying her lifelong scientific knowledge and skills to the production of color glazes was a decision she would never regret.

Over half a century, she innovated more than 40 types of color glazes and replicated over 1,000 traditional color-glazed porcelain varieties for production. Her research on the “hidden floral patterns in kiln-transmuted glazes” led to the creation of entirely new glaze types like “Phoenix Feather Glaze,” “Feather Silk Glaze,” “Plume Glaze,” and “Rainbow Glaze,” elevating Jingdezhen’s kiln transmutation technology to unprecedented heights.

Looking back to 1965, the road from Wuhan to Jingdezhen—no one could tell her what lay ahead, for they had never walked it. How far the road stretched, only she would know by taking step after step. Though the path ahead was unclear, walking it allowed her to see her own heart and find her direction.

From youth to white hair, dedicating her youth and passion to scientific research—this was the long road she chose to walk. She walked it, so those who came after could see the light.