Siming: What Was I Doing Before and After Luck Arrived?

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Siming is one of the “Jing drifters” (artists who migrate to Jingdezhen). Born in the 1990s, she stands out for her focus on niche and unconventional techniques. While others follow trends, she delves into ancient books others find obscure, spending years researching plant ash glaze formulas to create her Peacock Glaze series.

Her work is unique yet approachable, blending ancient craftsmanship with a modern sensibility. In her, there’s a collision of ice and fire, a fusion of past and future.

Among the many Jing drifters in Jingdezhen, Siming is exceptional. Many obscure techniques are abandoned due to their complexity and the scarcity of learning opportunities. Yet, she mines ancient texts to study China’s oldest ceramic glaze—plant ash glaze.

To many, the ’92-born artist is lucky. Plant ash glaze isn’t a proprietary skill, but her Peacock Glaze cups have fetched tens of thousands at auction—a height unimaginable for most young artists just a few years into their careers.

But what was she doing before and after luck arrived?

01 Finding Her Signature Work

In May 2016, we first met Siming in Xianghu, a village across from Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute. We tried driving into the village, but the narrow roads, clogged with villagers’ honking electric bikes, forced us to retreat after a long struggle to back out.

This was no idyllic retreat—just an ordinary village where cheap rents and low startup costs attracted ceramic students to set up their first studios.

That day, Siming was facing a crisis. After a dispute with her landlord, her studio was forcibly demolished before the lease expired. The landlord claimed the space was needed for renovations—his child’s wedding. The studio was reduced to rubble, bricks scattered everywhere.

With no studio but kilns still firing, she had to find a nearby temporary space. Moving far wasn’t an option—the wood-fired kiln was immobile, and relocating risked damaging her works.

We met her in a raw three-story building near the demolished studio. Somehow, she always had a knack for improvising. On the third floor, she’d set up an elegant workspace: branches foraged from the mountains, fluttering cloth curtains, tea utensils on wooden tables, and an antique cabinet from a flea market. Temporary, yet rustic and charming.

Dressed in red with wavy shoulder-length hair, she wasn’t the effusive type. Stepping out from behind the curtain, she looked like a scene from a film.

Coming from a culturally rich family, she wasn’t frantic about survival. Her needs were simple—she and her partner often ate instant noodles for weeks. Working in the village by day and walking back at night, she overcame her initial fear of the dark.

For the first three years, the studio operated at a loss. It wasn’t for lack of skill—they just hadn’t found their signature work. They experimented relentlessly, filling the studio with trial pieces.

Then came the Peacock Glaze series.

▲Peacock Glaze tea bowls

By chance, they discovered wood-fired ceramics, an ancient craft with unique allure. Early pottery wasn’t glazed; vessels gained a glassy sheen from natural ash deposits. This led to the development of plant ash glaze, used by artisans for centuries.

Rich in minerals, plant ash combines with quartz and feldspar in clay, forming a glaze under high heat. Its subdued, rustic elegance outshines conventional mineral glazes.

During a demolition, Siming salvaged sixty-year-old wood from an old house. Using this aged timber to make plant ash glaze and cobalt-infused ceramics, they fired a kiln. When opened, the results stunned everyone—unintentional textures, naturally delicate yet earthy.

Thus, the Peacock Glaze was born. The fluid glaze pooled at the base, forming amber-hued layers that cracked like a peacock’s fan. Each piece was unique, its organic patterns exuding a plant-like vitality.

She expanded the series beyond cups to wide-brimmed tea vessels.

▲Peacock Glaze collection

Three years of persistence yielded a work that moved her—and countless tea enthusiasts. Buyers nationwide clamored for her Peacock Glaze cups, with every kiln batch selling out. Repeat customers spread the word, even reaching Taiwan.

Yet success came at a cost. The yield was dismal—just 30% of each batch met her standards. In ceramics, flawed pieces must be destroyed. Joking that it “made her heart bleed,” she smashed subpar works, adhering to tradition.

Only perfection, she believed, deserved a place in the world.

02 Refining the System

Even as Peacock Glaze flew off shelves, Siming slowed down. To her, the work wasn’t yet complete—it lacked a system, a replicable method.

Serendipity was a gift, but it marked the start of deeper research. She experimented with Peacock Glaze on diverse forms—small tea bowls, large vessels, even home decor—seeking harmony.

She explored variations: different plants for ash, kiln atmospheres (oxidizing, reducing), yielding subtle shifts in color and texture—all still Peacock Glaze.

While peers chased livestream sales, she immersed herself in this microcosm. Even her dust allergy faded over years of grinding work.

Just as things stabilized, a turning point came.

▲Studio experiments

In summer 2016, her partner left to pursue other dreams. It was her hardest moment—shouldering the studio alone.

Her family offered another path: a Ph.D. abroad. After nights of reflection, she wrote:

“Some say ceramics is just throwing, trimming, firing—things technology can solve. But we chase primal materials, testing plant ash ratios, failing endlessly. I’ll keep this初心 (initial heart). Though I’m the last one standing, looking back, it’s all worth it.”

She declined the offer, choosing to finish what she’d started. Once decided, she pivoted swiftly.

In the following months, she achieved three feats: building a team, refining her product line, and renovating the studio. Overnight, she matured, steering the studio with market savvy.

She realized ancient formulas needed modern tweaks. Lab analysis of her glazes failed—chemistry couldn’t capture the craft.

A creator, she learned, needed both intuition and rigor.

With her team, she documented every test, stabilizing results. Art became reproducible, transitioning from collectibles to daily wares.

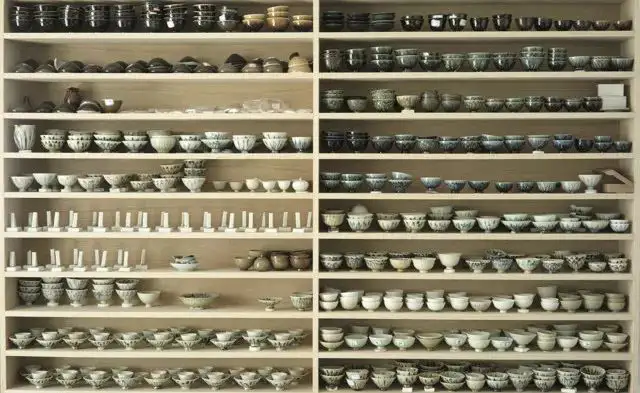

On the studio’s second floor stood a “感性 (emotional) database”—not just test tiles, but a wall of marked Peacock Glaze pieces, each a vivid snapshot of experimentation.

This rigor extended to team management. While many in Jingdezhen treated work like a “permanent vacation,” Siming instilled discipline—fixed hours, no overtime.

She even bought a punch-clock for the studio.

To her, freedom wasn’t chaos. Past all-night kiln marathons gave way to steady, unhurried workflows—avoiding burnout and mood swings.

Method mattered. Kiln prep stretched from 2–3 days to a week, ensuring readiness. Glaze consistency was key. If a piece was uneven or too thin, she’d guide her team to redo it.

From solo artist to leader, from 2017 to 2019, she grew patient and disciplined. Every detail mattered—fixing flaws was the price of true excellence.

03 Exploring Presentation and Expression

When we met again, Siming had painted her studio walls black—a subtle shift reflecting her evolving vision.

Peacock Glaze, though improved, resisted mass production, remaining a line of singular pieces. After years of obsession, she stepped back.

Now, her studio housed a second series: Pure White. Unlike Peacock Glaze, it was a coordinated set—a lidded bowl, pitcher, cups, waste-water jar, tray—priced below a single Peacock cup. As she’d hoped, it was systematic, youthful, scalable.

▲Pure White series

She joked, “I spend two years per glaze, grinding slowly.”

Also plant ash-based, Pure White captured the hues between dawn and dusk—translucent, jade-like.

Her product photos told a story: hands using the pieces, tea settings, light play, life scenes with wine or fruit, even picnics.

Once, a colleague placed a cup by a sweating, overripe lemon. Struck, Siming raced upstairs for her camera, shooting feverishly.

She browsed Instagram, studying how global artists staged their work.

▲Pure White wine cup display

This wasn’t just aesthetics—it was about evoking comfort. Objects, she felt, should stir intuition, bridging screens to spark connection.

She admired photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto’s seascapes—just a horizon line, no waves—yet profoundly moving.

Her Pure White series mirrored this thought. The lidded bowl’s redesign ensured tea poured smoothly, one-handed.

▲Pure White wine cup

Jade-like yet practical, the balance of thinness and heat resistance showcased her precision—from creation to packaging, even imagining the buyer’s unboxing delight.

Darwin believed luck favors the bold. To judge hers, look backward and forward.

The black walls drew eyes to a white ceramic ceiling lamp. Every touch, born of observation, infused her studio and works with life.

▲Pure White / Dharma Form

Siming rarely socialized in Jingdezhen’s ceramic circles. True kindred spirits were scarce. She kept work and life separate, leaving the studio by 7 p.m.

Unlike peers who sought quiet, she lived in a bustling neighborhood—nightly square dances, strollers, fountain crowds. Home meant herbal tea, congee, or bedtime wine. A health-conscious ’90s kid.

She learned in fragments, even dabbling in management books. She pondered modern drinkware, Instagram inspiration.

Her discipline defied the artisan stereotype.

▲Pure White / Colorless / Blue Peacock 2

Post-interview, she left for Shenzhen to meet a visual designer who’d crafted her packaging. She hoped to find a new partner—not necessarily ceramicist, but a creative ally.

The next chapter might hold fresh surprises.