A Father and Son’s Unwavering Journey

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

The Story of Jingdezhen Porcelain Painting: A Father and Son’s Unwavering Journey

Yuan Shiwen specializes in snowscape porcelain painting—a niche art form in Jingdezhen.

He has devoted most of his life to this craft, and today, his works serve as the “textbook” for snowscape porcelain painting in Jingdezhen. The figure working upstairs, meanwhile, has become a source of inspiration for his son, Yuan Zhiyong.

Father and son have carried this tradition forward, their footsteps never pausing.

Yuan Zhiyong still remembers the essay he wrote about his father in fifth grade. That year, his father, Yuan Shiwen, had just become the director of the Art Porcelain Factory. To him, his father was a hero—except this hero wielded a paintbrush instead of a sword.

Yuan Shiwen paints snowscapes on porcelain, a rare technique in Jingdezhen that combines painting with craftsmanship. The style was pioneered during the Republic of China era by He Xuren of the “Pearl Mountain Eight Friends” and later refined by his disciple Yu Wenxiang. As a descendant of Wang Yeting, another member of the Pearl Mountain Eight Friends, Yuan Shiwen initially studied the Wang School’s blue-green landscapes before receiving guidance from Yu Wenxiang, the “Snowscape King,” mastering an impeccable technique.

His father was deeply responsible, never letting his family suffer. Even as factory director, he tirelessly took on commissions, both to support the household and hone his skills. Late at night, when Yuan Zhiyong got up to use the bathroom, the first floor would be silent except for the whirring of a single oscillating fan. Upstairs, however, a light would still be on, accompanied by faint rustling sounds—his father painting in the attic, careful not to disturb the family. By dawn, he would already be gone again.

Later, as he grew older, Yuan Zhiyong set up his own studio downstairs.

01 Learning to Paint: Strictness Has Its Merits

Yuan Shiwen began painting at nine. The eldest of five children, he started working early to ease his parents’ burden. While other children played after finishing homework, he painted. “What’s there to play with? Asking for a beating?” he recalls.

Wang Yeting was his great-uncle, so the family practiced the Wang School’s landscape style. His father was strict. “Back then, I painted at home in winter without heating. My hands would turn red from the cold, and if he saw me slacking, he’d whip me until I bled,” he says.

Then he laughs. “But being strict was good. My solid foundation owes a lot to that discipline.”

At the time, the family lived near the Imperial Kiln in Xiaosu Alley. Yuan Shiwen would sit outside under a makeshift awning to paint. Yu Wenxiang lived just a hundred meters deeper into the alley. Noticing the boy’s dedication, Yu asked, “Want to learn snowscapes?”

“I had no idea who he was at first,” Yuan Shiwen admits. “Later, I learned he was He Xuren’s star pupil—the undisputed ‘Snowscape King’ of the Art Porcelain Factory’s design studio.”

Yu Wenxiang was unassuming but groundbreaking. Trained by He Xuren, he mastered snowscapes while daring to break conventions. In his Treading Snow in Search of Plums, he abandoned the popular segmented composition for a “high-distance” perspective, drawing the viewer’s gaze deeper into the scene.

Thus began Yuan Shiwen’s dual apprenticeship: Wang School landscapes from his father, He School snowscapes from Yu Wenxiang—a dual artistic nourishment.

In 1962, his ailing mother secured him a job at the Art Porcelain Factory. At 16, Yuan Shiwen both colored and painted. His speed and diligence earned him triple the average wage. But two years later, during workforce cuts, he transferred to the Yuejin Porcelain Factory’s design studio. By year five, he was promoted to workshop chief, and by 30, deputy director.

“When I became director, my father was quietly proud,” Yuan Shiwen recalls. “He was ill then. When people told him, ‘Your son’s the director now,’ he just smiled. He never showed much emotion.” To Yuan Shiwen, his father was a silent but pivotal figure—a man who, like him, had endured harsh training under Wang Yeting as a child. Seeing his son master the Wang School and achieve social standing brought hidden joy.

02 Craft Demands Unending Practice

In the 1970s, the Arts and Crafts Factory needed designers and recruited Yuan Shiwen. To him, those were the most hopeful days—skill commanded respect and ensured a good life for his family.

“Back then, we had no AC, just one floor fan for sleeping. In summer, I’d paint through the heat, wiping myself with a wet cloth. My family slept downstairs, while I worked upstairs. Once, my son woke at night and saw the light on. The next day, I’d be off on a trip, sleeping on newspapers spread on the floor.”

Many say snowscapes risk monotony. Unlike blue-green landscapes depicting all seasons, snowscapes capture only winter and early spring. The core challenge is using brushwork to convey snow’s depth, texture, and chill. The monochrome palette must also differentiate still snow, drifts, and blizzards.

Porcelain adds another layer of difficulty. He Xuren solved this by adapting his classical Chinese painting training (rooted in Song and Yuan dynasty studies) to create “snowscape ink painting”—using ink for outlines and overglaze colors like famille rose and glass white for fills.

During this period, Yuan Shiwen refined his craft further, merging the Wang School’s landscapes with snowscapes while emphasizing diverse, logical compositions.

Snow lacks color but reflects its surroundings.

▲ Father and son sketching outdoors

Yuan Shiwen often sketched outdoors, filling a blue plastic notebook with scenes. He also archived nature documentaries, music videos, and films—any footage of landscapes—building a categorized “library” in his studio.

His snowscapes gained dynamism: sunny snow tinged blue, dusk snow glowing red, stormy snow ominous. Snow-draped objects shifted visually—sharp edges softened, roads blurred, houses shrank. Skies and streams darkened; snow gleamed translucent.

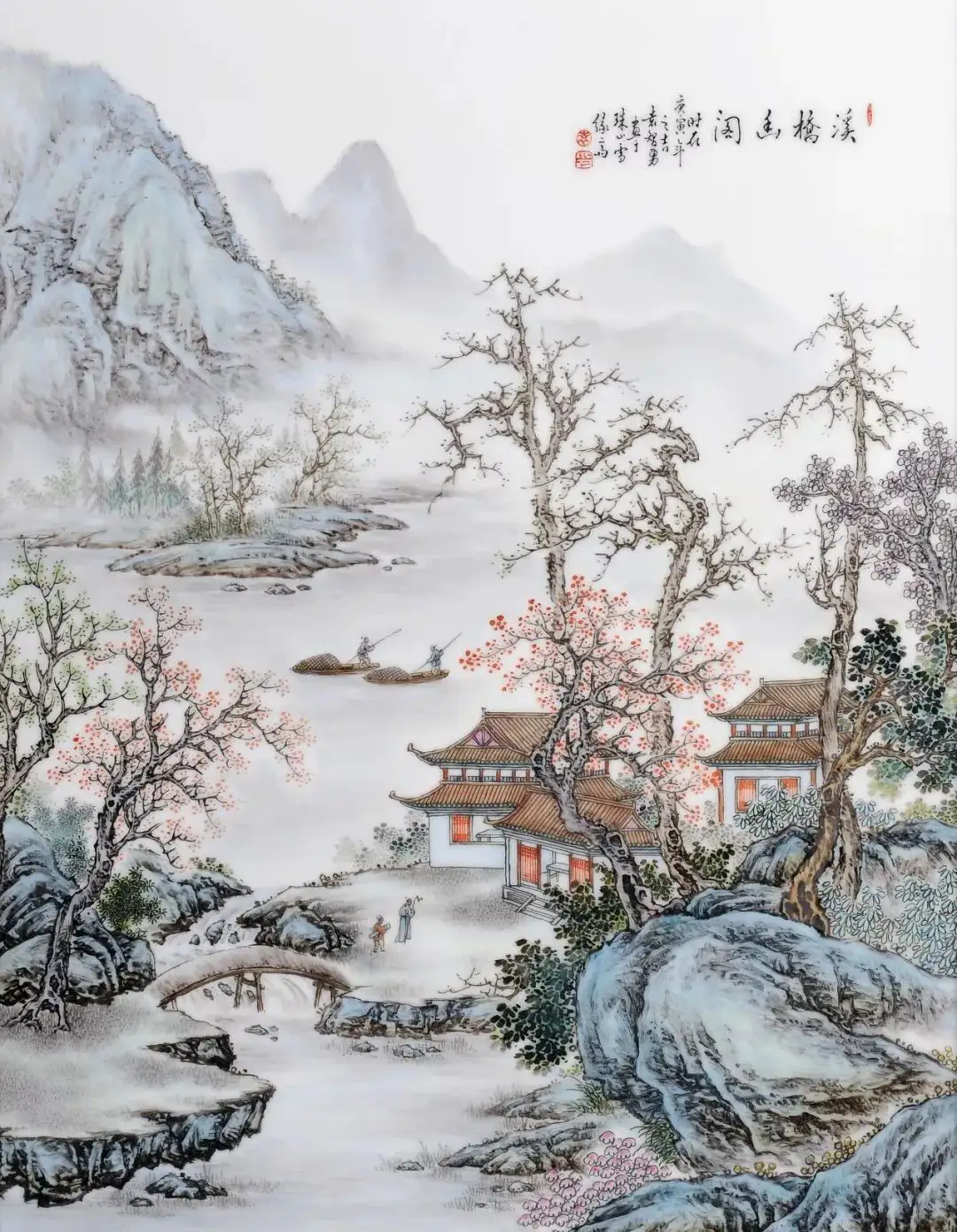

▲ Yuan Shiwen’s works

He also loved depicting small human figures in snow, a Wang School hallmark. Travelers leaning on staffs, scholars at desks, friends meeting on paths—each had distinct expressions. Farmhouses nestled in valleys; distant pagodas hinted at monks’ presence. Viewers and subjects seemed to lock gazes, the frozen landscape becoming a portal to an “ideal life.”

“I supported eight people back then: three kids, two grandmothers, two younger brothers, and my wife, who didn’t have steady work.” Like winter’s temporary blanket, hardship passed as long as resilience remained.

“My children never knew such struggles,” he says, eyes crinkling with a smile.

03 Imitation: A Double-Edged Sword

Unlike his father’s strict upbringing, Yuan Zhiyong learned in a relaxed environment.

The family wasn’t wealthy, but society was simpler. Their combined living-dining room hosted friends and colleagues for meals and chats. Neighbors were close-knit—”grabbing a bowl to share dishes here, rice there.” Yuan Zhiyong recalls those times fondly.

Surrounded by art, he often copied adults’ drawings with chalk on the floor.

Noticing this, Yuan Shiwen tossed him a copy of the Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual.

Yuan Zhiyong thrived on his father’s “mysterious encouragement.” “Once, he bought a watermelon for the family but told me, ‘This is just for you.’ Kids thrive on praise—it gave me energy.”

With Wang Yeting’s original sketches at home and his father’s coaching, Yuan Zhiyong progressed quickly. People praised him: “Wow, this looks just like Wang Yeting’s work!”

▲ Yuan Zhiyong’s works

At first, he was flattered. “Of course it looked like his—I copied directly. As a descendant, I had access others didn’t.” But over time, he questioned it. “Even if I outdid his imitation, it wouldn’t be mine. I remember a Chaplin impersonation contest—Chaplin himself couldn’t have won.”

He sought change, but early attempts to diverge from tradition met resistance. “My early works were hyper-detailed, emphasizing labor-intensive precision. When I tried shifting styles, people disapproved. I wasn’t anxious—just unsure if I was right or wrong.”

Landscapes may seem similar, but each artist’s approach differs. For rocks, Wang Yeting used “folded ribbon” strokes with some “hemp fiber” texture; his daughter Wang Guiying preferred “axe-cut” and “hemp fiber”; later generations used “chaotic hemp.” The variations reflect the artist’s mind, not the scenery. Mere replication is mediocrity.

“My innovations might not succeed, but they’re true to me,” Yuan Zhiyong says. He also studied sketching, oil painting, and watercolors to broaden his skills.

04 That Timeless Atmosphere

Still Missed Today

▲ Yuan Shiwen tending his vegetable garden

The two now live in an old neighborhood. Jingdezhen summers are scorching; by late afternoon, the asphalt radiates heat. Yuan Shiwen often strolls from home, hands clasped behind his back, crossing the street to a small supermarket and adjacent tea shop where neighbors and acquaintances gather.

He cherishes these chats with old friends—teachers, business owners, ordinary folks—all mingling across social lines. It reminds him of younger days when no one locked their doors at night.

“Now, houses are bigger, cars everywhere. To meet someone, you have to travel far.”

This nostalgia echoes both father and son’s shared sentiment—like golden sand settled at the bottom of time’s river, offering enduring nourishment.

Yuan Shiwen often visits his son’s second-floor studio. Sometimes they disagree. “He pulls rank as a father,” Yuan Zhiyong jokes, calling family to vent—though he usually concedes his father’s points.

“His work’s still ‘green,'” Yuan Shiwen concludes.

Yuan Zhiyong protests, “Say ‘young’ instead.”

Yuan Shiwen bursts into laughter. He doesn’t feel old either. He rises at 6:30 a.m., exercises with a soft ball or treadmill, tends his garden for an hour or two, and paints for three more. His focus remains razor-sharp. “When I paint, I’m meticulous. Once immersed, I break through creative blocks fast.”

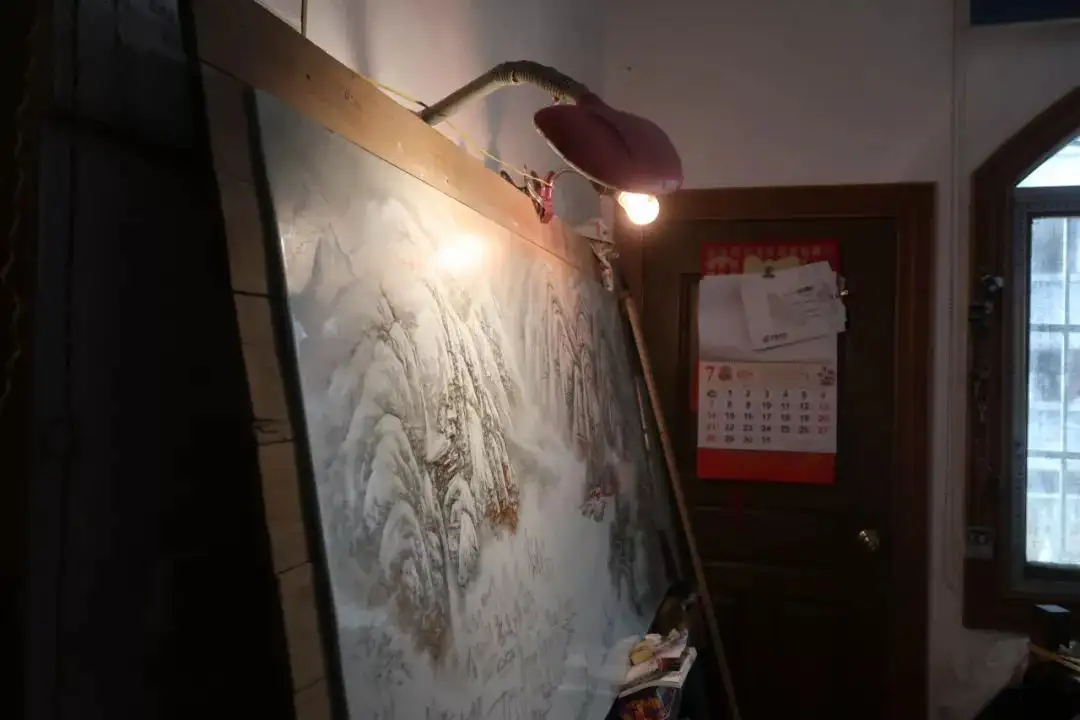

His third-floor studio houses a massive easel for three-meter porcelain panels, bearing his sketched outlines. Sponges, scrapers, and other tools sit nearby. His “library” fills white plastic bins with books and CDs—from 60s-70s films to modern health exercises—his virtual trove of landscapes.

▲ Yuan Shiwen’s collections

A Sony tape deck and full stereo system—his splurge from years ago—pumps out disco beats. Multicolored lights swirl across the ceiling like a kaleidoscope, the pulsating rhythms unleashing raw, joyful energy.

“I listen to this while painting. It’s invigorating!” he shouts over the music.

The dance tracks play on. So does youth.