Smog: The Path to Finding Personal Style is Slow and Endless

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

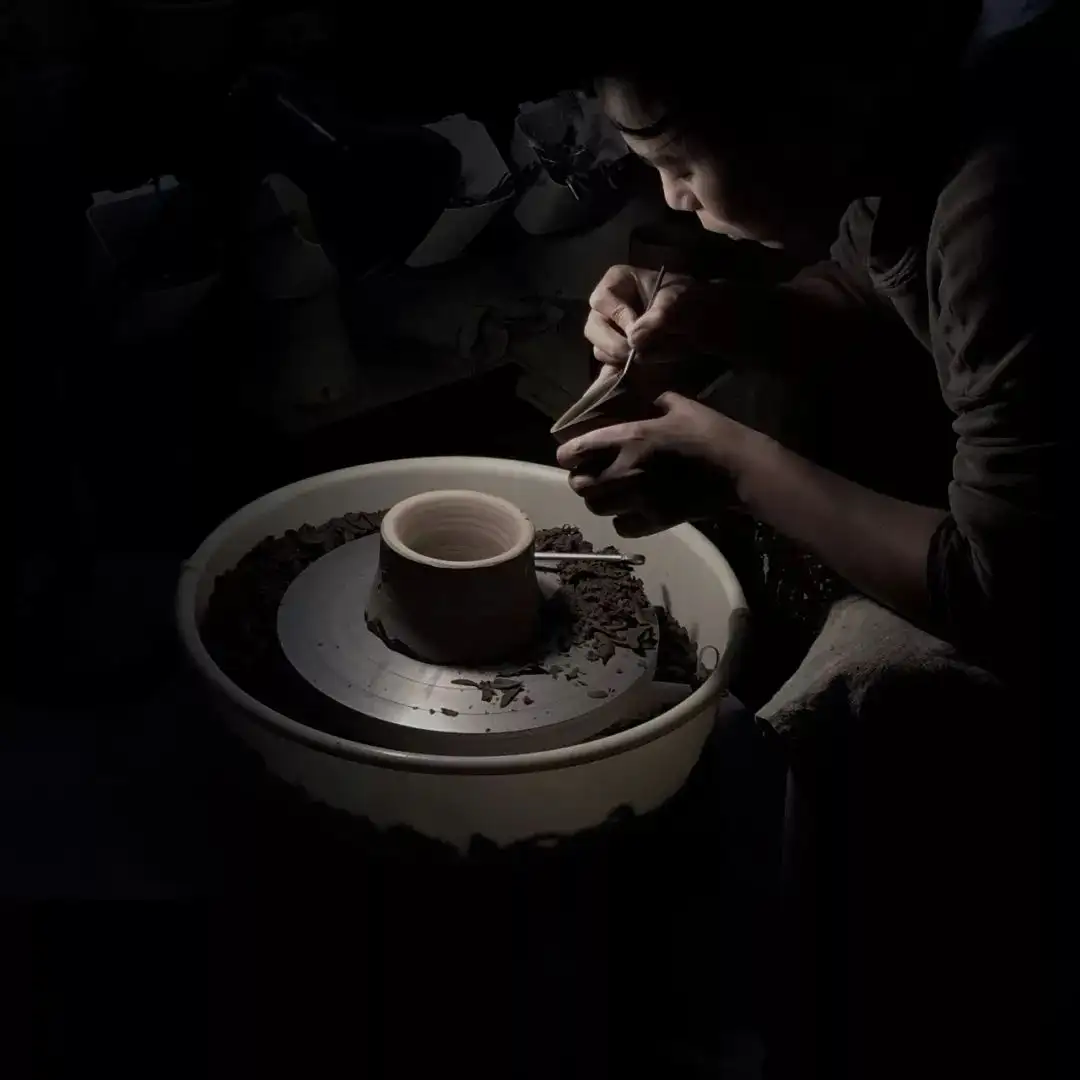

Zhu Zhiyuan’s studio is located in a village near the Ceramic Institute. Walking along the roadside path, it takes only a few minutes to reach this “rural villa.” Pushing open the door to the second-floor studio, slow music fills the room, and the first to greet visitors is not him but his cat.

Apart from his ceramic sculptures, the most visible things in the room are bottles of alcohol. He’s not a heavy drinker, but creativity requires inspiration, and sustaining creativity demands infusing more energy into life.

“My works are the best interpretation of myself—they are the materialization of my life, a microcosm of my thoughts.”

Utensils are part of life, and life is the source of inspiration.

Flowing water, leaping flames, drifting smoke—all exist within the vessels, materializations of my thoughts and expressions of my inner self. Self-awareness is nothing more than a process from vagueness to gradual clarity. So these expressions are no longer just about venting emotions; they can be much more.

But this isn’t important.

One cannot go from ignorance to enlightenment in just a tenth of their life—this is something that will never be fully achieved. So, I’m happy to spend time on these things, and I dislike the idea that everything must have value or meaning.

They are just fragments of my wasted life.

If wind and water erode the land to form canyons and mountains, then “Smog” can be understood as the erosion of thought upon material—slow, winding, but steadfast.

—Smog

“Smog” is not just an artistic name; it’s also the name of Zhu Zhiyuan’s studio. But beyond the studio, fans of One Piece will recognize Smog as a character from the series. He is a former Navy captain with silver short hair, wearing a large coat with the word “Justice” on the back, a pair of goggles around his neck, and the ability to turn his entire body into smoke.

In 2009, Zhu Zhiyuan arrived in Jingdezhen with a backpack to study ceramic art and design, but neither the school nor the city matched his expectations.

“When I came to Jingdezhen, the city was shrouded in a conservative atmosphere—it felt oppressive. Everywhere I looked, there were ‘masterpieces’ of porcelain, but innovation was rare.”

01 If There’s No Opportunity to Learn, Go Find It

Although his initial impression of Jingdezhen wasn’t great, he quickly found his direction. In his freshman year, he rented a studio in Xianghu with three ceramic art majors and two sculpture majors.

The cost of starting a business in Jingdezhen was incredibly low—a 300-square-meter studio cost only 6,000 yuan a year in rent.

With their own studio, the group pooled money to buy pottery wheels, electric kilns, and other ceramic equipment. But even with the tools ready, the school hadn’t started practical ceramics classes yet. Learning, however, is a personal responsibility, so he began experimenting on his own. At the same time, he started learning sculpture with friends.

There was an unused pottery wheel in the studio, so they bought a ton of clay, but none of them knew how to throw pottery.

During the summer vacation of his sophomore year, with little interest in going home, he decided to stay and learn pottery throwing. He went to Laochang, where many Jingdezhen workshops were located—these were the living essence of Jingdezhen and the best teachers, showcasing the pinnacle of local craftsmanship.

The craftsmen there threw pottery with a “wild” style, their skills honed through years of experience. Zhu Zhiyuan watched them closely, observing their techniques, the rhythm of their movements. He would watch, return to the studio to practice, and if something felt off, he’d go back to observe again. He repeated this process relentlessly throughout the summer.

By the time his classmates returned from vacation, he had already mastered pottery throwing.

In his junior year, when the teacher started pottery-throwing classes, Zhu Zhiyuan jokingly asked if he could skip them since he already knew how. The teacher challenged him to throw a 20-centimeter straight cylinder, so Zhu Zhiyuan stepped up and threw a 30-centimeter one. Fortunately, the teacher was open-minded and didn’t restrict him further.

So during college, he spent most of his time in the studio, teaching himself and conducting his own research.

At the time, the Ceramic Institute didn’t have a public kiln for firing works, so he hired an unlicensed taxi to take his pieces to a public kiln at the Sculpture Imperial Kiln. Half of them broke on the way because the roads were terrible—just a little shaking was enough to shatter them.

Zhu Zhiyuan said there wasn’t a great environment for practice back then, but if you truly wanted to learn and master something, the school couldn’t provide it—you had to explore and research on your own.

02 Anxiety and Growth: The Birth of a Personal Style

Gradually, the ceramic art scene in Jingdezhen began to change. The arrival of Lety brought international resident ceramic artists, and the Lety Market, after several years of germination, began to mature, giving young people hope.

The improving environment made more young people realize that staying in Jingdezhen after graduation was feasible.

Under the leadership of Zheng Yi, founder of Lety Ceramics, more interesting young people gathered in Jingdezhen, forming a shared community. They often exchanged ideas, becoming a new force injecting vitality into the city.

After graduation, the pressures of life forced Zhu Zhiyuan to consider his livelihood. Although his ceramic skills were solid, he felt conflicted.

“I didn’t want to compromise by making functional ware.”

At the time, he was more eager to express his thoughts and emotions through sculpture, but the market for large pieces was tiny. The meager income couldn’t sustain a decent life, so he reluctantly left Jingdezhen for a while. He went to a sculpture factory to work on large-scale sculpture projects. These projects were grueling, often completed in just ten days, but the pay was good.

From early 2014 to 2015, the market began to improve, and he started to change his perspective. Making functional ware wasn’t as limiting as he’d thought—the medium was just a vehicle. As long as he infused his own way of thinking into the work and took it seriously, the results would naturally be outstanding.

He experimented with making many oddly shaped teapots—some large, some small, each one unique. Even though the works weren’t yet mature, the market gave him a boost of confidence at this critical moment.

At the time, his teapots sold for over 200 yuan each, and every time he set up a stall at the Lety Market, they sold out. His monthly sales reached over 40,000 yuan, which excited him. He realized that people didn’t reject his style—at least some could accept it. The early affirmation of his teaware strengthened his resolve to stay true to himself.

As his style began to emerge, it garnered both praise and criticism. Some felt his teapots were impractical, and his ideas were still too superficial.

With newfound confidence, he began refining his style further.

Starting from the essence of ceramics, he studied clay, glaze, and firing temperatures. He bought different types of clay, experimented with adjustments, and tested strong versus weak reduction firing. At the same time, on his teacher’s recommendation, he went to Yixing to learn techniques for making tea ware, gradually considering the user’s experience.

“When you want to express certain ideas, you must rely on yourself to deeply understand and master the material. I’ve never believed in leaving the results to fate—who are you kidding? If a work isn’t complete, it’s because you haven’t mastered it enough.”

By 2016, friends remarked that Zhu Zhiyuan’s growth was visibly rapid, and his style began to stabilize. Everything seemed to be moving in a positive direction.

Elements of sci-fi, metallic textures, and dynamic expressions gradually appeared in his works.

03 The Lonely Life Enthusiast

Walking into Zhu Zhiyuan’s studio, it’s immediately clear that he’s a life enthusiast. He enjoys listening to post-rock while working, cooks lavish dinners for himself paired with his collection of wines, keeps two cats, and sports a distinctive bohemian wave perm.

But he’s always been a bit lonely—not because he’s single, but because he cherishes his independence.

The end of 2016 marked a special turning point in Zhu Zhiyuan’s life. By then, he had finally solved his financial problems. His tea ware was in high demand, his income was stable, and he could discuss professional and conceptual ideas with close friends.

But one day, he suddenly felt that if he continued like this, he’d be ruined.

In his friends’ eyes, he saw a successful version of himself—it seemed like he could just keep going down this path.

But, “Am I still myself? Am I being dragged along by the market? The superficiality of my thoughts made me seek out like-minded people for security. Is this good?”

After repeatedly questioning himself, he fell into a period of self-isolation. Finally, unable to find an outlet for his emotions, he chose to leave this environment—from Jingdezhen to Beijing, and then to Mohe.

Mohe was freezing. He’d decided to go on a whim and only bought a down jacket, completely unprepared. “I felt like I was going to freeze to death—all I wanted was to go home and sit by the stove.” Yet in this extreme environment, he realized what he truly wanted: to return to himself. “I just like black. I like metallic textures, matte finishes. I only care about myself.”

He had to hold onto these personal expressions because only then would his works truly reflect him.

To him, black is the richest form of expression—it’s not just the color it appears to be. He began formulating black glazes, from deep brown to large-grained black, matte black, fine-grained black, fluorescent black, and finally pure black.

His patterns became more stylized—comics, architecture, ethnic minority cultures, sci-fi—all elements he loved. Compared to flat lines, spirals had more tension, capturing attention. He began finding a more precise way to express this in his forms.

He often went to the river to observe small whirlpools and watched leaping flames in bonfires.

“I hope that when you see my work, it feels like a knife pressed against your forehead—that kind of feeling of oppression. It’s impactful, something you can feel immediately.”

For the next two years, he continued working on his black series, exploring more forms and styles—tea ware, incense burners, wine vessels, and highly personal sculptures.

But he was also ambitious. He didn’t want to be defined solely by black or spiral patterns. He wanted to create works with tension and weight—as heavy as mountains, as lively as flames.

He remained in a state of self-contradiction.

On one hand, he faced life’s pressures—he’d bought a house and had monthly mortgage payments. On the other, he desired change and wanted to keep pushing his boundaries. Many artists bravely abandon the styles that made them famous to pioneer new ones. But he felt he wasn’t yet capable of that. His expressions could still be more complete, and he hadn’t yet gained widespread recognition. Everything was just beginning.

▲ Solaris Series—Memories of Fire

The path to finding one’s style is an adventure in another dimension—a journey of dreams and passion.

Perhaps, as he wrote at the beginning, none of this has any real meaning. It’s just a beautiful waste of time, belonging entirely to him.