Li Yun: Mastering Antique Porcelain is Like Cultivating Martial Arts in the Jianghu

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Li Yun: Mastering Antique Porcelain is Like Cultivating Martial Arts in the Jianghu

Li Yun was born in Jingdezhen and has loved painting since childhood. After graduating from high school, he joined the Folk Special Art Research Institute under the Science and Technology Commission, where he learned ceramic painting from veteran artisans. In the late 1980s, he established his own studio, focusing on ceramic sculpture. In the early 1990s, he shifted to the production and replication of antique porcelain glazes. Over the past thirty years, he has restored many lost techniques and varieties, presenting the pinnacle of Jingdezhen’s ceramic craftsmanship through his antique porcelain works.

To outsiders, Jingdezhen’s antique porcelain circle seems somewhat mysterious. Fanjiajing is the sales hub for antique porcelain in Jingdezhen, but ordinary visitors usually only encounter mid-to-low-end replicas. The true masters are elusive, scattered in hidden corners of the city. They don’t hang signs or openly operate businesses—without a guide, it’s impossible to find them.

Yet, once you enter the circle, you realize it’s not large. Reputation and skill are everything here. The craft of replicating ancient artifacts is highly technical, and the true masters are also experts in ancient ceramics.

As for reputation, the antique porcelain circle has its own rules. Historically, Chinese ceramics have always involved later generations replicating earlier works. The ancestors set the standard: antique replication is about pursuing perfection in craftsmanship. These artisans don’t engage in forgery—they openly state that their works are replicas. What happens afterward is none of their concern. Because their works are high-value art, buyers prefer discretion, so they produce limited quantities and avoid public attention.

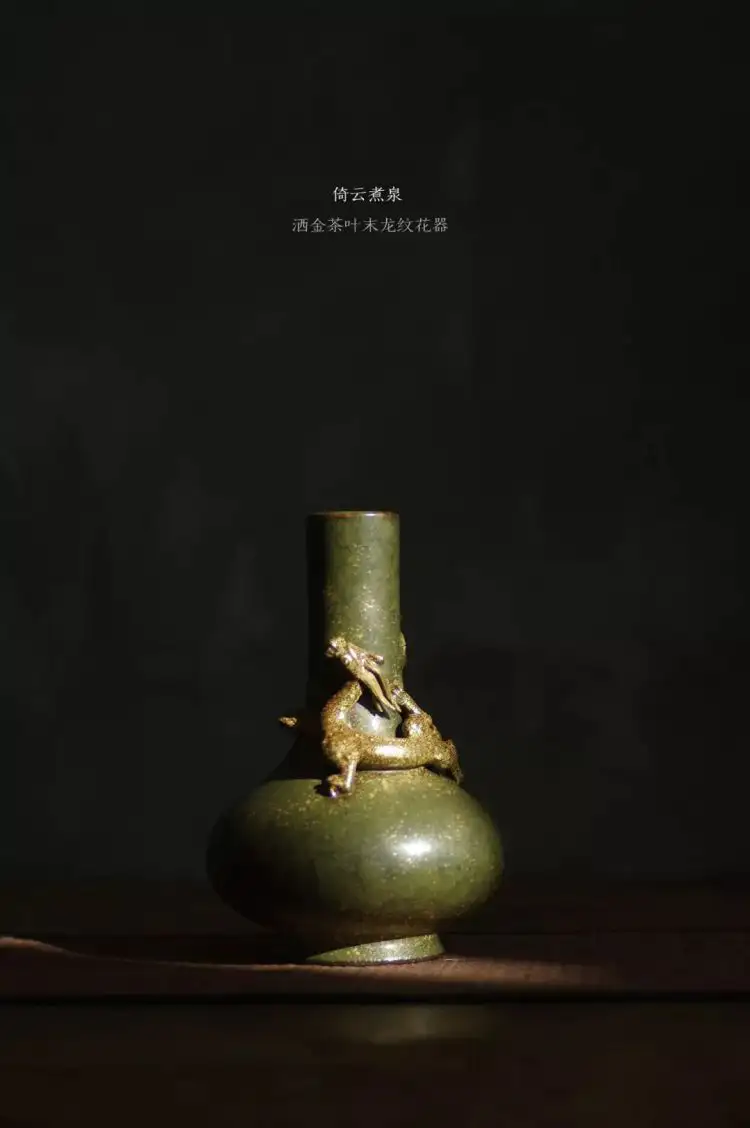

Li Yun is highly respected in the circle for both his skill and reputation. Low-key and amiable, he often wears a black T-shirt. His expertise lies in Qing Dynasty ceramics, particularly exquisite carved porcelain and monochrome glazes, with tea-dust glaze being his specialty.

Regardless of age, everyone in the circle calls him “Second Brother.” Wherever he goes, people offer him drinks or insist on paying for meals. He responds politely but avoids excessive socializing. At the dinner table, he steers clear of technical discussions or comparisons—he’s simply a food enthusiast who becomes talkative when the topic turns to cuisine.

In Li Yun’s eyes, antique porcelain replication isn’t as mystical as people think. It’s like cultivating martial arts in the Jianghu—progressing step by step, studying extensively, experimenting tirelessly, relying on insight and diligence. When he finally restores a lost technique, the excitement is unparalleled.

It’s this very excitement that has sustained him through the long years.

01 Outside the Family, Everything Depends on Yourself

Li Yun loved painting in his youth. In 1984, after graduating from high school, he worked at his father’s plastics factory. But the sight of the massive machines frustrated him. Fortunately, his uncle was involved in ceramics, so he left the factory and joined the Folk Special Art Research Institute on his uncle’s recommendation.

At the time, the institute housed fifty or sixty retired ceramic artisans with nowhere else to go, each possessing unique skills. Li Yun apprenticed under them, learning blue-and-white and famille-rose painting. But he found famille-rose painting too monotonous—copying the same traditional patterns day after day didn’t satisfy him.

The artisans at the institute specialized in different areas—some in shaping, others in carving. So while painting, Li Yun also learned other ceramic techniques from them. Since there were no conflicts of interest, the learning environment was excellent. The artisans shared everything they knew, and he quickly mastered carving and other skills.

After two years of training, he left in 1989.

In Jingdezhen, many make a living from ceramics. “Who doesn’t use porcelain bowls?” Back then, he entered the industry with this mindset, seeing it as a viable livelihood. Early on, he painted porcelain and carved plain ware—tasks he could do alone behind closed doors, with ready buyers for his work.

But while carving, he noticed that intricate details could be lost if the glaze wasn’t applied correctly. In those days, Jingdezhen wasn’t as open as it is now, and colored glazes were hard to come by. The formulas were closely guarded by a few technicians and families, inaccessible without connections.

He tried buying pre-made glazes but found that even with the technician’s formula, his pieces still failed. He didn’t know the right glaze thickness, firing temperature, kiln atmosphere, or whether to maintain heat during the process.

Li Yun dislikes relying on others. Faced with these challenges, he delved into glaze research. At the time, the field was largely unexplored. Starting with transparent glaze, he gradually studied red, green, and blue glazes. The more he learned, the more he marveled at the depth of traditional colored glazes.

“At first, I had grand ambitions—like mastering the best sacrificial red glaze.”

The process of experimentation, verification, and refinement was grueling yet thrilling. Gradually, his mindset shifted from seeing it as a livelihood to a genuine passion.

By chance, he met Chen Yelin, a pivotal figure in his life. Chen had resigned from the Ceramic Institute to start a private ceramic company, becoming one of the earliest entrepreneurs in the field. Impressed by Li Yun’s talent, Chen offered him a workshop in Fanjiajing—originally a warehouse—to produce antique porcelain.

They agreed to split any profits; if there were none, so be it. This opportunity brought Li Yun to Fanjiajing, where he hung a sign for an “Ancient Ceramics Research Institute” and began his studies.

From 1989 to 1999, Li Yun experienced rapid growth, coinciding with Fanjiajing’s transformation. When he first arrived, Fanjiajing was known for vegetable farming and tofu production. In the 1990s, a wave of “antique fever” swept regions like Southeast Asia, attracting buyers from Hong Kong and Singapore.

The wave of reforms and market demand dramatically changed life in Fanjiajing. Crowds flocked to open ceramic workshops, and antique porcelain was sold in the People’s Square, about a kilometer north.

Some buyers sought Li Yun out, bringing damaged pieces and asking him to recreate them. This pushed him to keep learning. Li Yun has a researcher’s spirit—he’s willing to invest time and has his own methods.

“Over the years, I’ve learned to do everything myself. When I asked others to prepare glazes, the results weren’t what I wanted. So I took matters into my own hands. I’ve been on my own for a long time—I don’t like relying on external help. Since leaving home, I’ve been self-made.”

02 Antique Replication is a Profound Technical Craft

What exactly does antique porcelain replication entail? Some in the industry compare it to the dedication of scientists developing the atomic bomb.

The inheritance of each glaze color has faced multiple catastrophic interruptions.

For example, during the Yongle and Xuande periods of the Ming Dynasty, techniques reached unprecedented heights. The “fresh red” glaze, also called “drunken red” or “gemstone red,” was renowned for its rich hue and became a rare treasure. However, due to the difficulty of high-temperature copper-red glaze firing and strict material requirements, production ceased by the mid-Ming Dynasty.

By the Kangxi era of the Qing Dynasty, Jingdezhen’s kilns flourished again. After painstaking efforts, high-temperature red-glazed porcelain was successfully revived, with “bean-red” porcelain standing out as the finest.

Each historical period had its own peak glaze colors. Antique replicators aim to reproduce these pinnacle glazes and forms. But many original formulas are lost, and during repeated trials, factors like raw material ratios, firing atmosphere, temperature, and kiln positioning all affect the glaze’s final color.

Even if the process is documented, the real path must be walked again. Li Yun’s work involves retracing history’s most challenging paths.

Back then, unmarried and unafraid of hard work, he immersed himself completely.

Li Yun never acts unprepared. To excel in antique replication, one must thoroughly understand ancient works—studying their glazes, shapes, textures, and possible firing methods. Whenever possible, he examines originals in museums.

During preliminary research, he gathers as much material as possible. Historical literature was easier to find back then—he frequented Xinhua Bookstore for papers and books on ancient ceramics. For instance, when researching copper-red glaze, he collected dozens of related domestic and foreign texts, including studies on German copper-red glass.

At the time, there were two schools of thought on copper-red glaze: one advocated colloidal coloring, the other ionic coloring. Some even suggested adding carbon. He used these references to conduct tests.

Colored glazes are essentially explorations of material technology. By mixing metal oxides and natural minerals into the glaze and firing the porcelain at high temperatures, different colors emerge.

The ancients relied on experiential knowledge; today’s artisans depend on thought and rigorous science.

Much of this exploration requires long-term accumulation. For example, Li Yun once traveled to all the mining sites around Jingdezhen, marking and recording the ores. With transportation being inconvenient, he rented a taxi for days at a time, visiting historical mines to collect samples for analysis and comparison with ancient texts.

For nearby sites like Sanbao Village, he rode a bicycle, covering thirty kilometers a day to gather stones from each pit.

His mineral records helped him understand raw material conditions. For antique replicators, firsthand information is essential.

Even with all the data, replicating an identical glaze color requires overcoming many hurdles. Li Yun says he rarely takes detours, but some paths take days, others years, and some span entire lifetimes.

For instance, when he first tried replicating the “Ru Jun” glaze—a low-temperature glaze from the Yongzheng era that mimics Jun ware, with its flowing blue-purple hues—he failed repeatedly. He set it aside, only to have a breakthrough over a decade later.

“I want to restore lost ancient techniques, hoping others will carry them forward. Many talk about innovation, but there’s a boundary between old and new. Without the old, there can be no new.”

03 Gazing at the Vast Starry Sky of the Ancients

Jingdezhen’s antique porcelain industry is no monster—it represents the highest level of traditional ceramic craftsmanship. Each era’s masterpieces boast unparalleled glaze beauty and form. Replicating them one-to-one is incredibly difficult.

For example, the two tea-dust glaze washers on Li Yun’s tea table look similar to laymen but differ by two dynasties in the eyes of experts. The “eel-yellow” hue belongs to the Yongzheng period, while the greenish tint is characteristic of the Qianlong era.

Replicating only roughly and calling it innovation invites disdain in the industry. Antique replication demands perfection.

Li Yun holds deep respect for those bygone works. “They were made by the best craftsmen and teams, sparing no cost or effort. Today, thinking a small kiln can surpass that era is impossible.”

But antique porcelain once circulated only among the wealthy. Li Yun hopes to revive lost techniques in his lifetime, bringing them back into public view and daily life.

Thus, Li Yun transitioned from an antique porcelain artisan to a brand founder. He established his own brand, “Yi Yun Zhu Quan,” to develop ancient-inspired products. He tweaks glazes and corrects flaws, whereas traditional replication insists on copying even the imperfections.

Opening another door in his studio, Li Yun leads us to the production workshop. Along the walls stand seven kilns—electric, gas, dual-use, and even ones that can burn charcoal. These kilns were custom-designed by Li Yun to suit his needs.

As he walks, he inspects freshly fired pieces—some too soft in body, others in glaze. A glance reveals subtle flaws or imperfections that escape most eyes.

The craftsmen work in specialized roles, each handling a specific step. The carving, in particular, is astonishingly detailed, with steady hands at work. Li Yun moves among them, offering succinct guidance.

At his desk, piled high with books on ancient ceramics, he remains hands-on, just as in his youth, still tackling unsolved challenges.

“Extremely serious, extremely focused.” These are the words used by the Yu family of Yi Lin Tang, another antique porcelain studio, to describe “Second Brother.”

The vast starry sky left by the ancients is worth a lifetime of pursuit.